The Meiji Restoration: The End of the Shogunate and the Building of a Modern Japanese State

History Culture- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Black Ships and Unequal Treaties

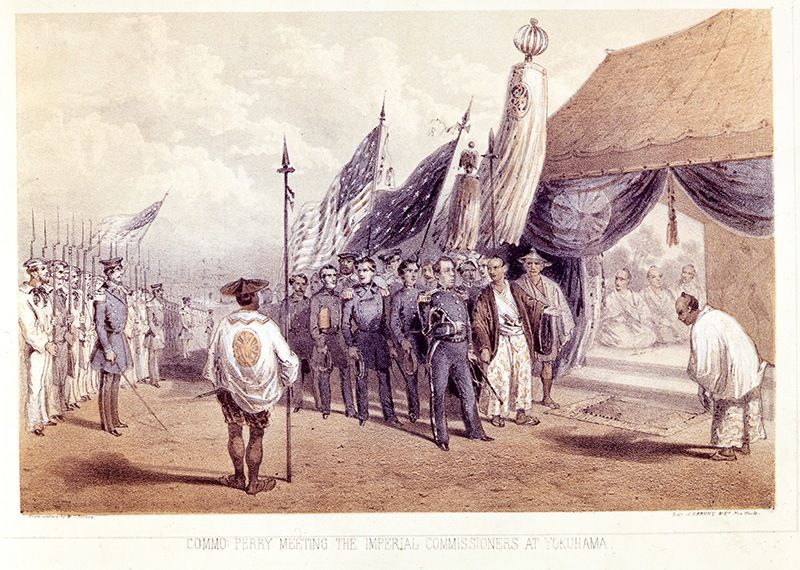

In the nineteenth century, after the world’s great powers successfully industrialized, they began expanding their influence to Asia in search of new markets. Foreign ships appeared in the seas around Japan, occasionally coming to shore with the aim of establishing trade ties. The Tokugawa shogunate, in power since the beginning of the seventeenth century, refused all these requests. In 1853, however, Commodore Matthew Perry of the US Navy, the commander of the East India squadron, arrived with a fleet of “black ships” and demanded the opening of the country. Seeing no other option, in 1854 the shogunate’s leaders agreed to the Japan-US Treaty of Peace and Amity, which opened the ports of Shimoda and Hakodate to US ships. Similar accords soon followed with Britain, Russia, and the Netherlands.

Japan went on to sign the Japan-US Treaty of Amity and Commerce in 1858. This was an unequal treaty, including clauses giving the United States the status of most-favored nation and fixing custom duties. The principle of consular jurisdiction in the agreement also meant that foreigners who committed crimes in Japan would be tried by their own country’s consular courts and could not be convicted by local judges. Custom duties were set extremely low and Japan could not alter them. As a result, the successive exports of large quantities of raw silk and tea led to domestic shortages, sending prices soaring. Conversely, imports of cheap cloth hit the earnings of Japanese cotton farmers and the fabric industry.

Commodore Matthew Perry and his men are welcomed to Yokohama. (Courtesy Yokohama Archives of History)

Commodore Matthew Perry and his men are welcomed to Yokohama. (Courtesy Yokohama Archives of History)

Opposition to the Shogunate Grows

The confusion of the opening of the country transformed into rancor against foreigners. In part because of the strong dislike for outsiders expressed by Emperor Kōmei (r. 1846–67), compared with the weak attitude of the shogunate, a movement to “revere the emperor and expel foreigners” (sonnō jōi) formed around the imperial leader. Ii Naosuke, who effectively headed the shogunate as tairō (great elder), tried to suppress this movement in a severe crackdown known as the Ansei Purge. Yet in 1860, he was assassinated on his way to Edo Castle by rogue warriors opposed to foreign influence in Japan. The Sakuradamon Incident—taking its name from the castle gate where the killing took place—was a serious blow to the shogunate’s prestige. The opposition movement, mainly led by samurai from the Chōshū domain (now Yamaguchi Prefecture), established control within the imperial court at Kyoto.

However, proponents of joint leadership by the court and shogunate (kōbu gattai), mainly from the domains of Aizu and Satsuma (now Fukushima and Kagoshima Prefectures), expelled the Chōshū samurai in 1863. The next year, Chōshū sent an army to try and enter the Kyoto Imperial Palace, but was repelled by armies from Aizu and Satsuma. The shogunate then launched a punitive expedition against Chōshū as an enemy of the court.

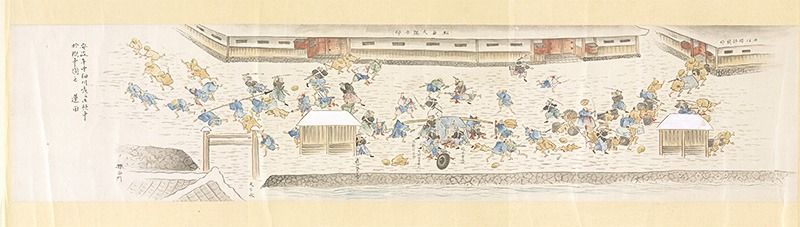

Ii Naosuke is assassinated outside Sakuradamon. (Courtesy Ibaraki Prefectural Library)

Ii Naosuke is assassinated outside Sakuradamon. (Courtesy Ibaraki Prefectural Library)

A Secret Alliance

The powerful domains of Satsuma and Chōshū experienced foreign military might in separate local conflicts with Britain and with a combined international force in 1863–64. This brought the painful realization that simply “expelling” the foreigners was impossible. To prevent Japan becoming a colony, it was necessary to rapidly construct a modern state. In 1866, the former rival domains secretly formed the Satsuma-Chōshū Alliance.

The same year, Satsuma refused to participate in a second expedition against Chōshū, instead supporting its ally by covertly supplying it with large quantities of arms. The shogunate’s defeat in this campaign against a single domain was a huge boost to the opposition movement.

Battles between shogunal and Chōshū forces in the second Chōshū Expedition. (Courtesy Yamaguchi Prefectural Museum)

Battles between shogunal and Chōshū forces in the second Chōshū Expedition. (Courtesy Yamaguchi Prefectural Museum)

Descent into Civil War

The last shogun, Tokugawa Yoshinobu (1837–1913), responded to the decline in shogunal authority with a statement in November 1867 peacefully relinquishing power (taisei hōkan) to the young Emperor Meiji—who had succeeded to the throne earlier that year after the death of Emperor Kōmei—although he still sought to participate in the new government at the imperial court. However, elements in Satsuma and Chōshū planned to overthrow the shogunate by force. In January 1868, they took control of the Imperial Palace in Kyoto, issuing an edict restoring imperial rule (ōsei fukko). This coup d’état is most commonly viewed as the key event of the Meiji Restoration. On the same evening, at a meeting of representatives of the new government, the hardliners won out against moderate elements from domains like Tosa and Echizen (now Kōchi and Fukui Prefectures) who favored compromise with Yoshinobu. The meeting decided that Yoshinobu must resign his offices and return all Tokugawa land to the court.

The Satsuma-Chōshū faction thereby aimed to provoke a violent reaction from the former shogunate, but Yoshinobu calmly retreated from Nijō Castle in Kyoto to Osaka Castle to observe the situation. The moderates in the new government gained the upper hand temporarily, and it was decided that Yoshinobu could become part of the cabinet. Yet when Satsuma samurai Saigō Takamori of the hardliners sent a group of warriors to stir up trouble in Edo, angry shogunate supporters burned the Satsuma domain residence in the city to the ground. Yoshinobu’s followers in Osaka were also enraged by these events, and as he was unable to control them he authorized them to advance on Kyoto. This set the stage for the Battle of Toba-Fushimi south of the city. In the first conflict of the Boshin Civil War, the forces of the new Meiji government defeated those of the former shogunate and Yoshinobu fled to Edo.

The last shōgun of the Edo shogunate, Tokugawa Yoshinobu. (Courtesy Fukui City History Museum)

The last shōgun of the Edo shogunate, Tokugawa Yoshinobu. (Courtesy Fukui City History Museum)

The Meiji Government

A huge Meiji government army of 50,000 men surrounded Edo, but negotiations between Katsu Kaishū, who led the shogunal forces, and Saigō Takamori resulted in the peaceful and unconditional surrender of Edo Castle. This avoided a devastating all-out attack on the city and guaranteed the safety of Yoshinobu. Resistance to the new government continued, however, in northern Japan through 1868 and into 1869.

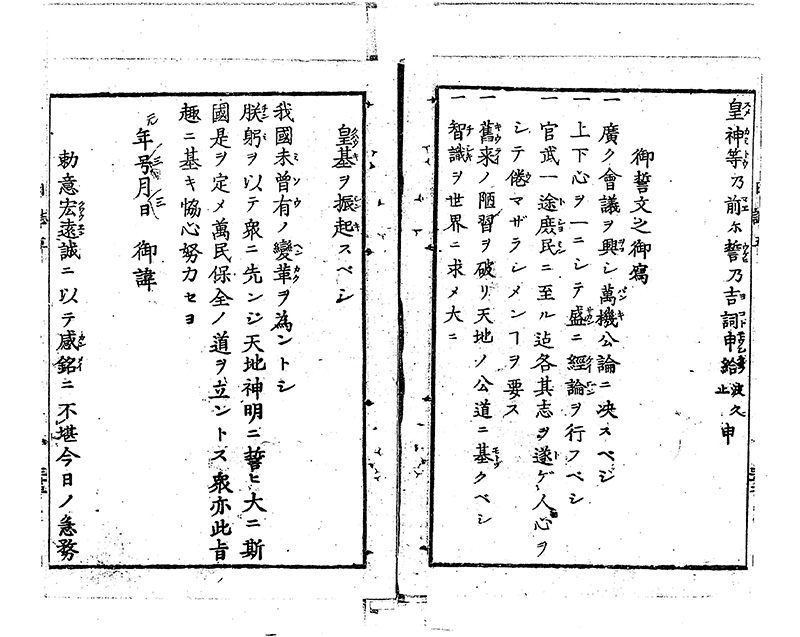

During this period, the Meiji government promulgated the Charter Oath, pledging respect for public opinion and amicable relations with other countries. With reference to the US Constitution, it drew up a document establishing a tripartite separation of powers. Under the new government, the emperor also moved to Edo Castle, which became the Imperial Palace; Edo was renamed Tokyo and became the nation’s capital, and the era name was changed to Meiji.

The Charter Oath published in 1868 by the Meiji government. (Courtesy National Diet Library)

The Charter Oath published in 1868 by the Meiji government. (Courtesy National Diet Library)

The Shogunate’s Last Stand

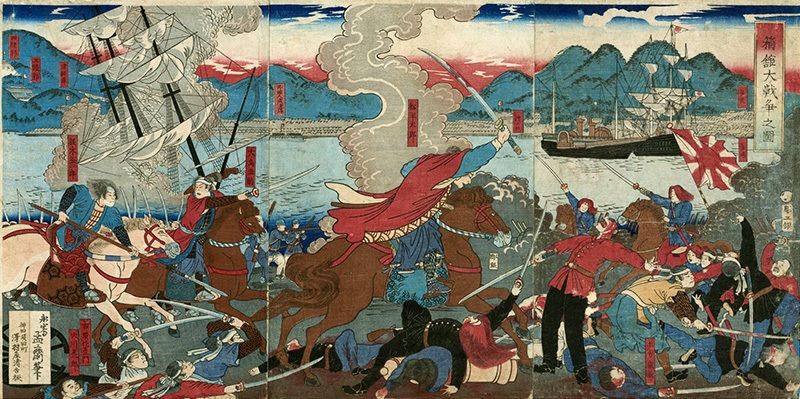

In June 1869, the last remnants of the former shogunate’s supporters commanded by Enomoto Takeaki surrendered at the fortress of Goryōkaku in Hakodate, Ezo (now Hokkaidō). This signaled the end of the Boshin Civil War, and the Meiji government now controlled all of Japan. The same year, it ordered the daimyō to return their territory and citizens to the state. This was purely cosmetic; while they received new titles replacing their powerful positions before, the domain leaders retained control over local politics.

What was more, many of the soldiers who had fought in the war returned to their various domains, leaving the national government with almost no military power. Foreseeing a second civil conflict, the domains began comprehensive military reforms. Kishū (now Wakayama Prefecture) was among those that introduced conscription and it built a modern Prussian-style force of 20,000 soldiers.

The Battle of Hakodate. (Courtesy Hakodate City Museum)

The Battle of Hakodate. (Courtesy Hakodate City Museum)

Prefectures and Centralization

Statesmen like Kido Takayoshi of Chōshū and Ōkubo Toshimichi of Satsuma feared that if nothing was done, the government might collapse. They decided to abolish all the domains, assembling 8,000 soldiers from Satsuma, Chōshū, and Tosa in Tokyo before announcing the change in August 1871. The domains were to be replaced by prefectures subordinate to a centralized government. The domain leaders were gathered in Tokyo for the announcement and ordered to reside in the capital.

Kido and Ōkubo anticipated great opposition to this revolutionary move, but it was completed with surprisingly little fuss. One major reason for this seems to have been the Meiji government’s announcement that it would cover the domains’ debts and pay the stipends of their samurai. In any case, the domains disappeared, and the new government succeeded in unifying the country politically. This laid the foundations for a remarkable social transformation over a short period. By rapidly modernizing, Japan aimed to build up its economic and military power and escape becoming a Western colony.

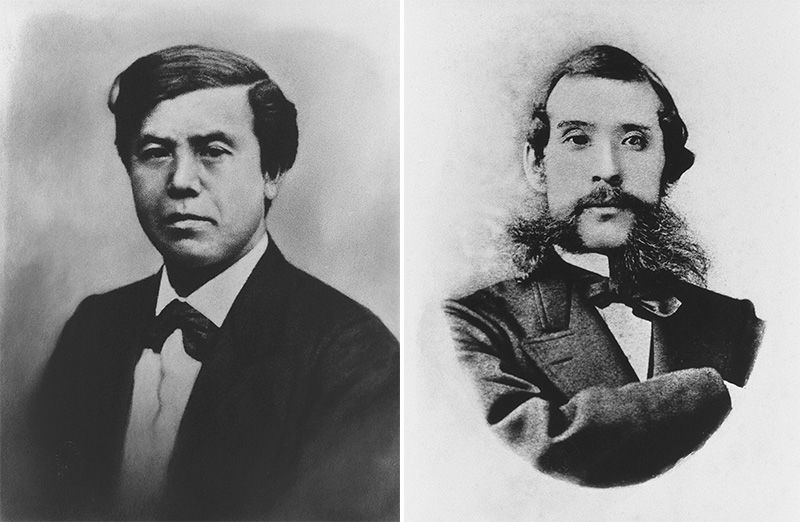

Kido Takayoshi (left) and Ōkubo Toshimichi, the architects of the prefectural system. (Courtesy National Diet Library)

Kido Takayoshi (left) and Ōkubo Toshimichi, the architects of the prefectural system. (Courtesy National Diet Library)

Samurai Rebellion

Under the shogunate, farmers were the main targets of taxation. Depending on the harvest, revenues could vary greatly from year to year. The Meiji government moved to set the tax burden on landowners, issuing bonds on which the value of land was written. In 1873, it made landowners responsible for paying a tax rate of 3% of the land value. This gave the government a reliable source of tax revenue, paid in cash rather than rice, which provided the stability for further modernization. The new government pushed forward with policies removing the previous class system—which had divided the population into samurai, farmers, artisans, and merchants—and establishing greater equality. It then introduced a three-year period of compulsory military service for males of 20 years of age. Japan’s first regular army consisted of these conscripts.

As the samurai no longer maintained their former dominance in the military realm, there was considerable discontent. With the replacements of domains by prefectures, they lost their main employers. Their hereditary stipends were gradually abolished and replaced entirely by government bonds in 1876. The use of surnames—once a prerogative for samurai only—was extended to the general population, while an edict prohibiting the wearing of swords was a further blow to the identity of the warrior class. For these reasons, the Meiji government faced successive samurai uprisings, most seriously in 1877, when Saigō Takamori turned against the government in the Satsuma Rebellion. The new national army applied its full power to successfully subjugating the insurgency, which was the last military threat to the Meiji government’s authority.

After this, discontented citizens sought to achieve change through what became known as the Freedom and People’s Rights Movement. The movement began with criticism by Itagaki Taisuke of Tosa of the monopolizing of power within the government by the Satsuma-Chōshū faction. He advocated the establishment of a national assembly allowing citizens to take part in government. The campaign grew from a small group of disgruntled samurai to encompass rich farmers and ultimately ordinary citizens.

The March 1877 Battle of Tabaruzaka was the last major conflict of the Satsuma Rebellion. (Courtesy National Diet Library)

The March 1877 Battle of Tabaruzaka was the last major conflict of the Satsuma Rebellion. (Courtesy National Diet Library)

The Meiji Constitution

Against this background, the government began to move toward drawing up a constitution. This was a pressing task for gaining Japan international recognition as a modern state and achieving revision of its unequal treaties, but the main reason for pushing ahead was the rise of the popular rights movement. In addition to demanding a national assembly, activists called for a constitution and produced many drafts themselves. These often stressed citizen rights and democracy, while some were of a radical character, influenced by the French Constitution. By contrast, high officials sought to shore up the power of the imperial and factional system, although even within the government there were voices like Ōkuma Shigenobu, who backed a progressive, British-style document.

Shaken by Ōkuma’s advocacy, the high officials dismissed him from the government in 1881 and sent Itō Hirobumi on a study tour to Europe. Having compared various European constitutions, Itō recommended taking the German system as a model, due to its strong emphasis on imperial power. When he returned to Japan, he made adaptations to reflect the local situation and submitted the document to the Privy Council, an advisory body to the emperor established to deliberate constitutional drafts.

The Privy Council discussed the legislation several times at meetings attended by Emperor Meiji before the Constitution of the Empire of Japan was promulgated on February 11, 1889. It was notable for describing the emperor as “sacred and inviolable” and stating that he held absolute power. He combined in himself sovereignty, the supreme command of the army and navy, and the power to appoint and dismiss the cabinet. At the same time, citizens were granted a wide range of rights, including freedom of religion, occupation, and speech—within the limits of the Constitution. Apparently, the inclusion of these rights was at Itō’s request.

The promulgation of the Meiji Constitution. (Courtesy Tokyo Metropolitan Library)

The promulgation of the Meiji Constitution. (Courtesy Tokyo Metropolitan Library)

Although Itō was one of the central figures in the Satsuma-Chōshū clique that ran the Meiji government, his later moves to strengthen party politics by founding Rikken Seiyūkai (Friends of Constitutional Government) show him to have been relatively liberal. By allowing the Constitution to be interpreted broadly, he also made possible a democratic reading of the country’s new basic law. This developed into the theory that the emperor himself was an organ of the state, as advocated by legal scholar Minobe Tatsukichi (1873–1948) in the twentieth century. At the same time, under a strictly literal reading, the emperor held supreme power. The former interpretation laid the foundation for the era of Taishō Democracy, while the latter was the basis for dark years of militarism and war. In any case, with its new Constitution, Japan established itself as Asia’s first modern state.

| 1853 | US Navy Commodore Matthew Perry arrives in Japanese waters with the “black ships.” |

| 1854 | Japan-US Treaty of Peace and Amity signed. |

| 1858 | Japan-US Treaty of Amity and Commerce signed. Start of the Ansei Purge. |

| 1860 | Shogunate leader Ii Naosuke assassinated outside Sakuradamon. |

| 1863 | Chōshū radicals expelled from Kyoto imperial court. |

| 1866 | Satsuma-Chōshū alliance formed. |

| 1867 | Shōgun Tokugawa Yoshinobu relinquishes power (taisei hōkan) to Emperor Meiji. |

| 1868 | Edict issued restoring imperial rule (ōsei fukko). Boshin Civil War begins with the Battle of Toba-Fushimi. Katsu Kaishū and Saigō Takamori agree on peaceful surrender of Edo Castle. New Meiji government promulgates the Charter Oath. Edo renamed Tokyo. Era name changed to Meiji. |

| 1869 | New government wins total control of Japan as Boshin Civil War ends. Domains return territory and citizens to the state. |

| 1871 | Domains replaced by prefectures. |

| 1876 | Prohibition of wearing swords and abolition of hereditary stipends cause discontent among samurai class. |

| 1877 | Satsuma Rebellion begins, but ends the same year with the ritual suicide of Saigō Takamori. |

| 1889 | Promulgation of the Meiji Constitution. |

(Originally written in Japanese. Banner picture: Emperor Meiji crosses the Tama River with his entourage on the way from Kyoto to settle in Tokyo. Courtesy Ōta City Local History Museum.)