Behind Japan’s Ratification of the Hague Abduction Convention

Politics Society- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

On May 22, Japan approved a bill to join the Hague Convention on the Civil Aspects of International Child Abduction, a treaty that attempts to address the problem of cross-border parental child abduction.

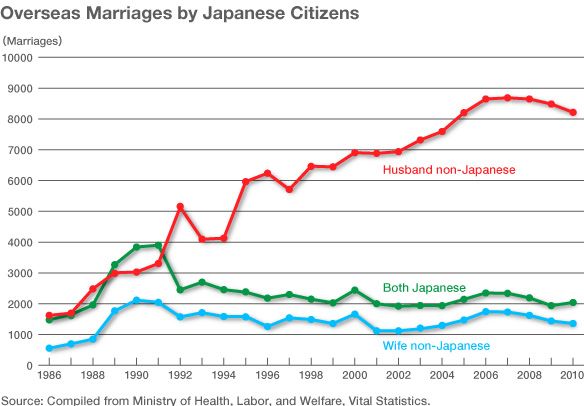

International marriages involving Japanese citizens have been on the rise since the 1980s. The number of Japanese women marrying non-Japanese men overseas has soared since the collapse of the 1980s bubble economy, and so have accusations of international parental child abduction against Japanese mothers. Since around 2005, Japan has been under mounting pressure to sign the treaty from those Western countries where Japanese women are most apt to emigrate and marry.

Drafted by the Hague Conference on Private International Law in 1980, the Hague Abduction Convention mandates procedures for the return of any child wrongfully removed by a parent from one member country to another. Although the convention has 89 signatories as of April 2013, Asia is scantily represented among the contracting states. So far, only Hong Kong and Macau, Singapore, South Korea, Sri Lanka, and Thailand have joined.

Officials in the United States have long seen ratification by Japan and India—Asia’s top “offenders” when it comes to parental child abduction—as vital to further progress on the international abduction issue, as I learned when I took part in a project concerning the Hague Abduction Convention offered in the summer of 2012 under the US Department of State’s International Visitor Internship Program. Now that Japan’s ratification is assured, we must move quickly to build a domestic legal and procedural framework to ensure effective implementation of the treaty, which will apply to Japanese couples living abroad as well as international couples.

The FBI’s Most Wanted Japanese Women

To address the problem of parental abduction by Japanese women, we first need to understand its causes. Why would Japanese women “kidnap” their own children?

To begin with, a Japanese woman may not realize that she is guilty of abduction if she takes her child back to Japan without the father’s consent. Japanese family law differs from family law in the West, where divorced couples are typically granted joint custody on the assumption that society can best serve children’s interests by protecting their relationship with both parents. In Japan, when a couple divorces, the law grants sole custody to one of the parents, most often the mother. This is why the website of the Consulate General of Japan in San Francisco warns that it is a federal crime for a parent to take his or her child away from the other parent without the latter’s consent.

Divorces are relatively common in the United States, and lawyers typically guide the parties through the process. This can lead to bitter court battles, and all too frequently a desperate or angry parent vanishes with the children. While family law differs from state to state, parental kidnapping is a federal crime and is under the jurisdiction of the Federal Bureau of Investigation. Among the “most” wanted lists on the FBI’s website is a Parental Kidnappings page that includes the names and photos of several Japanese women, accompanied by details of their alleged crimes and photos of their child “victims.”

In Japan, by contrast, 90% of all divorces are settled consensually out of court by filing a notification of divorce. Of the remaining 10%, the vast majority are settled by mediation in a family court. Divorces requiring a court verdict are very rare. The mother receives sole custody of the children about 80% of the time, a practice that took hold from the mid-1960s on. A woman raised in a society where mothers receive custody as a matter of course may think it only natural to take her child home with her when her marriage goes bad.

Tough Options for a Double Minority

A second factor behind the relatively high incidence of international abductions by Japanese women is doubtless the challenges they face in negotiating an acceptable divorce settlement. In the United States and other countries, custody issues and other terms are usually negotiated by divorce lawyers. But finding and paying a reputable and reliable divorce attorney cannot be easy for an economically and socially disadvantaged outsider.

Coming from a culture where gender inequality is deeply ingrained to one in which married women are generally expected to have their own careers, Asian women married to American men may not regard themselves as vulnerable or disadvantaged. However, very few of them are able to find good, steady jobs while they are married. If her marriage falls apart, the woman faces the daunting prospect of making her own way in a foreign society, burdened with the double disadvantage of her gender and ethnicity.

Another probable factor behind this behavior is the failure of many Japanese women to build a strong social network in their adopted society.

Most young and middle-aged Japanese women today were brought up in suburban nuclear families, in which the bond between the children and the mother is particularly close. Coming from such a context, a Japanese woman may find nothing particularly disturbing at the outset about her social isolation as a foreign mother left to cope alone with a young child. She is also that much more likely to view her child as her own “property.”

The ability of immigrant women to build ties with the larger community varies greatly according to their individual personality and skills.

Unable to Ask for Help

Another problem is the fact that the Japanese are brought up to view domestic quarrels as “dirty laundry” that should never be exposed to the gaze of outsiders. The average Japanese woman would rarely seek assistance or counseling at a local government or nonprofit agency.

This could turn into a major issue after ratification of the Hague Abduction Convention, which requires evidence in the form of police reports, counseling sessions, and medical records to support claims of domestic abuse or violence. The website of the Japanese consulate in San Francisco urges anyone in such a situation to notify the police immediately and provides other contact information for victims of domestic violence. But the authorities must recognize that, particularly in Los Angeles and other major metropolitan areas where jails and prisons are over capacity, first offenders do not stay in custody for long, and women who report their husbands risk further abuse in retaliation. Language is another issue. Advocates for Japanese victims of domestic violence strongly advise women who have problems communicating in English to secure interpreting services when dealing with the police or other public agencies. Unfortunately, women with this sort of linguistic handicap rarely know how to seek help or support from the advocates and agencies that are there to assist them.

In the preceding, I have outlined the most likely factors motivating Japanese women who remove their children from their country of residence without the father’s consent. Unfortunately, at this point it is difficult to provide any scientific data concerning cases involving Japanese women. Doubtless there will be instances in which a mother has no other recourse than to flee with her child to guarantee the latter’s safety. In those cases, it is essential that she leave evidence of domestic violence with a neighbor, a social service agency, a health care facility, or the police.

Problems on the Other Side

Marital conflicts between Japanese women and their non-Japanese husbands are surely exacerbated in many cases by the fact that the husband has rarely if ever visited the country where his wife was born and raised.

Just as Japanese women tend to assume that the rules of Japanese society prevail everywhere, Western men tend to view the norms of their own society as universal. In the United States, for example, a child born on American soil is regarded as an American. As a result, if a Japanese mother takes her child home with her to Japan, she is treated as having abducted an American citizen, as suggested by the ABC News headline “Abducted to Japan: Hundreds of American Children Taken” (February 16, 2011).

During the aforementioned International Visitor Leadership Program in which I took part, I had the opportunity to meet with several “left behind” American fathers whose children had been taken to Japan. Most spoke very limited Japanese, and several had never even been to Japan. All denied committing any act of violence against their wives. But their quickness to blame Japan unilaterally and their unwillingness to see the Japanese side of the issue attest to the limited nature of their contact with Japanese society and their Japanese in-laws.

Woefully Unprepared

Japan’s ratification of the Hague Abduction Convention is now a certainty, but at this point Japan is woefully ill-equipped to implement the treaty.

In the United States, where child abduction occurs relatively often, the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children was established in 1998 for the express purpose of locating such children. The NCMEC is a nonprofit organization that currently provides data on more than 300,000 missing children, as well as information on child sexual exploitation. It also operates a 24-hour hotline and a cyber-tipline through which ordinary citizens can report suspected illegal activity and sightings of missing children. Information originating from US sources is passed on to competent state and local police authorities. The NCMEC also provides access to its database for investigations by the FBI, the Internal Revenue Service, and the US Postal Inspection Service. In a country with as many immigrants as the United States, a good number of these incidents inevitably involve the transport of children across national borders. To address such cases, the NCMEC has established an international arm, the International Centre for Missing and Exploited Children. Both the NCMEC and the ICMEC have arrangements with Amtrak, Greyhound, and American Airlines to have missing children who are located transported home at no cost.

On request from a Japanese court, the ICMEC will provide information on a child illegally taken to the United States from Japan. But which organization in Japan can play the corresponding role of providing information on a child illegally taken to Japan, and how would one go about providing it to authorities in a foreign country?

According to a related bill outlining the domestic procedures for returning children to their country of residence, the Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs will be the central authority in charge of locating children who have been taken to Japan. Family courts in Tokyo and Osaka will generally handle the cases and make decisions regarding the children’s return. Communication and coordination among national and prefectural agencies will be essential to the process, but many worry that cases will be bounced from department to department and get lost in the Japanese bureaucracy. Under the Hague Abduction Convention, a left-behind parent has just one year to commence proceedings for the child’s return, and courts are required to “act expeditiously.” When I asked one of the family courts about the issue of timely action, I was told that they could not comment because there were no cases to use as a reference.

Visiting the Los Angeles County District Attorney’s Office in 2012 as part of the International Visitor Leadership Program. California Deputy Attorney General Elaine Tumonis is shown seated front and center, with the author standing behind her.

Visiting the Los Angeles County District Attorney’s Office in 2012 as part of the International Visitor Leadership Program. California Deputy Attorney General Elaine Tumonis is shown seated front and center, with the author standing behind her.

During the IVLP program, California Deputy Attorney General Elaine Tumonis gave up part of her summer vacation to talk with participants at the Los Angeles County District Attorney’s office. We also had an opportunity to meet with a family law judge for the Los Angeles Superior Court. We learned that the District Attorney’s office has a child abduction section staffed with investigators, paralegals, and others specializing in such cases. A federal judge explained to us the importance of the international judicial conferences that facilitate information sharing among family law judges in the Hague Convention’s contracting states. One wonders how Japan’s family court judges will acquire comparable expertise and build international partnerships given the frequency of transfers within the Japanese judicial system.

Although the related bill stipulates that Japan can refuse to return a child when there is a risk of spousal abuse, one wonders how a parent is to prove such a danger. What role will attorneys and family court probation officers play? Will the women be forced to bear the costs of mediation, including interpreting services? These are just a few of the questions attending Japan’s ratification of the Hague Abduction Convention. The government and the courts owe it to the people to provide answers.

(Originally written in Japanese on May 2, 2013.)

San Francisco Child abduction Hague Convention Itsuko Kamoto international marriage FBI Consulate General of Japan NCMEC family court Los Angeles County District Attorney’s Office Elaine Tumonis