Who Is the Author of Article 9 of the Constitution of Japan?

Politics Society- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

A Letter from a Class A War Criminal

On December 10, 1945, Shiratori Toshio, former Japanese ambassador to Italy and now a Class A war criminal, finished writing a lengthy letter addressed to Foreign Minister Yoshida Shigeru as he awaited trial in Sugamo Prison. The letter was written in English. This may have been for one of two reasons: to give prison censors the slip or to catch the attention of the occupation authorities. The latter appears more likely.

Shiratori opens the letter with reminiscences of his time as a lecturer on foreign affairs for the emperor in the early 1930s:

That privileged post which I held for nearly three years afforded me the rare opportunity of observing and studying the personality of our Sovereign at a close range. As a result, I could thoroughly convince myself of his innate love of peace, his thirst for truth, and his genuine anxiety for the welfare of his people. Especially keen, I found, were his interest in foreign affairs and his desire for good relations with other nations. It seemed to me that he had an instinctive mistrust of the military and that nothing worse became him than his title of Generalissimo and the military uniform in which he had always to appear in public.

After issuing his declaration of humanity, Emperor Shōwa traveled around Japan to meet and talk with the people, beginning with Kanagawa Prefecture in February 1946. (© Jiji)

After issuing his declaration of humanity, Emperor Shōwa traveled around Japan to meet and talk with the people, beginning with Kanagawa Prefecture in February 1946. (© Jiji)

How truthful was Shiratori in depicting the emperor thus? Was he hoping to convince someone by portraying the emperor in this way? Yoshida must have known Emperor Shōwa up close better than Shiratori. I therefore think this paragraph was intended for the occupation authorities, who had not yet reached a final decision regarding the emperor’s fate—whether he would be prosecuted as a war criminal in the Tokyo Trials (the International Military Tribunal for the Far East), forced to abdicate, or deprived of all rights of sovereignty to remain a constitutional monarch symbolizing Japan and the unity of its people.

Passage on Constitutional Reform

The most interesting part of the letter is its conclusion. Touching on the issue of reforming the Constitution (its complete renewal had not yet come up), Shiratori proposes the inclusion of “provisions containing a solemn promise on the part of the Emperor never, under any circumstances, to make his subjects fight a war, the right of the people to refuse military service in any form under any government, and the non-application to martial use of any part of the resources of the country.” Such provisions, Shiratori writes, “must form the corner-stone of the fundamental law of the new Japan if it is seriously meant to make her a land of eternal peace.” He also adds that the emperor’s “mission to reign over this land in peace and tranquility . . . would be a totally new departure in constitutional legislation.”

Article 9 of the 1947 Constitution of Japan, which states that “the Japanese people forever renounce war as a sovereign right of the nation,” became an innovative clause of global significance. Chronologically, Shiratori’s letter was the first attempt to apply the principle of eternal renunciation of war to the constitution, although similar appeals had already been heard in the Japanese press around September–October 1945, if in the form of people’s wishes.

In the following sections, I will attempt to put the letter in the context of well-known events and historical facts.

Letter’s Deliverer to Occupation Authorities a Mystery

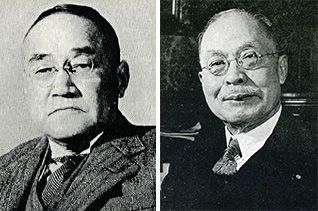

Yoshida Shigeru, left, and Shidehara Kijūrō.

Yoshida Shigeru, left, and Shidehara Kijūrō.

At Shiratori’s request Yoshida Shigeru sent the letter to Shidehara Kijūrō, who headed the Foreign Ministry for many years prior to World War II and became prime minister soon after the war. The letter reached SCAР’s General Headquarters (GHQ) commanded by General Douglas MacArthur no later than January 20, 1946. But it is unknown who delivered the letter—it could have been Yoshida himself—or who actually read it.

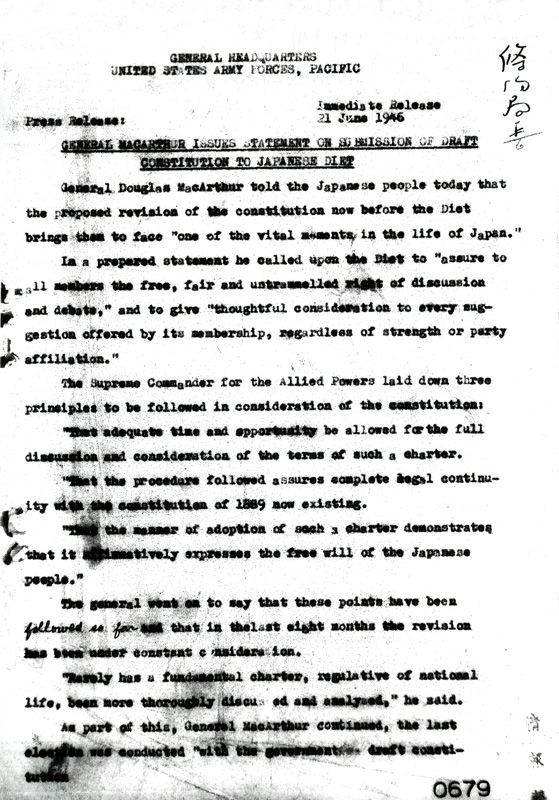

On February 1, 1946, General MacArthur became aware of an outline of constitutional revisions drafted by the Japanese government’s Constitutional Problems Investigation Committee. MacArthur rejected the outline and, on February 3, ordered the GHQ’s Government Section to draft a constitution founded on three basic provisions that he had written himself, known as the MacArthur Notes.(*1) On February 4 Courtney Whitney, chief of the Government Section, gathered his subordinates and instructed them to begin working on a draft constitution, conveying to them MacArthur’s provisions, which included renouncing war as a sovereign right of the nation. The GHQ draft was completed on February 10 and approved by MacArthur on February 12. It was handed over to the Japanese government the next day.

The Government Section made it clear that the emperor and Japanese government had no choice but to accept the draft. Whitney also stated that, if Japan failed to accept, it would be difficult to ensure the fate of the emperor, whom several of the Allied Powers were demanding to put on trial. MacArthur confirmed this politely but firmly in a meeting with Shidehara on February 21.

Debate on the Renunciation of War

The first meeting between Emperor Shōwa and General MacArthur at the US Embassy in Tokyo on September 27, 1945.

The first meeting between Emperor Shōwa and General MacArthur at the US Embassy in Tokyo on September 27, 1945.

The greatest controversy arose over the parts of the GHQ draft regarding the renunciation of war and the emperor’s new status. Justifying the need to declare the renunciation of war, MacArthur told Shidehara, “Japan should take moral leadership by stating clearly that it renounces war.”

“You talk about leadership, but other countries may not go along with Japan,” Shidehara responded.

To this MacArthur said, “Even if no other country goes along, Japan will lose nothing. Those who will not give their support are in the wrong.”

The draft was approved by the emperor on February 22 and released to the public as the “Outline of a Draft for a Revised Constitution” on March 6. In the discussions over the draft, Whitney had insisted that the renunciation of war be given a chapter of its own and not just declared in the preamble as one of the basic principles.

Historians Richard Finn(*2) and Nishi Toshio say the truth regarding how Article 9 came about is shrouded in darkness. According to MacArthur, it was Shidehara who first put forward the idea during a meeting on January 24, 1946. But the Japanese government was still working on its own draft constitution at that point.

Yoshida claimed that Article 9 was formulated entirely under MacArthur’s initiative. Based on MacArthur’s remarks that war should be outlawed, Finn concludes, “The idea of a no-war clause in the Japanese constitution was almost certainly MacArthur’s, and the responsibility for having it inserted was surely his.” Finn evidently knew nothing of Shiratori’s letter.

Shiratori’s Indirect Influence on MacArthur

A Japanese translation of the part of Shiratori’s letter in which he writes about revising the constitution and including in it the renunciation of war was published in 1956 in an article by Hirota Yōji, who served as Shiratori’s defense attorney in the Tokyo Trials. After closely examining every available source, I have concluded that MacArthur must have gotten the idea for Article 9 from Shidehara—MacArthur’s memoir, which touches on this period, was published a full eight years after the Japanese translation of the letter—and that it was more than likely Shiratori who influenced Shidehara in that regard.

In his article Hirota indicated that the renunciation of war was discussed at the January 24, 1946, meeting between MacArthur and Shidehara, four days after Shiratori’s letter was delivered to the General Headquarters, and that there would have been ample time for Shidehara to read it before work on the GHQ draft began. But the article, having been published in an obscure journal, went largely unnoticed.

General MacArthur’s statement regarding the draft constitution, dated June 21, 1946.

General MacArthur’s statement regarding the draft constitution, dated June 21, 1946.

Shidehara could have been inspired by Shiratori’s letter but presented MacArthur with the idea of making renunciation of war a foundation of the new constitution as his own without any mention of Shiratori, a Class A war criminal. The no-war principle resonated with MacArthur, who then focused even more effort on the draft constitution. It is also possible that Whitney either read the letter, which had reached the GHQ, or heard about its contents from a lieutenant at about the same time that MacArthur learned of the idea. It is widely known that Whitney had significant influence on MacArthur in political matters.

All of the above are probably not enough to definitively pin the authorship of Article 9 on Shiratori. Nonetheless, the likelihood of his having been an influence is undeniably large.

I presented this theory at the public dispute on my doctoral dissertation, “Shiratori Toshio and Japanese Foreign Policy (1931–1941),” at the University of Tokyo in 2002. Many participants listened with interest but also with skepticism. They seemed to find too bold the idea that a “war criminal” with a reputation as a militarist ideologue could have proposed the renunciation of war as a basic tenet of the constitution.

I later discussed the theory in greater detail in my 2006 book The Era of Struggle: Toshio Shiratori (1887–1949), Diplomat, Politician, Thinker, which I wrote in Russian.To this day, it is the only book-length biography of Shiratori. The full text of the letter to Yoshida is included in Russian-language collection of Shiratori’s selected writings The Re-awakening of Japan (2008).

(Originally written in Russian and published on April 27, 2015. Banner photo: The Constitution of Japan, kept in the National Archives of Japan. © Jiji.)

II. War as a sovereign right of the nation is abolished. Japan renounces it as an instrumentality for settling its disputes and even for preserving its own security. It relies upon the higher ideals which are now stirring the world for its defense and its protection.

No Japanese Army, Navy, or Air Force will ever be authorized and no rights of belligerency will ever be conferred upon any Japanese force.

III. The feudal system of Japan will cease.

No rights of peerage except those of the Imperial family will extend beyond the lives of those now existent.

No patent of nobility will from this time forth embody within itself any National or Civic power of government.

Pattern budget after British system.

(*1) ^ I. Emperor is at the head of the state.

His succession is dynastic.

His duties and powers will be exercised in accordance with the Constitution and responsive to the basic will of the people as provided therein.

(*2) ^ Richard Boswell Finn, (1917–98) was a historian, an honorary professor at American University, a diplomat with the US State Department, and an expert on the history of Japan-US relations.

Yoshida Shigeru constitution GHQ Emperor Showa General MacArthur Shiratori Toshio Tokyo Trials