Meditation and Neuroscience: New Wave of Breakthroughs in Research on Meditative Practices

Culture- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Legs in tights, extending from leotards and terminating in pointe shoes, briskly cut through the air. Instructions are called out as the dancers, faces aglow, carry their arms in delicate arcs and place their feet in deliberate motions. Leading the ballet class at a dance studio in Tokyo is a 27-year-old woman whom we will call Murano Kozue. The students would never imagine that their petite teacher was once quite the juvenile delinquent or that she used to suffer from bulimia stemming from emotional imbalance.

That all began to change when she attended a 10-day meditation retreat in Kyoto on the advice of her mother’s friend. Meditation in Japan is generally performed as a Buddhist discipline in pursuit of enlightenment, but this retreat was conducted in a secular setting. The core of the program was silence: Not only were smartphones banned, but participants were also forbidden to talk with one another or even make eye contact. They arose at 4 am and had nothing to eat from noon onward. Until 9 pm each day, they would spend about 10 hours seated on the floor with their legs crossed.

To Murano, this regime felt like torture. Even so, she says, since the training was conducted in the company of other people, it was emotionally easier than being detained one of the solitary rooms at the juvenile classification home. During the 10-day program, she began to take part as a volunteer, doing things like cleaning and cooking for the participants. “At first I assumed the people around me were all just acting nice for show, so I was surprised to find that they were genuinely good people.” And before she knew it, she had gone for months without binge eating.

Meditation’s Role in Suppressing Stress Hormones

It is only in recent years that the effects of meditation, including Zen, on depression and other mental illnesses have been substantiated. Much of the credit goes to molecular biologist Jon Kabat-Zinn of the University of Massachusetts Medical School. A serious practitioner of meditation, Kabat-Zinn developed an eight-week program called Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction by isolating the techniques of meditation from the context of Buddhism. The program opened its doors in 1979 to patients with chronic pain and stress. As of 2011 more than 19,000 participants had completed the program, proving MBSR effective. The worldwide interest that the program generated has contributed to an exponential increase in studies on meditation in the mainstream of neuroscience research over the past decade.

When mindfulness techniques or Zen meditation heighten one’s focus and activate the brain, the functions of the brain’s dorsolateral prefrontal area are amplified. This strengthens the psyche and boosts the immune system, as well as enhancing one’s memory and work efficiency. Those suffering from depression exhibit diminished functions in this area of the brain. Activity in the amygdala—the brain’s center of emotion—increases instead, making patients more prone to secrete the stress hormone, cortisol. Meditation has been shown to shrink the amygdala.

The Changing Adult Brain

In Japan, the heartland of Zen, a rising generation of researchers is endeavoring to unravel the correlation between meditation and the brain, primarily at Kyoto and Waseda Universities.

I visited with Fujino Masahiro, a postdoctoral fellow of the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, currently enrolled at Kyoto University’s Graduate School of Education. He is a frontrunner in neuroscience research on meditation.

“After finishing college, I’d been working at a healthcare company for seven years,” Fujino says, “when I began to feel that I needed to be healthy myself before I could fully contribute to other people’s health.”

It was around that time that he attended a 10-day meditation retreat, where he discovered first-hand how the practice enhanced his well-being. Confronted with a gulf between what he had experienced and public images of meditation, Fujino felt compelled to take action. He resigned from his job and went back to school at Kyoto University, where he applied himself to studying the neuroscience of meditation.

“One reason behind the dramatic progress in meditation research is that the idea of neuroplasticity—that the brain retains mutability even in adulthood—has become widely accepted,” explains Fujino. “Until the 1990s neuroscientists believed that the brain loses its capacity to change once a person reaches adulthood. But with advances in research on brain function measurement using new techniques like functional magnetic resonance imaging, we’ve gradually learned that the adult brain, too, continues to be mutable. And in 2004 Richard Davidson, a leading expert in meditation neuroscience, showed that the adult brain can change through meditation as well.”

Anxiety and Excessive Brain Idling

A key concept in discussing plasticity is the default mode network. When we use our senses or engage in activity, different areas of the brain operate together by forming networks. The DMN comes to the fore when we are not doing anything in particular; it is involved in such idle processes as reminiscing about the past and imagining the future. The brain in default mode is like an idling engine. The time spent in this state is what enables us to organize past events and anticipate future ones. But too much DMN time can lead to melancholy and anxiety, as recent studies have shown.

Fujino is collaborating with Ueda Yoshiyuki, a program-specific assistant professor at Kyoto University’s Kokoro Research Center, using the center’s MRI equipment to determine how different types of meditation affect the brain. They have thus far found that Vipassana, or insight meditation, in which the subject observes minute bodily sensations without responding to or judging them, tends to weaken the correlation between the DMN and those areas of the brain associated with emotions and memory.

Individuals struggling with depression or anxiety tend to ruminate excessively on negative experiences and worries about the future. Reducing the link between the DMN and the brain’s emotional and memory centers makes a person less prone to replaying negative experiences, potentially also freeing the person from anxieties about the future that are projected from those experiences. Fujino is preparing to publish the results of his research in an international journal, hopeful that they may provide clues to achieving a “sense of happiness in the present moment.”

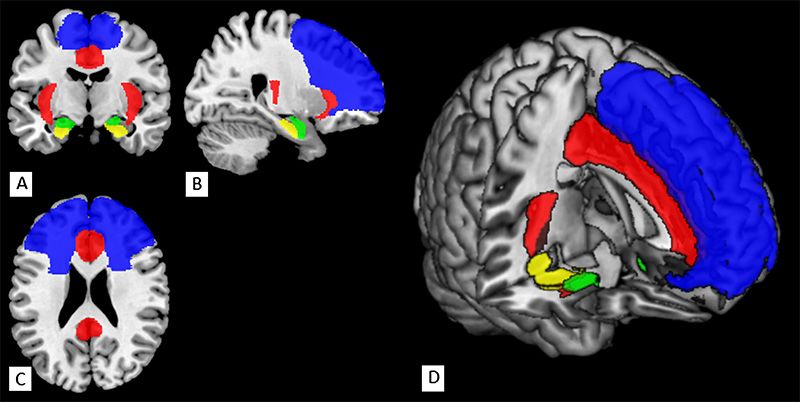

Changes in the brain induced by an eight-week meditation program, such as MBSR. A. coronal section; B. sagittal section; C. transverse section; D. composite view. Blue indicates the prefrontal cortex, associated with the immune system and resilience. Yellow indicates the hippocampus, associated with memory. The upper red region is the cingulate cortex, associated with emotional and impulse control and dealing with conflict. The lateral red regions are the insulae, which integrate bodily sensations and process internal sensations. The green indicates the amygdala, which governs emotions and regulates stress hormone secretion. Meditation training was shown to increase activity in the blue, yellow, and red regions and reduce activity in the green.

Changes in the brain induced by an eight-week meditation program, such as MBSR. A. coronal section; B. sagittal section; C. transverse section; D. composite view. Blue indicates the prefrontal cortex, associated with the immune system and resilience. Yellow indicates the hippocampus, associated with memory. The upper red region is the cingulate cortex, associated with emotional and impulse control and dealing with conflict. The lateral red regions are the insulae, which integrate bodily sensations and process internal sensations. The green indicates the amygdala, which governs emotions and regulates stress hormone secretion. Meditation training was shown to increase activity in the blue, yellow, and red regions and reduce activity in the green.

Source: R. A. Gotink et al, “8-week mindfulness based stress reduction induces brain changes similar to traditional long-term meditation practice–a systematic review.” Brain and Cognition, 108 (2016), 32–41.

Alpha Waves and Mindfulness

Waseda University, meanwhile, is approaching the default mode network and the effects of meditation from a brain wave angle.

In the 1980s and 1990s, alpha waves were all the rage in electroencephalographic research. Alpha waves, which become dominant when a person is in a relaxed state, were believed to be beneficial for health and to improve work efficiency.

The research by Takahashi Tōru of the Waseda University Graduate School of Human Sciences, also a JSPS postdoctoral fellow, runs directly counter to this theory. Takahashi’s hypothesis is that stronger alpha waves inhibit us from noticing subtle sensations and interfere with insight meditation. Conversely, in a state of mindfulness, “alpha waves subside, the senses are heightened, and one becomes keenly aware of one’s connection with the surroundings.”

In the world of sports, a growing legion of athletes are practicing mindfulness to improve performance. Takahashi is working to develop a neurofeedback system for athletes. The idea is to provide real-time feedback to them on the state of the brain during mindfulness or meditation by measuring biosignals and brain waves, helping them to boost their performance and better practice meditation. Achieving the “in the zone” state that athletes and racers sometimes speak of may become a simple matter in the relatively near future.

“Relaxation in the general sense and meditation are different,” notes Associate Professor Nomura Michio of the Kyoto University Graduate School of Education, who advises Fujino. “Relaxing doesn’t relieve brain fatigue; what’s important is to ease excessive idling in the DMN state by engaging in meditation. Meditation is a third state of mind distinct from both tension and relaxation.”

Thanks to the rapid developments in neuroscience, we have learned that what may seem like relaxation—just sitting around doing nothing and paying attention to nothing in particular—is not necessarily good for our mental health. Mindfulness is often seen as being no more than a passing fad. But people may be beginning to realize that there really is something to the third state of mind implied by such words as “Zen,” “meditation,” and “mindfulness.”

(Originally written in Japanese by Koyama Tetsuya and published on April 18, 2017. Photographs by the author unless otherwise stated. Banner photo: © PIXTA.)