Customs and Manners Japanese Style

A Cultural History of Noodle Slurping

Guideto Japan

Culture- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

The author, a soba enthusiast, demonstrates the proper way to eat Japanese buckwheat noodles.

The author, a soba enthusiast, demonstrates the proper way to eat Japanese buckwheat noodles.

Few foods in Japan are more popular than noodles, a favorite among natives and tourists alike. After all, what’s not to like about a delicious, quick, and inexpensive meal of soba (buckwheat noodles), udon (thick wheat noodles), or ramen? Yet last year, the noodle briefly emerged as a focus of heated debate when an anonymous Japanese tweeter began holding forth on the subject of “noodle harassment.” The gist of the rant was that the Japanese custom of slurping one’s noodles is not merely offensive to foreigners but actually qualifies as a form of harassment—nū-hara for short. The comments were widely retweeted, and the topic spilled over into the mainstream media, eliciting passionate responses pro and con.

Cooler heads eventually prevailed, as it became clear that the original tweeter had fabricated a controversy more or less out of thin air. Still, there is no denying that noodle slurping is a distinctively Japanese custom that tends to provoke reactions ranging from amusement to disgust among foreigners exposed to it for the first time. After all, noodles of various types, from spaghetti to lo mein, are consumed the world over, but slurping is sanctioned almost nowhere outside of Japan.

A Question of Olfaction?

It’s not that Japanese table manners are inherently permissive when it comes to slurping. In Japan as elsewhere, noisy eating is generally frowned upon, particularly in formal social situations. Why, then, have the Japanese created a special exemption for noodles? As a longtime soba aficionado and critic, I was keen to get to the bottom of this mystery. I decided to start out by asking the opinion of one of Japan’s foremost noodle experts: Horii Yoshinori of the venerable Sarashina Horii in Tokyo’s Azabu Jūban district, a 220-year-old soba shop popular among locals and tourists alike.

Horii offered a surprisingly scientific explanation.

“I would say that slurping developed as a way to better savor the aroma of soba,” he suggested. “The smell of soba is best appreciated via the mouth, not the nose. With wine tasting, for example, you first sniff, to smell the wine in the glass, then you swish it around in your mouth to capture the aroma that wafts up your nasal passages from your throat. They call it orthonasal olfaction and retronasal olfaction, respectively. Soba is difficult to smell by the first route, so we make the most of the second.”

Horii explained that the distinctive fragrance of soba comes through clearly during the cooking process, especially when the soba is steamed in bamboo steamers, as it was in the early days. “People would have smelled the aroma from the steam that escaped,” he says. But the aroma of cooked soba is much subtler. “This is especially true for chilled mori soba. There’s no aromatic steam rising up from the cold noodles, so even if you actively sniff them, there’s not much to smell. But when you slurp them vigorously, you can fully experience the aroma exploding in your mouth. That’s the correct way to eat soba.”

Indeed, from a Japanese viewpoint, it seems rather a shame (and a bit uncool) to quietly chew one’s noodles. But how did Japanese society as a whole come to embrace a behavior so out of synch with conventional table manners? I drew on some of my own historical research, as well as Horii’s valuable insights, to come up with a plausible explanation.

Chef-owner Horii Yoshinori of the famed Sarashina Horii soba shop, established in 1789.

Chef-owner Horii Yoshinori of the famed Sarashina Horii soba shop, established in 1789.

Convenient Nutrition for the Masses

Buckwheat (also known as soba in Japanese) has been grown and consumed in various parts of Japan for centuries. It is high in nutritional value, and it matures quickly, especially compared with rice—just two-and-a-half to three months from planting to harvest. In early times, buckwheat groats were cooked into a porridge or gruel. Later, people began to grind the buckwheat into flour and make it into dumplings. In time, the dumplings evolved into soba noodles.

Soba noodles first appear in the historical record in the early Edo period (1603–1868). By the late seventeenth century, quite a few soba shops had sprung up around the fast-growing city of Edo (modern-day Tokyo). Initially offered as an additional menu option alongside the more familiar udon, soba soon eclipsed its wheat-based cousin and took its place as one of Edo’s culinary specialties.

The nutritional value of buckwheat was doubtless a major reason for soba’s popularity. Compared with refined wheat flour, buckwheat is high in protein and important B vitamins. While the consumers of the time may have lacked access to “nutrition facts” as such, experience taught them which foods supplied the nutrients they needed to stay healthy. By 1800, near the end of the Edo period, Edo boasted roughly 700 soba shops. That made it the second-largest category of food and beverage service, after the casual drinking spots known as izakaya.

“Edo was a city of one million people back then,” says Horii. “It was one of the world’s biggest urban centers. To survive in that bustling, competitive environment, people needed easy access to quick, nutritious meals. That could be one of the reasons that soba took root in Edo, while udon continues to rule in the Kansai [Kyoto-Osaka] region.”

The main attraction at Sarashina Horii is the shop’s famous Sarashina soba (¥930). The thin, pale noodles, made from highly polished buckwheat, are fine-grained and fragrant—and ideally suited for slurping.

The main attraction at Sarashina Horii is the shop’s famous Sarashina soba (¥930). The thin, pale noodles, made from highly polished buckwheat, are fine-grained and fragrant—and ideally suited for slurping.

Soba as Street Food

Many busy Edoites purchased and consumed their soba at food stands, or from mobile “night hawkers” who carried their wares about on shoulder poles. To be sure, there were also some upscale soba shops where high-ranking samurai and other relatively well-heeled patrons could gather to eat at their leisure. But at heart, soba was street food for the common folk. (It was also the street vendors of the Edo period who popularized two foods now virtually synonymous with Japanese cuisine: sushi and tempura. They, too, got their real start as street food that busy townspeople could buy and eat on the go.)

Of course, by the Edo period, the Japanese people already had a well-developed table etiquette, not so different from that observed today. Eating noisily, as one might suppose, was considered bad manners. But as Horii points out, “this was the food of the common folk, so they didn’t worry too much about formal table manners.”

Moreover, street stands were by nature places where people dashed in to grab a quick bite—often standing up—on their way to or from work or some other destination. Under the circumstances, it probably seemed natural to slurp up one’s noodles. In a street-smart place like Edo, only haughty diners would have complained about “bad manners.”

All in all, it seems probable that the custom of noodle slurping originated at soba stands, then spread, and continued into modern times, influencing the way the Japanese eat ramen and other noodles as well.

After slicing a batch of noodles, the soba maker carefully gathers them into a neat bundle.

After slicing a batch of noodles, the soba maker carefully gathers them into a neat bundle.

I’d Like to Teach the World to Slurp

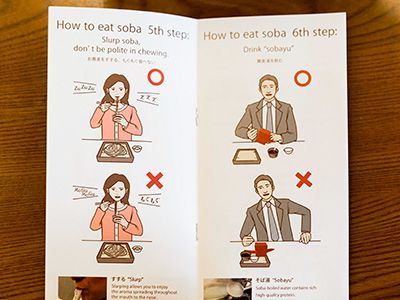

Sarashina Horii’s English-language pamphlet illustrates the finer points of soba eating.

Sarashina Horii’s English-language pamphlet illustrates the finer points of soba eating.

The verdict is in: Slurping is the best way to eat soba noodles. So, why not teach the world to slurp instead of fretting over something as silly as “noodle harassment”? In fact, Sarashina Horii has printed up an illustrated English-language pamphlet for diners interested in learning more. But Horii denies any zeal to spread the gospel of slurping.

“I don’t tell anyone how to eat,” he insists. “Those that can’t slurp chew. I’m more concerned that they appreciate how delicious and nutritious soba is. You can’t force something like that on people. Hopefully, as they eat, they’ll discover that it tastes better when they slurp. The main thing is that my customers enjoy their noodles.”

Slurping noodles is a custom extending back to the Edo period and an integral part of Japan’s food culture. We need not abandon such a custom for fear of committing “noodle harassment,” but neither should we force it on others. It should be enough for us if visitors from abroad appreciate our food, regardless of how they choose to eat it. As Horii says, enjoying mealtime is more important than adhering to this or that book of etiquette.

Sarshina Horii displays its offerings in a food sample case and also provides an English menu.

Sarshina Horii displays its offerings in a food sample case and also provides an English menu.

Even so, a certain amount of education takes place naturally at Sarashina Horii. The “instructors” are generally older Japanese patrons from the neighborhood, many of whom learned to speak English growing up, thanks to the large number of foreign residents working at embassies in the area. They enjoy engaging foreign diners in friendly conversation, and if the subject of slurping comes up, they gladly share their know-how. In this way, Sarashina Horii is spreading the good word—about soba and slurping—in the best way possible.

Sarashina Horii at Azabu Jūban

3-11-4 Moto-Azabu

Minato-ku, Tokyo

Tel: 03-3403-3401

Monday–Friday: 11:30 am–8:30 pm

Saturday, Sunday: 11:00 am–8:30 pm

(Open everyday, year-round)