Beyond East and West: Okakura Kakuzō and “The Book of Tea”

History Culture- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

More than Just an Introduction to Japanese Aesthetics

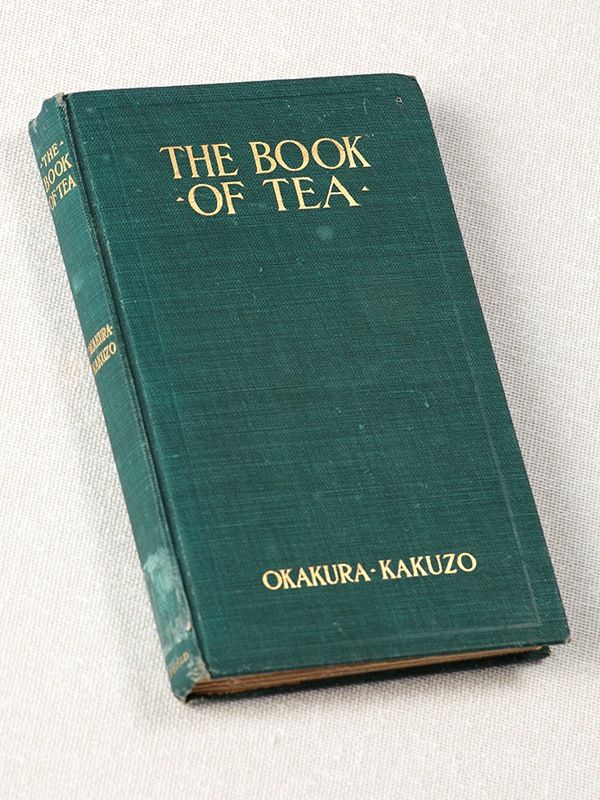

A first edition of The Book of Tea, published by Fox Duffield in 1906. (Photo courtesy of Ibaraki University.)

A first edition of The Book of Tea, published by Fox Duffield in 1906. (Photo courtesy of Ibaraki University.)

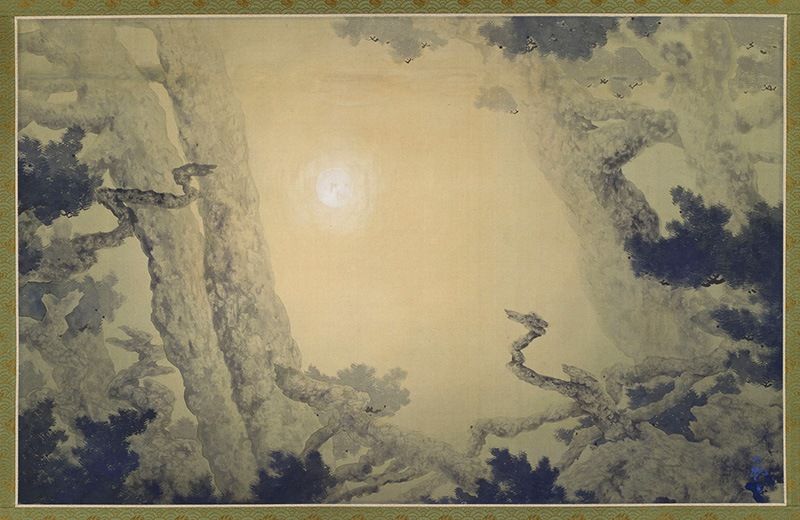

Multiculturalism and coexistence are pressing issues in contemporary societies, as the different parts of the world become more closely linked than ever before. But this greater familiarity has so far failed to lead to mutual understanding, and tensions and anxieties between states and peoples remain rife. More than a century ago, Japanese writer and thinker Okakura Kakuzō (1863–1913) compared the international struggle for supremacy and power to dragons “tossed in a sea of ferment,” who “in vain strive to regain the jewel of life.” In 1904, the same year that hostilities broke out between Japan and Russia, he moved to the United States, where he became the first Japanese curator of the department of Chinese and Japanese art at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. He wrote three books in English in which he shared with Western readers his insights into the art, history, and esthetic philosophy of Japan and the rest of Asia: The Ideals of the East with Special Reference to the Art of Japan, The Awakening of Japan, and The Book of Tea.

In The Book of Tea, published in the United States in 1906, Okakura suggested that our best hope in a world torn asunder by warring dragons was to wait for better days. Referring to a mythical Chinese goddess, he wrote: “We need a Niuka again to repair the grand devastation; we await the great Avatar.” And in the meantime? “Meanwhile,” he wrote, “let us have a sip of tea. The afternoon glow is brightening to bamboos, the fountains are bubbling with delight, the soughing of the pines is heard in our kettle. Let us dream of evanescence, and linger in the beautiful foolishness of things.”

Yokoyama Taikan, “Two Dragons Fighting Over a Precious Jewel,” monochrome ink on silk, 1905. The painting imagines the pine trees as two dragons and the moon as a jewel. (Photo courtesy of the Yokoyama Taiken Memorial Hall.)

Yokoyama Taikan, “Two Dragons Fighting Over a Precious Jewel,” monochrome ink on silk, 1905. The painting imagines the pine trees as two dragons and the moon as a jewel. (Photo courtesy of the Yokoyama Taiken Memorial Hall.)

Okakura’s words are an invitation to leave the troubled seas behind and step into the light for a shared cup of tea. The drink now widely enjoyed in the West is brewed with leaves that originate in the East. Tea has become an essential part of Western life, and the practice of enjoying a moment’s reflection and repose over tea is something universal, which unites people in nations across the world. The interactions between a hostess and her guests at an afternoon tea involve practices of courtesy, hospitality, and conversation very similar to those seen in Japanese tea ceremony etiquette. A similar reverence for tea can be found in both East and West—perhaps because of this, Okakura thought: “humanity has so far met in the tea-cup.”

The Book of Tea is often understood as a work that sought to introduce Japanese culture to Western audiences through the prism of the tea ceremony. But the book contains a larger message. While acknowledging the cultural differences between East and West, the book argues that both are equal, and that if both sides acknowledge the diversity of values and the validity of cultural differences, and learn to show interest and respect for each other, then peace and harmony between them is possible. Okakura skillfully used the tea ceremony to argue that the cultural exchanges that bring people together on a daily basis through the humble act of enjoying a cup of tea can be put to a wider use on the global stage. This, I believe, is why the book continues to be read and valued by people around the world today.

Western Learning and Japanese Traditions

What kind of person was the man who wrote these books? In textbooks of Japanese history, Okakura is normally cited for his role in establishing the Tokyo Fine Arts School (today the Tokyo University of the Arts), from which Yokoyama Taikan (1868–1958) and other nihonga painters emerged, and the Nihon Bijutsuin (The Japan Art Institute), dedicated to Japanese-style painting. He made an essential contribution to the development of modern Japanese art, working to promote and support a new type of artistic endeavor that would match the sensibilities of the new age while remaining firmly rooted in Japanese traditions. He also did important work to preserve and restore traditional artworks that were damaged in the wave of anti-Buddhist iconoclasm and violence (haibutsu kishaku) that broke out around the time of the Meiji Restoration in 1868. His activities later took him overseas, and he spent the last decade of his life in the United States as a curator in charge of the department of Chinese and Japanese art at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, where he helped to make the museum a major center for East Asian art in the United States and trained a new generation of American curators in Asian art.

Okakura’s life and achievements mean that he is normally seen as an international figure equally at home in East and West. His cosmopolitan nature was cultivated in the hybrid cultural environment of the Meiji era (1868–1912), when Okakura had a foot in several worlds at once: Yokohama, Fukui, and Nihonbashi; trader and samurai; Western civilization and the world of the traditional Japanese arts. His father was a low-ranking samurai from Fukui who was sent to Yokohama as a merchant for the domain when the port was opened to international trade, and displayed a talent as an agent. After the Meiji Restoration, his family relocated to the Nihonbashi area of Tokyo, and opened an inn and trading house dealing in silks and other goods from Echizen (now Fukui Prefecture). The younger Okakura studied English in Yokohama and absorbed Western learning from foreign teachers at the University of Tokyo, while simultaneously training in traditional Japanese arts in Nihonbashi: Chinese poetry, nanga painting, koto, and the tea ceremony. He absorbed Western modernity and East Asian traditional culture at the same time, the two fusing together within him into a coherent whole.

After graduating from the University of Tokyo, Okakura joined the Ministry of Education, Science, and Culture, where he played a leading role in introducing art policies suited to the new age and became the second dean of the Tokyo Fine Arts School. For a while, everything seemed to be plain sailing, but a love affair with Hatsuko, the wife of Kuki Ryūichi, his superior at the ministry, cast a shadow over his home life. Around the same time, tensions arose within the movement to introduce Western-style education. He eventually lost his position as dean of the Tokyo Fine Arts School, leading to chaos as many of the artists and faculty resigned in protest at his treatment. Okakura went on to found the Nihon Bijutsuin (The Japan Art Institute) with the painters, sculptors, and craftsmen who had resigned in support. Although the new academy was founded on strong ideals, its new style of painting was not immediately popular. Led by Yokoyama Taikan and Hishida Shunsō, the new style did away with the strong lines of traditional painting in favor of a softer approach. It was poorly received and criticized as “vague” and “blurry” (mōrōtai). The academy ran into financial difficulties and Okakura’s new enterprise started to struggle.

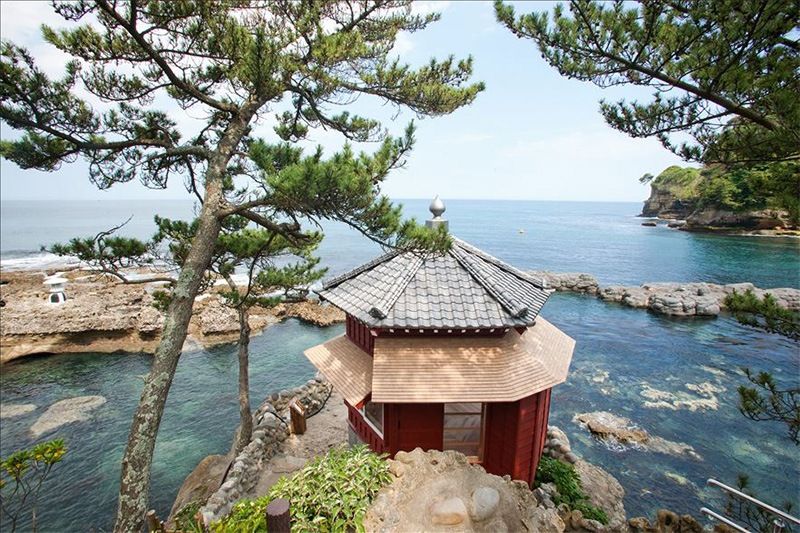

The Rokkakudō, which Okakura built on the Izura coastline of northern Ibaraki Prefecture in 1905 as a place for retreat and reflection. The building was swept away in the Tōhoku tsunami of March 11, 2011, but was rebuilt in 2012. (Photo courtesy of Ibaraki University)

The Rokkakudō, which Okakura built on the Izura coastline of northern Ibaraki Prefecture in 1905 as a place for retreat and reflection. The building was swept away in the Tōhoku tsunami of March 11, 2011, but was rebuilt in 2012. (Photo courtesy of Ibaraki University)

Internationalist and Thinker

As he pondered his future after these personal and professional setbacks, Okakura visited India. One of the things that drew him there was a desire to visit Swami Vivekananda (1863–1902), the Hindu monk who had won numerous followers with his impassioned plea for religious harmony at the World’s Parliament of Religions held in Chicago in 1893. Vivekananda introduced the truths of the ancient religions of India to the West, acknowledging the universal elements in both Western and and Eastern philosophy and urging greater exchanges between the two. This appeal to intercultural harmony must have resonated with Okakura, who was engaged in his own creative endeavor to blend the traditions of Japanese and European art. In The Book of Tea, Okakura wrote: “In the liquid amber within the ivory-porcelain, the initiated may touch the sweet reticence of Confucius, the piquancy of Laotse, and the ethereal aroma of Sakyamuni himself.” The essence of the tea cult was a harmonious combination of Confucianism, Daoism, and Buddhism: a diversity that encompassed the best elements of many different philosophies, without being tied down by any single religion or tradition.

During his time in India, Okakura also struck up a close friendship with Rabindranath Tagore (1861–1941). Tagore was born in Calcutta (Kolkata) and received the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1913 for his rich output of poetry, plays, and novels in Bengali. By the time of Okakura’s visit, he was one of the most famous figures in contemporary Indian culture. Tagore traveled the world introducing international audiences to Indian culture and thought, and calling for world peace and international cooperation. Okakura spent time with the artists who gathered around Tagore, and sympathized with the Indian nationalists seeking to free the country from British colonial rule.

Rabindranath Tagore. (Photo courtesy of Ibaraki University)

Rabindranath Tagore. (Photo courtesy of Ibaraki University)

As representative figures from Asia at a time when Western civilization seemed to occupy a position of unrivaled superiority, men like Okakura, Vivekananda, and Tagore worked to bring a better understanding of the traditional cultures of their homelands to people in the West—art, religion, history, and the culture of daily life. Common to all three was a readiness to appeal to the universal elements in “Western” and “Eastern” cultures, and a determination to seek a respectful exchange and harmony between them.

In India, Okakura came to understand the Asian nature and origins of Japanese art. This understanding became the basis for his life in Boston, where he worked to share Japanese culture and thought with the world. At the start of his time in Boston, he compared the United States to a “halfway house” between the West and the East, and argued that building an outstanding collection and learning to appreciate artworks from another culture could play a significant role in helping East and West to understand each other better. Okakura saw the United States as a place where the two cultures could come together in a new understanding; the aim of making the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, into a new kind of international meeting place lay at the core of his approach as a curator. With a staff of Japanese and American helpers, he put down the foundations of one of the outstanding East Asian art collections in the United States. The curators he trained later took jobs in museums around the country, and devoted themselves to cultural exchanges between the two countries right up to the outbreak of the Pacific War in 1941.

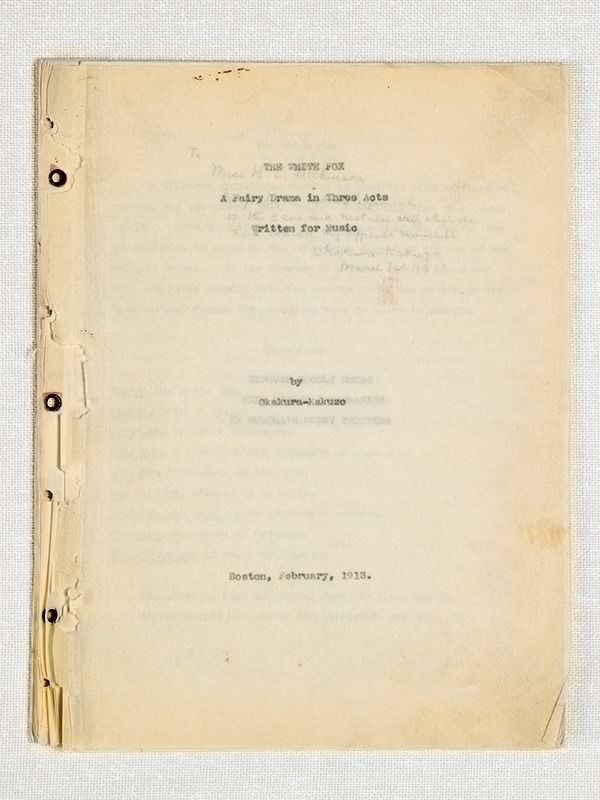

The libretto for the White Fox, completed in Boston in 1913. (Photo courtesy of Ibaraki University)

The libretto for the White Fox, completed in Boston in 1913. (Photo courtesy of Ibaraki University)

Okakura’s final work was The White Fox, an opera libretto based on the legend of Shinodazuma (the story of a white fox in the Shinoda forest who takes the form of a beautiful woman, marrying a man named Abeno Yasuna and having a child with him before her true identity is discovered and she returns to the forest). Okakura uses the Western opera form to create a work with universal themes: a mother’s love for her child, and the pain of separation. The child born of the union between fox and human is a miraculous being who links two irreconcilable worlds. When his mother has to return to the forest, she leaves her son with a magic ball that predicts a future that will bring harmony between the two worlds. Here we can surely discern echoes of the “jewel of life” for which the competing dragons were fighting in the opening passages of The Book of Tea.

More than a century after Okakura’s life came to an end, countless dragons continue to fight for supremacy and power in a “sea of ferment.” As the world plummets ever deeper into chaos and confusion, humanity has yet to find a way to restore order and repair the ruin and depredation caused by centuries of conflict. Now, more than ever, we should return to Okakura’s ideas—his philosophy of wisdom and tolerance is more important than ever in an age when the tensions between states and peoples seem more intense and threatening than they have been for some time.

(Originally published in Japanese on August 2, 2018. Banner photo: Okakura Kakuzō (also known as Okakura Tenshin), taken at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, in around 1904. Photo courtesy of Ibaraki University)

art tea ceremony Meiji era The Book of Tea Okakura Kakuzō Okakura Tenshin