Growth of a Great City from the Seeds of Ieyasu’s Edo

History Culture- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Tokyo is the largest megacity in the world according to The World’s Cities in 2016, a data publication from the United Nations. The Tokyo urban agglomeration—the metropolis itself, along with its surrounding urban sprawl reaching into the neighboring prefectures of Kanagawa, Saitama, and Chiba—has 38 million inhabitants, more than the population of Canada.

This busy metropolis full of people ceaselessly weaving their way through clusters of high-rise buildings and mazes of roads, subways, and trains has a long repeating history of growth and destruction that started more than 400 years ago in an expanse of scrubby forests and dank marshes.

Birth of a Great Metropolis

Tokyo’s origins go back to 1590, when the hegemon Toyotomi Hideyoshi ordered Tokugawa Ieyasu, then a regional lord who ruled an area around what is now Nagoya, to move his domain to the Kantō region. Ieyasu complied by moving his base to a small village called Edo. The current Imperial Palace sits on the site of the Edo Castle, which was at the time of Ieyasu’s move situated at the head of an inlet with a village precariously clustered along the narrow strip of land before it. After he came to power and established the Tokugawa shogunate, one of the first things Ieyasu did was to remedy the lack of land by filling in the inlet with earth carved out of Kandayama, a hill to the north of the castle. This landfill was to later become what is now the Marunouchi-Yūrakuchō area of Tokyo. The castle was protected by inner and outer moats but could be accessed by a network of canals dug to facilitate the transport of goods.

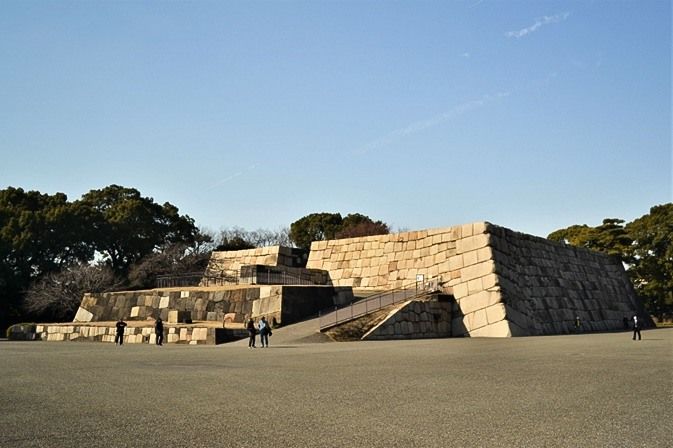

The foundation of Edo Castle’s main keep was rebuilt after the 1657 Great Fire of Meireki. The base is built of granite and measures 11 meters high, 41 meters east to west, and 45 meters north to south. The structure is located in the East Garden of the Imperial Palace grounds, which is open to the public.

The foundation of Edo Castle’s main keep was rebuilt after the 1657 Great Fire of Meireki. The base is built of granite and measures 11 meters high, 41 meters east to west, and 45 meters north to south. The structure is located in the East Garden of the Imperial Palace grounds, which is open to the public.

Under Tokugawa rule, Edo grew into a town and then a city. One of the driving forces behind its rapid development was the sankin kōtai system enforced by the shogunate. Under this system, all of the daimyō lords were required to live in Edo every other year. This involved long processions throughout the country as the daimyō and their vassals travelled back and forth between Edo and their own domains. They were also forced to leave their wives and heirs in the city as de facto hostages whenever they left. While in Edo, the daimyō lived in large mansions on land assigned to them by the shogunate in and around Edo Castle and along the high ground to the west. Commerce flourished to meet the needs of the many daimyō and their samurai retinues. While there is no accurate data to verify, it is believed that by the eighteenth century there were more than 1 million people living in Edo, making it one of the largest cities in the world at that time.

Edo was a busy city, and the focal point of much of its activity was the Nihonbashi district named after the bridge built in 1603, the year in which Ieyasu was awarded the title of seii taishōgun, literally “barbarian-subduing generalissimo”—making him the de facto ruler of all Japan—and the official start of the Edo period (1603–1868). The year after Nihonbashi was built it was designated as the starting point for the five major highways leading out of the city, the Tōkaidō, Nakasendō, Nikkō Kaidō, Koshū Kaidō, and Ōshū Kaidō. These highways were not only the major routes for the daimyō processions but also served as busy thoroughfares for a constant stream of travelers going to and from points all over the country.

A City of Ashes and Rebirth

Much of Edo’s burgeoning population was squeezed into the shitamachi districts in the low-lying riverfront environs of the city, where commoners lived in poorly built wooden structures divided into small units. Fires caused by carelessness and sometimes arson were frequent. Every few years there would be a fire large enough to burn large swaths of the city to the ground. So common were fires, in fact, that they were considered one of Edo’s major “attractions.” Fires and fights, it was proudly claimed, were the hallmarks of the great city.

One of the most devastating fires was the Great Fire of Meireki which broke out in the winter of 1657, the third year of the Meireki era. There are different reports on the extent of the conflagration, but it is generally believed to have destroyed 60% of the city center, including what are now the cities of Chiyoda, Chuō, and Bunkyō. Even Edo Castle was destroyed, with only the Nishi-no-maru main keep left standing. It was later reported that 550 daimyō mansions, 770 mansions belonging to direct retainers of the shōgun, 350 temples and shrines, and 60 bridges were burned completely.

After this disaster, the shogunate moved quickly to rebuild the city. The mansions of the three main Tokugawa family branches—the Owari, Kii, and Mito clans—and some of the daimyō estates that had been located within the castle grounds were moved out to be replaced by horse stables, paddocks, and herb gardens that would act as fire breaks. This move had a domino effect, and new areas to the east in Honjō and Fukagawa across the Sumida River were developed to accommodate the mass move of daimyō mansions and temples and shrines. Townspeople burned out of their homes were likewise moved en masse to the Tama and Mitaka areas to the west. Every major fire in Edo only served to push the city borders out further. What had started as a tiny village on an inlet grew in less than a century of Tokugawa rule into a major metropolis often referred to as the Great Edo of Eight Hundred and Eight Towns (Ō-Edo happyaku-ya chō).

The Meiji Government’s Use of Western Technology

In the Meiji Restoration of 1867, the Tokugawa shogunate came to an end and Japan’s leadership reverted to the emperor. The nation’s capital, which had been in Kyoto for over 1,000 years, was moved to Edo and the name of the former Tokugawa stronghold was changed to Tokyo, the capital of the east.

In its determination to modernize, the Meiji government actively recruited foreigners to work in government agencies and universities to introduce the advanced technologies and ideas of the West. In 1872, Japan’s first railway began operation, a line linking Shinbashi in Tokyo to the city of Yokohama that was built under the supervision of Edmund Morel, a British civil engineer. The wooden daimyō mansions around the imperial palace—site of the former Edo Castle—were demolished to make way for brick and stone buildings designed by foreign architects. The former Ministry of Justice Building, a grand red brick structure now known as Central Government Building No. 6, was designed by the German architects Hermann Ende and Wilhelm Böckmann and built in 1895 on the site of the former Uesugi mansion, the Edo home to the lords of the Yonezawa domain.

The former Ministry of Justice Building in the Kasumigaseki district of Chiyoda. Only the exterior red brick walls were left after the 1945 firebombing of Tokyo at the end of World War II. The building exterior was restored as part of a 1994 renovation, and it continues to house government offices. The Ministry of Justice Museum on the third floor is open to the public.

The former Ministry of Justice Building in the Kasumigaseki district of Chiyoda. Only the exterior red brick walls were left after the 1945 firebombing of Tokyo at the end of World War II. The building exterior was restored as part of a 1994 renovation, and it continues to house government offices. The Ministry of Justice Museum on the third floor is open to the public.

When the Mitsubishi Company purchased a large swath of land in front of the imperial palace from the Meiji government, it sought to build a modern business district that would resemble the City of London financial district. To this end, the company hired Josiah Conder, a British architect who had chosen to remain in Japan after serving under the Meiji government, to design the first modern office building in Tokyo’s Marunouchi district, the Mitsubishi No. 1 Building. This was followed by the construction of more three-storied red brick office buildings in the area which came to be known as the “London Block” after its resemblance to the British capital. Mitsubishi Building No. 1 was demolished in 1968 but rebuilt in 2009 as a faithful re-creation of the original structure. It is now known as the Mitsubishi Ichigōkan Museum.

Rebuilt in 2009 as an exact replica of the original Mitsubishi No. 1 Building, this red-brick structure is now a museum. Both the interior and exterior replicate the original construction techniques and materials.

Rebuilt in 2009 as an exact replica of the original Mitsubishi No. 1 Building, this red-brick structure is now a museum. Both the interior and exterior replicate the original construction techniques and materials.

(Originally written in Japanese by the Nippon.com staff. Banner photo: Tokyo viewed from the Skytree in Oshiage, Sumida.)