“Underground Temple” Safeguards Greater Tokyo from Floods

Culture- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

A Popular Filming Location

Walk down 116 steps from a small hut standing in a corner of a soccer pitch along the Edo River, and you will come upon a cavernous opening 177 meters long, 78 meters wide, and 18 meters high. In it are arrayed 59 concrete columns, each weighing 500 tons. This is the pressure adjusting tank of Tokyo’s Metropolitan Area Outer Underground Discharge Channel. From its solemn, awe-inspiring atmosphere, it has been likened to an “underground temple” and has been attracting visitors from around the world. Located in the city of Kasukabe in Saitama Prefecture north of Tokyo, it is frequently used for photo shoots for fashion magazines and is a well-known location for filming movies, music videos, and TV shows such as tokusatsu (special effects) superhero serial Kamen Rider (Masked Rider).

The templelike atmosphere of the pressure adjusting tank.

The templelike atmosphere of the pressure adjusting tank.

The pressure adjusting tank is part of the Shōwa Drainage Pump Station, which is also home to the Ryūkyūkan underground exploration museum. There, after listening to an explanation about the facilities and viewing the exhibits, visitors can take guided tours down to the floor of the tank. These tours are immensely popular and reservations are hard to secure. Despite being open to the public only on weekdays and one Saturday a month and the possibility of reservations being suddenly cancelled when the facility goes into operation after heavy rainfall or undergoes maintenance or checks, the number of visitors has exceeded 40,000. Many visitors—both young and old—enjoy posing for photos with figures or model weapons used by heroes in the many films and TV episodes shot at the facility.

Upper left: The entrance to the pressure adjusting tank sits in a corner of a soccer pitch. Upper right: The “underground temple” is reached by descending 116 steps. Bottom: Part of the roof is opened to lower maintenance equipment, providing a rare opportunity to see the tank illuminated with natural light.

Upper left: The entrance to the pressure adjusting tank sits in a corner of a soccer pitch. Upper right: The “underground temple” is reached by descending 116 steps. Bottom: Part of the roof is opened to lower maintenance equipment, providing a rare opportunity to see the tank illuminated with natural light.

“People have been awed by the colossal scale of the pressure adjusting tank, and this has increased interest in the actual function of the underground discharge channel,” notes Yabe Takayuki, who works in the local office of the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism’s Kantō Regional Development Bureau. “Participating in the tour and seeing the exhibitions and videos in the Ryūkyūkan not only deepens understanding of the benefits of this system and what it has accomplished but also heightens people’s awareness of disaster prevention when they see how frightening floods can be. That’s why we always try to cooperate with the media in reporting and filming.”

Upper left: Yabe Takayuki of the Metropolitan Outer Floodway Management Office offered a guide of the facility. Upper right: Yabe stands next to a pillar to give an idea of its size. Bottom: The floor is covered with sediment carried in with water just a few steps away from the tourist area, suggesting how frightening floods can be.

Upper left: Yabe Takayuki of the Metropolitan Outer Floodway Management Office offered a guide of the facility. Upper right: Yabe stands next to a pillar to give an idea of its size. Bottom: The floor is covered with sediment carried in with water just a few steps away from the tourist area, suggesting how frightening floods can be.

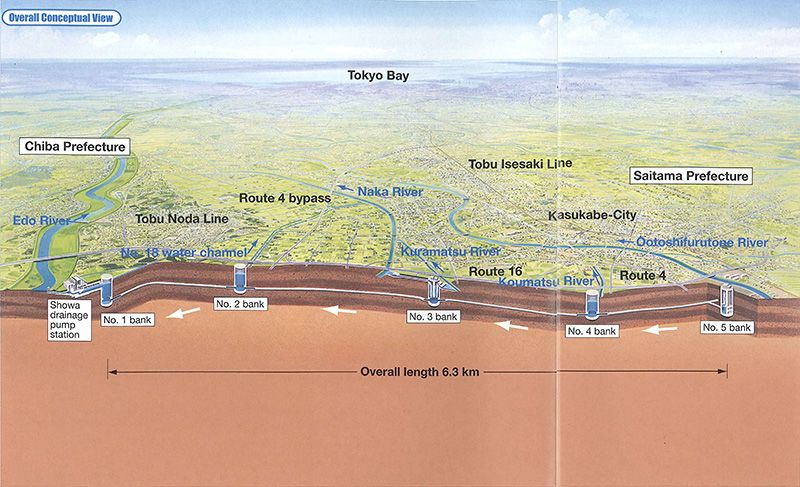

A 6.3-Kilometer Underground River

The discharge channel is located in the city of Kasukabe. It and neighboring municipalities lie in a low plain surrounded by several large rivers—the Tone, Edo, and Arakawa. The area is like the bottom of a bowl, where rainwater accumulates easily. Another waterway flowing through the area is the Naka River, which has a gentle gradient so that water does not flow downstream quickly. It does not take much for the water level in this river to rise, and flood damage is frequent. Moreover, urbanization is spreading from the downstream regions to the middle and upper reaches of these rivers, making it more difficult to create flood control channels above ground. These factors led to the construction of one of the world’s largest underground flood control facilities.

Work began on the discharge channel in March 1993. Some sections went into operation in June 2002, and all sections were in service by June 2006.

The same intersection in Satte, Saitama Prefecture—downstream of the Metropolitan Area Outer Underground Discharge Channel—in July 2000 (left) and October 2004 (right), before and after the Discharge Tunnel was opened. They show the flood situation after similar amounts of rainfall. (Photo provided by the Edogawa River Office, Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport, and Tourism.)

The same intersection in Satte, Saitama Prefecture—downstream of the Metropolitan Area Outer Underground Discharge Channel—in July 2000 (left) and October 2004 (right), before and after the Discharge Tunnel was opened. They show the flood situation after similar amounts of rainfall. (Photo provided by the Edogawa River Office, Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport, and Tourism.)

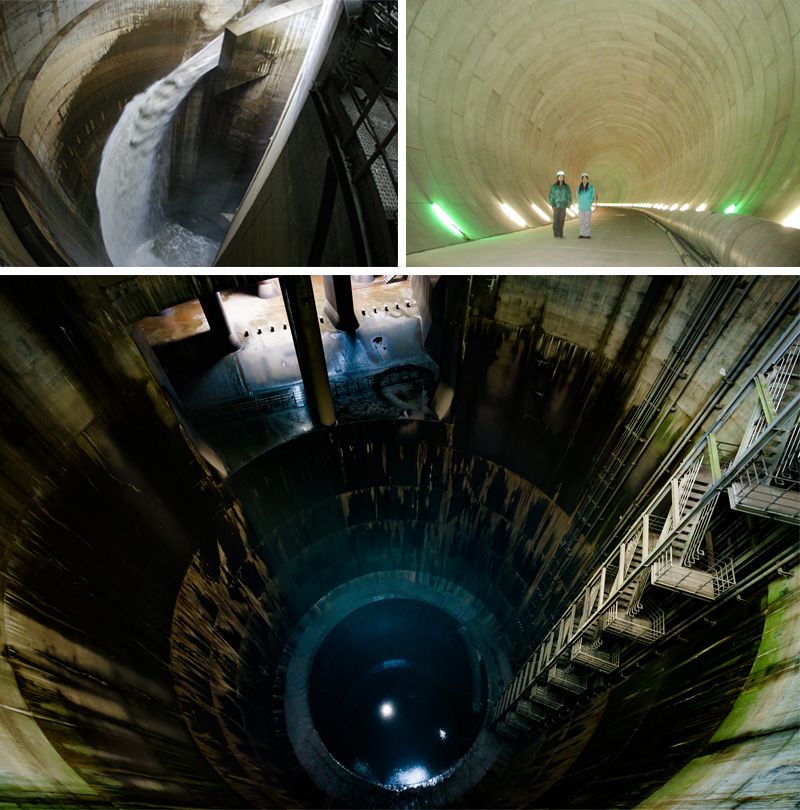

The pressure adjusting tank is just one part of the discharge channel. The entire system includes five vertical silos to collect water underground and a tunnel linking them that runs 50 meters underground below Highway 16. The silos are 70 meters tall and 30 meters in diameter, and the connecting tunnel has a diameter of 10 meters and stretches for 6.3 kilometers. Four powerful pumps, which are modified versions of the gas turbines used in jetliners, discharge the water into the Edo River. The pressure adjusting tank is located between silo No. 1 and the Shōwa drainage pump station and serves to control the reverse flow generated by an emergency shutdown of the pumps.

Overall view of the Metropolitan Area Outer Underground Discharge Channel. (Photo provided by the Edogawa River Office, Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport, and Tourism.)

Overall view of the Metropolitan Area Outer Underground Discharge Channel. (Photo provided by the Edogawa River Office, Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport, and Tourism.)

When a river rises during heavy rains or typhoons to the level of the lowest surrounding ground elevation, water is directed into a nearby silo. It flows into the tunnel that connects the base portion of all the silos and first accumulates there. When the tunnel is filled with water, the water level in the silos rises. If the water continues to increase, it flows into the pressure adjusting tank connected to silo number 1. The amount of water that the entire facility can contain is 670,000 cubic meters (equivalent to the volume of a 60-story skyscraper). When the water in the pressure adjusting tank reaches a predetermined level, the pumps in the drainage station begin to operate, discharging, at full operation, 200 cubic meters of water per second (equal to one 25-meter swimming pool) into the wide Edo River.

↑ Watch a video introducing the Metropolitan Area Outer Underground Discharge Channel.

Damage Prevented Is Three Times the Cost of Construction

The total cost of building the system was ¥230 billion. This was a huge sum of money, but it is being steadily recouped through operation. The system is used eight times a year on average, and since its partial opening in 2002 has taken in water and controlled flooding 105 times (as of October 25, 2016).

During a typhoon in July 2000, torrential rainfall of 160 millimeters was recorded in the basin of the Naka and Ayase Rivers, submerging 137 hectares of land under water and flooding 248 houses. When another typhoon drenched the basin with 199 millimeters of rainfall in October 2004 after the system had partially opened, the flood area was reduced to 72 hectares and the number of flooded houses to 126. After the full system came online, a low atmospheric pressure in December 2006 (resulting in rainfall of 172 millimeters) flooded only 33 hectares of land and 85 homes.

Data published by the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport, and Tourism shows that flood damage to houses, crops, and public facilities has been reduced by ¥48.1 billion over the 10 years since the system partially opened. If operated for 50 years, the system is projected to save ¥743.7 billion in flood damage—more than three times the cost of construction.

Upper left: Water flowing into a containment silo. Upper right: Inside the huge, 10-meter diameter underground tunnel. Bottom: Looking down into silo No. 1, which could easily house the space shuttle. The opening in the upper part of the photo is the pressure adjusting tank. (Upper two photos provided by the Edo River Office, Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport, and Tourism.)

Upper left: Water flowing into a containment silo. Upper right: Inside the huge, 10-meter diameter underground tunnel. Bottom: Looking down into silo No. 1, which could easily house the space shuttle. The opening in the upper part of the photo is the pressure adjusting tank. (Upper two photos provided by the Edo River Office, Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport, and Tourism.)

While acknowledging these actual and projected benefits, Yabe cautions that it is important not to overestimate its capacity.

“Of the eight times or so each year that rainwater drains into the tunnel, the pumps are put into operation about three times. The only times that all four pumps were running at full capacity were during two extraordinarily large typhoons in 2015. The system has tremendous flood control capacity, I think, but in the end what it protects against is the overflowing of rivers. It can’t completely prevent water damage. I hope that the people in the area will maintain a high level of awareness about disaster prevention and not be lulled into thinking that the discharge channel has made flooding a thing of the past.”

Upper left: The pressure adjusting tank can regulate water pressure when the drainage station turbine pumps are operating or are suddenly shut down. (Photo provided by the Edo River Office, Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport, and Tourism.) Upper right. The four turbine pumps of the drainage station. Bottom left: Sluice gates that discharge water into the Edo River. Bottom right: The Edo River is wide enough to accommodate water discharged from the drainage station.

Upper left: The pressure adjusting tank can regulate water pressure when the drainage station turbine pumps are operating or are suddenly shut down. (Photo provided by the Edo River Office, Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport, and Tourism.) Upper right. The four turbine pumps of the drainage station. Bottom left: Sluice gates that discharge water into the Edo River. Bottom right: The Edo River is wide enough to accommodate water discharged from the drainage station.

One of a Kind

Flood prevention works are becoming increasingly difficult to build above ground in the Tokyo metropolitan area, so many underground flood control facilities have been developed in recent years. Twenty-eight underground regulating reservoirs for 12 rivers are already in operation, and more than 10 others are planned or currently being built. Major projects include the Kanda River/Loop 7 Underground Regulating Reservoir, which has a tunnel that is 12.5 meters in diameter and 4.5 kilometers long, and the Furukawa Underground Regulating Reservoir, with a tunnel that is 7.5 meters in diameter and 3.3 kilometers long. Both are giant facilities that will greatly reduce flood damage.

Because they are underground flood control facilities, people often wrongly assume that they function in the same way at the Metropolitan Area Outer Underground Discharge Channel. Yet there are major differences.

“Regulating reservoirs reduce flood damage by temporarily holding water from overflowing rivers. The underground discharge channel, on the other hand, can not only hold water but also discharge it elsewhere, namely, the Edo River. That’s why it has a giant pressure adjusting tank and powerful turbine pumps,” says Yabe.

The discharge channel is therefore the only facility with an “underground temple.”

Upper left: The Ryūkyūkan on the grounds of the Shōwa Drainage Pump Station contains an exhibition hall and is the gathering place for tours of the pressure adjusting tank. Upper right: Visitors hear an explanation of the facilities from a staff member. Bottom left: A room showing videos on three screens. Bottom right: Visitors can look into the actual control room.

Upper left: The Ryūkyūkan on the grounds of the Shōwa Drainage Pump Station contains an exhibition hall and is the gathering place for tours of the pressure adjusting tank. Upper right: Visitors hear an explanation of the facilities from a staff member. Bottom left: A room showing videos on three screens. Bottom right: Visitors can look into the actual control room.

Foreign visitor are welcome to participate in the tour, but they should either be able to understand Japanese or be accompanied by an interpreter. On the day of our visit, a woman from Taiwan told us she came to the tour directly from Narita Airport, still carrying her suitcase. She was excited about the visit, telling us that a friend had found out about it on the Internet and “just had to see it. I speak Japanese and she invited me. Actually being inside is a really powerful experience, and we were blown away by Japanese technology. We have a lot of typhoons and floods in Taiwan, too, so I’d love to have this kind of facility there.”

Containment silo No. 1 seen from the pressure adjusting tank. The view of this side is also very popular.

Containment silo No. 1 seen from the pressure adjusting tank. The view of this side is also very popular.

Yabe says that public relations activities are especially important because this is an underground facility.

“Since it’s underground and normally hidden from view, people are more likely to misunderstand its role and facilities. We thus try to cooperate as much as possible with filming and to offer tours. The pressure adjusting tank is what brings everyone here and is what people want to use in filming, but of course it wasn’t built for that purpose. The Metropolitan Area Outer Underground Discharge Channel is full of things that were built for the first time in the world and features the highest levels of technology. This has contributed to its awe-inspiring atmosphere and functional beauty whose esthetic appeal is truly universal.”

The pressure adjusting tank viewed from the top of the stairs.

The pressure adjusting tank viewed from the top of the stairs.

Data

Metropolitan Outer Floodway Management Office, Shōwa Drainage Pump Station

- Address: 720 Kamikanasaki, Kasukabe, Saitama Prefecture

- Access: A 40-minute walk or a 7-minute taxi ride (about 3 km) from the north exit of Minami Sakurai Station on the Tōbu Noda LineNote: The Kasukabe City Community Bus, called the “Haru Bus,” goes near the office, but the days and times are limited.

- Ryūkyūkan hours: 9:30 am to 4:30 pm

- Entrance fee: Free

- For more information, visit the Metropolitan Area Outer Underground Discharge Channel website

With thanks to the Edogawa River Office, Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport, and Tourism

(Originally written in Japanese and published on November 22, 2016. Reporting by the Nippon.com editorial department. Photos by Miwa Noriaki)video movie tourism disaster Saitama exhibitions museum infrastructure rivers Saitama Prefecture Tokusatsu water underground Kasukabe City japanese technology