Andō Momofuku: An Inventor Who Used His Noodle to Change Global Food Culture

Culture- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Early Entrepreneur, Late-blooming Inventor

Andō Momofuku (1910–2007) was rightly known as “Mr. Noodles.” His instant noodles, invented in 1958, record yearly sales of 5.5 billion units in Japan alone; worldwide, nearly 100 billion portions are consumed every year, truly making the product a “global food.” Nissin Food Products, the company Andō founded, is part of the Nissin Group, which has grown into a giant with net sales of more than ¥490 billion in the fiscal year ending March 2017.

The “Instant Ramen Tunnel” at the Cup Noodles Museum in Ikeda, Osaka, traces the evolution of Nissin Foods’ products over the years.

The “Instant Ramen Tunnel” at the Cup Noodles Museum in Ikeda, Osaka, traces the evolution of Nissin Foods’ products over the years.

But before success came many trials. Andō was an up-and-coming industrialist who lost all his wealth overnight. By the time he invented Chicken Ramen, the world’s first instant ramen, he was already 48 years old

Looking back on his invention, Andō left these words: “In life, it’s never too late. It took me forty-eight years to invent this product.”

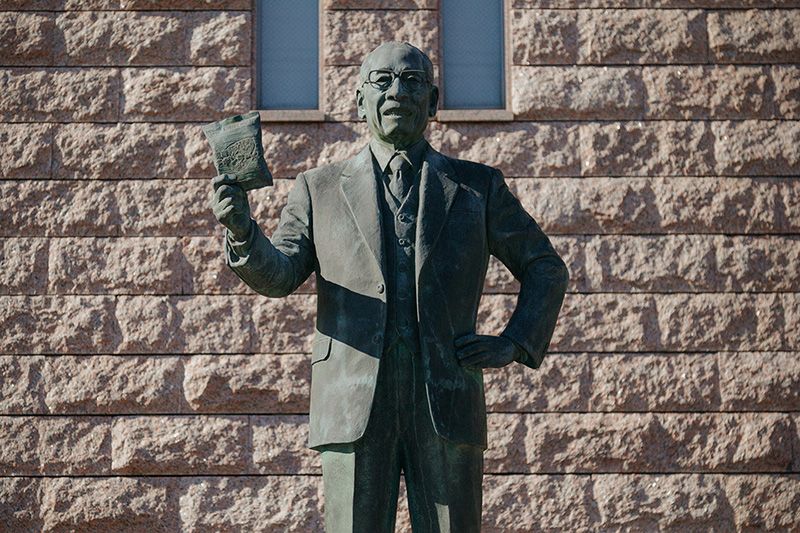

A statue of Andō Momofuku. The attractions and displays at the Cup Noodles Museum teach visitors about who Andō was, his successes, and the importance of the entrepreneurial spirit.

A statue of Andō Momofuku. The attractions and displays at the Cup Noodles Museum teach visitors about who Andō was, his successes, and the importance of the entrepreneurial spirit.

A Last-Ditch Effort for a Penniless Andō

Andō in the 1930s. After graduating from high school, he worked briefly as a librarian before becoming an entrepreneur.

Andō in the 1930s. After graduating from high school, he worked briefly as a librarian before becoming an entrepreneur.

Andō was born on March 5, 1910, in Taiwan, which was under Japanese rule at the time. Losing his parents at an early age, he, along with his two older brothers and a younger sister, was raised by his grandparents, who operated a kimono store in the city of Tainan. Seeing his grandparents at work as he was growing up, he came to see going into business as an interesting choice.

Aged 22, Andō set up a company in Taiwan to sell Japanese-made knitted fabrics. His business got off to a good start and the next year he opened a branch in Osaka, soon making a name for himself in the Kansai region as a young entrepreneur. Although he lost much of his business due to World War II, he was full of vitality and spirit as he branched out into manufacturing rudimentary postwar housing, producing salt, and founding a school.

Andō was jailed twice during his life. The first time, in the early war era, was for diverting military goods onto the black market. Following the war, he had his second brush with the law for tax evasion. Both times he was found innocent and released. Accusations against him had been made partly because he was a wealthy Taiwan-born businessman; he faced more than his share of troubles in the chaotic postwar years. During the war, he met and married his wife Masako, who supported him thereafter through thick and thin.

Happy couple Andō Momofuku and his wife Masako in their later years.

Happy couple Andō Momofuku and his wife Masako in their later years.

The greatest test in Andō’s life occurred when he was in mid-forties. In 1957, a credit union he headed went bust. With the exception of a rental property in Ikeda, Osaka, he lost all of his wealth overnight. The credit union role was one he had been asked to take on by a friend; he would later recall his “bitter regret” at having gone into the finance business, which he knew little about to begin with.

But he was quick to see that despite losing his assets, the experience would serve him well. It was very like him to quickly look for a way to get back on his feet. Here began his history as the “father of instant ramen.” Building a small workshop behind his house, he began developing a new product all by himself.

A life-size reproduction of Andō’s backyard workshop.

A life-size reproduction of Andō’s backyard workshop.

Tempura Provides the Spark of an Invention

The idea for instant ramen came to Andō at a black market near Osaka’s main train station during the years of severe food shortages following the war. Under a cold winter sky, he saw a long line of people lined up waiting their turn to eat a bowl of ramen. He was struck by the insight that food was important, and that without food, there could be no clothing, no housing, no art, and no culture. He also realized that Japanese loved noodles and was convinced that the long line of people standing outside represented pent-up demand. A few years later, when he did not know where his own next meal was coming from, he recalled that scene and decided to try developing ramen that was simple to make and easy to eat, in addition to keeping well.

Andō’s workshop, just 10 square meters in size. He used ordinary equipment and materials to develop his product.

Andō’s workshop, just 10 square meters in size. He used ordinary equipment and materials to develop his product.

Getting by just 4 hours of sleep a night, Andō doggedly kept at his research, never taking a day off for an entire year. The biggest hurdles to overcome were drying the noodles so they could be preserved for a long time and allowing them to be prepared for eating simply by pouring hot water over them. He finally came up with the flash-frying method, frying the noodles briefly to eliminate moisture.

Andō’s hometown of Tainan is known for yi-mian, a type of noodle that is deep-fried before boiling. Since the noodles keep for some time after they are boiled, some people say that yi-mian is the forerunner of instant ramen. In reality, though, Andō got the idea from his wife Masako’s tempura. Seeing how she prepared crispy tempura by frying it in a way that drove out excess moisture, he hit on the notion of flash-frying his noodles.

Chicken ramen was created using the principle of tempura.

Chicken ramen was created using the principle of tempura.

Thanks to Andō’s experimentation, Chicken Ramen, the world’s first instant ramen, went on sale in August 1958. The noodles are permeated with a concentrated soup consisting of chicken stock and seasonings; simply adding hot water produces a steaming bowl of ramen. Called mahō no rāmen, “magic ramen,” when it first went on the market, Chicken Ramen became a runaway hit.

When Andō first told Masako that he was going into the ramen business, she reportedly said: “If you’re going to do that, make sure you become Japan’s best ramen maker.” Her admonition came true, as Andō watched yearly sales of his Chicken Ramen reach ¥4.3 billion just five years later.

The first Chicken Ramen package. The package came with a transparent window displaying the noodles inside.

The first Chicken Ramen package. The package came with a transparent window displaying the noodles inside.

A Spark of an Idea That Changed the World

Thirteen years after launching Chicken Ramen, Andō once again surprised the world with Cup Noodle, the first prepackaged noodles to come in their own cup container. The move away from noodles packaged in bags may seem like a small change, but this was the first step in propagating made-in-Japan noodles to the whole world.

A standard Cup Noodle lineup today. The excellent package design and logo have remained virtually unchanged since the product’s launch.

A standard Cup Noodle lineup today. The excellent package design and logo have remained virtually unchanged since the product’s launch.

Andō got the idea for his new product on a 1966 sales trip to the United States. He was promoting Chicken Ramen to local buyers, but since there were no bowls or chopsticks at hand, he had no means of eating it right away to demonstrate. Seeing this, the supermarket buyer he was dealing with took out a paper cup, broke the noodles in half, poured in hot water and started eating them with a fork. This made Andō realize that taking local food customs into account was the key to conquering global markets. Putting all his ingenuity to work in five years of trial and error, Andō launched Cup Noodle in a disposable container in 1971.

Product development began with choosing a package for the noodles that would also serve as the preparation container and dining dish. This photo shows the cup’s inner structure; suspending the noodles above the base improves the cup’s durability.

Product development began with choosing a package for the noodles that would also serve as the preparation container and dining dish. This photo shows the cup’s inner structure; suspending the noodles above the base improves the cup’s durability.

But there were still hurdles to overcome. Priced slightly higher than bagged noodles, Cup Noodle didn’t move that well. Initially it was a niche product sold to people like police officers, firefighters, and others working night shifts or outdoors. But Andō persisted in his sales efforts. His big break came the next year, when the nation was transfixed by the Asama-Sansō incident, a hostage crisis and police siege in February 1972. In weather cold enough to freeze bentō box lunches solid, police spent more than a week attempting to force student radicals from a mountain lodge where they had taken the innkeeper’s wife hostage. The sight of them on nationwide TV hungrily slurping steaming cups of Cup Noodle gave the product a big boost among the public.

TV commercials boosted Cup Noodle’s popularity, as did the development of vending machines that also provided boiling water to prepare the product.

TV commercials boosted Cup Noodle’s popularity, as did the development of vending machines that also provided boiling water to prepare the product.

Space Noodles, the Next Frontier

The moment that Cup Noodles became a hit, rival makers entered the market, and the new product category of instant ramen spread worldwide. Andō, who believed that competition and friendly rivalry within the industry would help his own company grow, never sought to patent his invention, licensing it instead. This was a major factor behind the growth of the huge market for instant noodles—and one that ultimately contributed to the expansion of Nissin Foods itself.

Andō remained actively interested in developing new ideas throughout his life. In 2001, at the age of 91, he declared that he would develop space food. Leading his development team, he began working on ramen that could be eaten even in outer space. This led to his achievement of “Space Ram,” featuring a thickened soup to prevent splattering in a weightless environment. Andō’s creation made it into space in July 2005 together with Japanese astronaut Noguchi Sōichi and his crewmates on the space shuttle Discovery. Andō expressed pure delight and felt vindicated in his belief that “in life, it’s never too late” to do things.

“Space Ram” was produced in four flavors—soy sauce, curry, tonkotsu (pork broth), and miso—and featured various adaptations like bite-size noodle bunches.

“Space Ram” was produced in four flavors—soy sauce, curry, tonkotsu (pork broth), and miso—and featured various adaptations like bite-size noodle bunches.

Andō shaking hands with astronaut Noguchi after his space mission.

Andō shaking hands with astronaut Noguchi after his space mission.

Entrepreneurial Spirit Lives On

Andō died on January 5, 2007, aged 96, the day after he had presented his thoughts at the Nissin Foods New Year ceremony. His demise was reported around the world, and the New York Times ran an editorial expressing gratitude to “Mr. Noodles.”

Andō lived by the motto that “food brings peace.” He was honored for his social contributions through food and for promoting the development of food culture, including local culinary traditions in Japan.

Andō lived by the motto that “food brings peace.” He was honored for his social contributions through food and for promoting the development of food culture, including local culinary traditions in Japan.

Throughout his long life, Andō never ceased to come up with creative ideas or to bring tenacity to his endeavors. Many recall that when he was chairman of the company, there was a food preparation area adjoining his office where he could tinker with various food ideas. He was famous for aphorisms, one of the best remembered being: “If you fall, don’t just get up. Pick up some dirt while you’re at it.”

Those words— earthy, tough, and warm, and encapsulating a hard life of hurdles overcome—resonated with the public during Andō’s life. To this day, they serve to encourage anyone setting off on a new venture.

The Cup Noodles Museum in the city of Ikeda, Osaka, features a kitchen where visitors can experience preparing Chicken Ramen, the inspiration for Andō’s inventions.

The Cup Noodles Museum in the city of Ikeda, Osaka, features a kitchen where visitors can experience preparing Chicken Ramen, the inspiration for Andō’s inventions.