The Wansei: History’s Castaways Look Homeward to Taiwan

Politics Society Culture- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

In 1895, the Qing government of China ceded Taiwan and the Pescadores (Penghu) to Japan under the Treaty of Shimonoseki, which ended the Sino-Japanese War of 1894–95. The Japanese government established the Office of the Governor-General in Taipei as an organ of colonial rule, and for the next half-century this outpost of the imperial government ruled over Taiwan and the Taiwanese while investing heavily in modern industry and infrastructure. During that time, Japanese settlers migrated to Taiwan in considerable numbers.

Taiwan’s rapid economic development under Japanese rule was a testimony to the diligence and hard work of the island’s inhabitants. After World War II, Japan forfeited control, and residents of Japanese descent were obliged to leave Taiwan. But the achievements of the colonial period helped support the postwar development of Taiwanese society, and that legacy lives on.

A study group, mainly consisting of elderly people born in the colonial era, meets every month in Taipei to learn and speak Japanese together.

A study group, mainly consisting of elderly people born in the colonial era, meets every month in Taipei to learn and speak Japanese together.

Who Are the Wansei?

While the inhabitants of Taiwan were all considered subjects of the Japanese empire, the colonial government classified them according to their origin. Japanese settlers and their children were called naichijin. Inhabitants of Han Chinese descent were known as hontōjin, while the indigenous Taiwanese were referred to as banjin.

By the end of World War II, there were approximately half a million naichijin in Taiwan, including members of the military. But after World War II, Japan forfeited its territorial claim, and China’s Kuomintang, or Nationalist Party, which took control of the island soon thereafter, repatriated almost all of the naichijin between 1945 and 1949. Although such marriages were uncommon, this included fathers and children of non-Japanese women—these women had the option of moving to Japan with their families.

Back in Japan, these repatriated naichijin became known as Wansei. Although the term literally means Taiwan-born, it was applied to all those of Japanese descent—with the exception of military personnel dispatched to the island—who were in Taiwan at the end of the war and subsequently repatriated. It also encompassed those who were born in Taiwan, traveled to Japan to attend university, for example, and remained there.

Between Two Cultures

A survey carried out in October 1945 by the Office of the Governor-General, then under the control of the US military, determined that the total population of naichijin in Taiwan, excluding Japanese military personnel, was 384,847—200,026 men and 184,821 women divided among 106,201 households. The survey also asked each of these naichijin (except for infants and toddlers) whether they would prefer to return to Japan or remain in Taiwan. Of the 323,269 who responded, 182,260 answered that they wanted to return to Japan, while 141,009 said they wished to remain in Taiwan. Among the respondents, women outnumbered men 168,520 to 154,749. Of the men, a full 67,654 indicated that they preferred to stay in Taiwan.

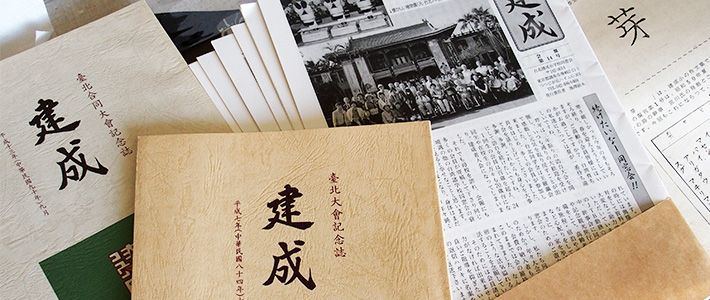

Taiwan-born Tominaga Masaru at home in Tokushima Prefecture. Deeply attached to his native Hualien, Tominaga has spent years researching the city and its inhabitants, amassing an impressive collection of historical materials relating to Taiwan.

Taiwan-born Tominaga Masaru at home in Tokushima Prefecture. Deeply attached to his native Hualien, Tominaga has spent years researching the city and its inhabitants, amassing an impressive collection of historical materials relating to Taiwan.

Of course, they had little access to information and no way of anticipating how things would unfold in either country in the wake of Japan’s defeat. None of them could imagine how their situation would change in the coming years. Some had deliberately turned their back on their birthplace to build a new life in Taiwan, while others had been born and raised in the colony. All must have responded to the survey of October 1945, with a sense of profound anxiety and ambivalence.

The Wansei Then and Now

For some time now, I have been interviewing the surviving Wansei in order to record and preserve their oral history. Although said to be heavily concentrated in Tokyo, the Kansai region, and Kyūshū and other parts of western Japan, the Wansei are actually scattered all over the country.

Regardless of where they live, the Wansei have impressed me as a well-educated and successful community overall. A fairly high percentage are university graduates, and many appear to have done well in their chosen line of work. One reason may be the high quality of their early education in Taiwan. Discriminatory practices placed the naichijin in separate primary schools, which unquestionably gave them educational advantages over their native Taiwanese counterparts—including a better shot at continuing their education.

This sort of discrimination extended to the civil service as well. The government paid a substantial overseas posting allowance to naichijin, resulting in a large wage gap between civil servants of Japanese extraction and their ethnic Chinese counterparts. Although there were certainly exceptions, many of the naichijin families were quite well off, and their children were raised and educated in a relatively privileged environment.

But there is another side to the story as well. Many in the Wansei community stress the difficulties they faced after repatriation and the hard work required just to survive. Most had never even set foot in mainland Japan until then and had to make their way in an unfamiliar environment without local roots or connections. They were often treated as foreigners, particularly in Japan’s provincial towns and cities. Under these circumstances, they naturally gravitated toward one another and formed their own networks. By their own testimony, many of them sorely missed their homes in Taiwan. Through sheer hard work they were able to triumph over adversity, sustained by the memory of their beloved Taiwan.

Families of the fallen gather in Hengchun, Taiwan, in August 2015 for a ceremony honoring Japanese soldiers killed in the Bashi Channel during World War II. They are joined by a number of Wansei and elderly Taiwanese citizens.

Families of the fallen gather in Hengchun, Taiwan, in August 2015 for a ceremony honoring Japanese soldiers killed in the Bashi Channel during World War II. They are joined by a number of Wansei and elderly Taiwanese citizens.

Revisiting the Colonial Past

After decades of autocratic rule, true democracy dawned in Taiwan during the second half of the 1990s, thanks to reforms implemented under President Lee Teng-hui. The years since have seen a surge of interest in local culture and history. At the same time, a more objective assessment of the period of Japanese colonial rule has led to a wider recognition of the positive contribution Japan made to Taiwan’s development.

The elderly Taiwanese citizens who grew up under Japanese rule are known as the “Japanese-language generation,” as they were educated in Japanese and can speak it fluently. Although old age has claimed many of them, they still form a significant sector of Taiwanese society. In the free and democratic climate that has transformed that society over the past two decades, a substantial number of these older Taiwanese have actively and openly embraced the Japanese language as part of their own cultural and linguistic heritage.

Another aspect of this willingness to confront and reassess the Japanese colonial era is the recent surge of interest in the experience of the Wansei.

Hōōboku no hana chirinu (The Flame Tree Blossoms Do Not Scatter) by Imabayashi Toshiharu, now a resident of Fukuoka Prefecture, is a memoir of the author’s childhood in Tainan, where he was born. Since its publication in 2011, this collection of reminiscences has become a highly valued resource for local historians. Tokumaru Satsurō, currently living in Tama, Tokyo, has spent more than 10 years compiling a residential map of Taipei—his hometown—during the era of Japanese rule. Making the most of the Wansei network, he has collected information one piece at a time and gradually incorporated it in a hand-drawn map. It is a mind-bogglingly ambitious task, but the information he has gathered in the process is invaluable for reconstructing the city of Taipei during the colonial period.

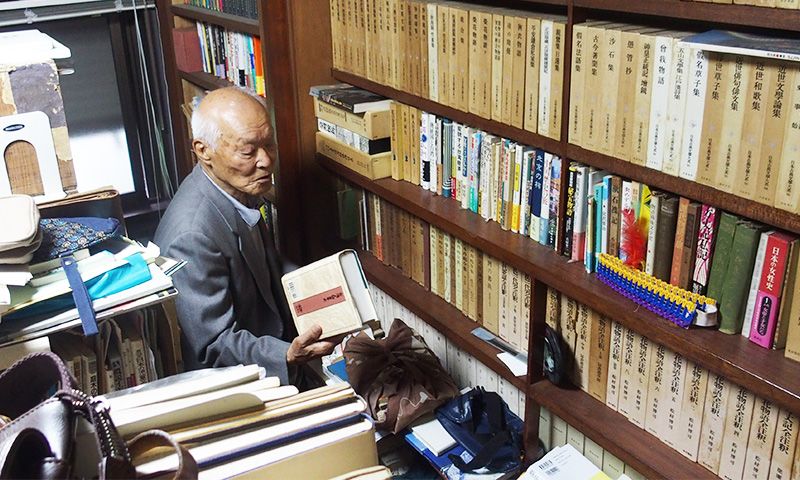

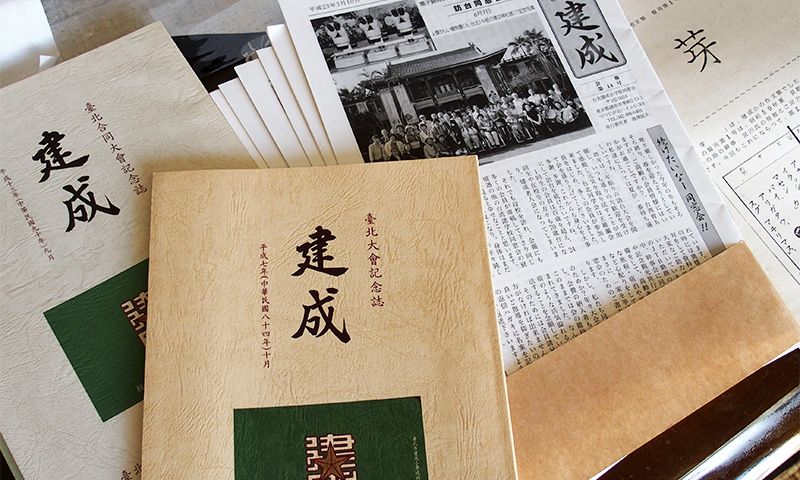

The alumni club of the long-defunct Kensei Elementary School in Taipei continues to publish a newsletter and hold get-togethers.

The alumni club of the long-defunct Kensei Elementary School in Taipei continues to publish a newsletter and hold get-togethers.

Then there is Okabe Shigeru, who has managed the alumni club of his Taipei elementary school with such single-minded diligence that it has remained active to this day. Needless to say, the records of this club also contain precious historical materials. Such efforts reflect the deep attachment of the Wansei for the land where they were born and raised.

The Taiwan Kyōkai (Taiwan Association) is a Japanese organization established in 1951 to promote friendship and communication among Japanese citizens repatriated from Taiwan after World War II. Today the association is involved in a variety of activities, including programs to support Japan-Taiwan friendship. It also collects and houses a wide range of documents and other materials relating to the naichijin and Wansei and makes them available to researchers and other interested persons. In 2015, when events were held around the region to commemorate the 70th anniversary of the end of World War II, Taiwan Kyōkai Director Nei Kiyoshi helped organize and publicize memorial ceremonies to honor the war dead.

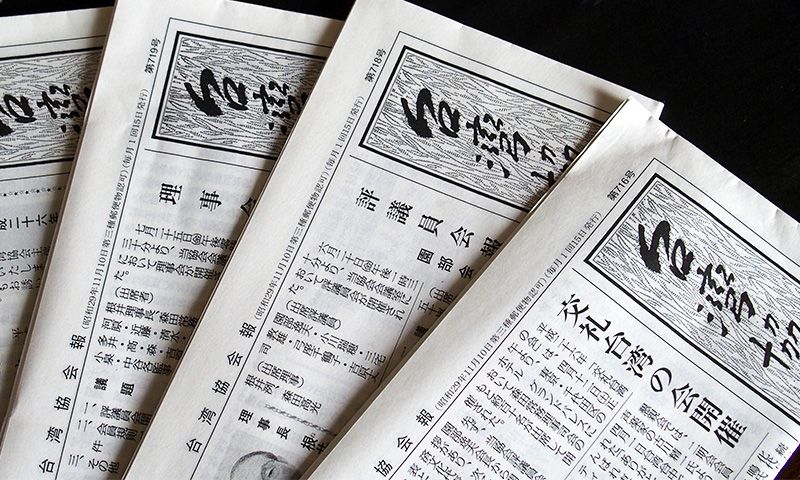

Monthly bulletin of the Taiwan Kyōkai. The association’s library provides access to valuable historical materials and documents.

Monthly bulletin of the Taiwan Kyōkai. The association’s library provides access to valuable historical materials and documents.

One thing almost all the Wansei share in common is an enduring affection for Taiwan. They love Taiwan as much as they do Japan—in some cases, even more—and care deeply about its future. Historian Takenaka Nobuko (a native of Suao township in Taiwan, currently residing in Tokyo), author of a book documenting the lives of Japanese women in colonial Taiwan, puts it succinctly: “We Wansei view Taiwan as our beloved homeland. After Japan lost the war, we were set adrift, but our feelings for Taiwan have not diminished one iota.”

Historian Takenaka Nobuko, a Wansei with an abiding affection for Taiwan, is acknowledged as a leading authority on the local history of her hometown of Suao.

Historian Takenaka Nobuko, a Wansei with an abiding affection for Taiwan, is acknowledged as a leading authority on the local history of her hometown of Suao.

Despite the absence of diplomatic relations between Tokyo and Taipei, social, cultural, and economic exchange between Japan and Taiwan is livelier than ever, with some 5 million people traveling back and forth between the two countries every year. Taiwan has become an increasingly popular destination for the class trips traditionally organized by Japanese high schools, and as many as 30,000 secondary school students were expected to visit the island in 2015. Japanese tourists who visit Taiwan often gush about the experience, dwelling particularly on the kindness and courtesy with which they were received.

On October 16, 2015, Taiwan’s Central Motion Picture Corp. released Wansei Back Home, a documentary produced by Tanaka Mika, author of a book of the same title. Directed by Taiwanese director Huang Ming-cheng, it tells the story of naichijin living in Hualien and the hardships attending their repatriation after World War II. How do younger Taiwanese view these exiled settlers and the legacy of the colonial era? More than seven decades since the end of World War II and Japanese colonial rule, it is time for all of us to revisit and reassess the complex historical relationship between Japan and Taiwan.

(Originally written in Japanese on October 5 and published on October 16, 2015. Banner photo: Seven decades after their repatriation to Japan from Taiwan, the alumni of a Japanese elementary school in Taipei have remained in touch with one another, largely thanks to this alumni bulletin. Photos by Katakura Yoshifumi.)