A Welcome Revision of the Worker Dispatch Act

Politics Economy Society- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

A Highly Peculiar Japanese Law

With the passage of the revised Worker Dispatch Act this year, Japan’s highly unusual law on the dispatch of workers to client companies by staffing service agencies was finally brought into line with the legislation of other advanced countries. The process of enacting this revision was far from smooth, however. Last year the bill submitted by the government to the ordinary session of the National Diet in March was scrapped when the session ended, and the same fate befell the bill submitted to the extraordinary session of the Diet in September. And the bill the government presented to the ordinary session of the Diet in March this year ran into fierce resistance from the opposition; it was not passed until September, as the unusually long session drew to a close (this year’s ordinary Diet session was extended far beyond its usual end to secure passage of the government’s security legislation). And the debate over the revised law (whose full name is “Act for Securing the Proper Operation of Worker Dispatching Undertakings and Improved Working Conditions for Dispatched Workers”), as seen in the positions advanced by opposition legislators and in media commentary, was emotional in tenor and failed to address the essential issues.

Though most scholars of labor law were at least vaguely aware that Japan’s Worker Dispatch Act was highly exceptional in terms of global norms, they did not give voice to this awareness. Laws in other advanced countries concerning the dispatch of workers are labor laws, and their purpose is to protect the workers in question. This may seem only natural, but it is not true of Japan’s law. The Worker Dispatch Act is a business law, and its purpose is to regulate the operations of businesses that undertake the dispatch of workers, a labor practice seen as being fundamentally undesirable. But for whom is the dispatch of workers undesirable? That is the issue.

Protecting the Jobs of Regular Employees

As is clearly set forth in policy documentation at the time when the Worker Dispatch Act was originally adopted in 1985, the dispatch of workers was considered undesirable not for the dispatched workers but for regular employees under Japan’s customary employment system. The greatest legal purpose of the law was the “prevention of substitution for regular employment.” The idea was that regular employees did not want to have “undesirable” dispatched workers invade their workplaces and take their jobs.

In order to prevent this from happening, the approach adopted when the law was enacted was to recognize the use of dispatched workers only for work not included in the scope of the customary system of lifetime employment (under which companies hire new graduates straight out of school and employ them until they reach the mandatory retirement age). The legal rationalization for this approach was based on defining certain job categories as “specialized” or as involving special types of employment management—meaning that the use of dispatched workers for these job categories did not involve substitution for regular employment.

“Specialized” Job Categories Under the Worker Dispatch Act Before the 2015 Revision

| 1985 Enacted (13 categories) | 1986 Revised (16 categories) | 1996 Revised (26 categories) | 2002 Revised (26 categories) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Software development | Software development | Software development | Software development |

| Operation of business equipment | Operation of business equipment | Operation of business equipment | Operation of business equipment |

| Interpretation, translation, and stenography | Interpretation, translation, and stenography | Interpretation, translation, and stenography | Interpretation, translation, and stenography |

| Secretarial work | Secretarial work | Secretarial work | Secretarial work |

| Filing | Filing | Filing | Filing |

| Market research | Market research | Market research | Market research |

| Financial processing | Financial processing | Financial processing | Financial processing |

| Business document preparation | Business document preparation | Business document preparation | Business document preparation |

| Demonstration of machinery | Demonstration of machinery | Demonstration of machinery | Demonstration of machinery |

| Tour conducting work | Tour conducting work | Tour conducting work | Tour conducting work |

| Reception and guide services, parking management | Reception and guide services, parking management | Reception and guide services, parking management | Reception and guide services, parking management |

| Building cleaning work | Building cleaning work | Building cleaning work | Building cleaning work |

| Operation, checking, and maintenance of building equipment | Operation, checking, and maintenance of building equipment | Operation, checking, and maintenance of building equipment | Operation, checking, and maintenance of building equipment |

| Machinery design | Machinery design | Machinery design | |

| Operation of broadcasting equipment | Operation of broadcasting equipment | Operation of broadcasting equipment | |

| Production of broadcast programs | Production of broadcast programs | Production of broadcast programs | |

| Research and development | Research and development | ||

| Planning of the development of business operation systems | Planning of the development of business operation systems | ||

| Production and editing of books | Production and editing of books | ||

| Advertising design | Advertising design | ||

| Interior coordinators | Interior coordinators | ||

| Announcers | Announcers | ||

| OA instructors | OA instructors | ||

| Sales engineers | Sales engineers, financial product sales | ||

| Stage sets and props designers and coordinators for broadcast programs | Stage sets and props designers and coordinators for broadcast programs | ||

| Telemarketing sales | Telemarketing sales |

Source: Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare, Study Group on the Future Shape of the Worker Dispatching System, First Round (October 17, 2012), “Rōdōsha haken seido no genjō” (Present State of the Worker Dispatching System). English translations from “Act for Partial Revision of the ‘Act for Securing the Proper Operation of Worker Dispatching Undertakings and Improved Working Conditions for Dispatched Workers,’ (The Revised Worker Dispatching Act)” MHLW 2012, with editorial revisions by Nippon.com.

Note: Pink highlighting marks additions made under revisions to the law.

In fact, though, the bulk of these “specialized” job categories opened to use of dispatched workers involved clerical and secretarial work performed by OLs (“office ladies”), as female office workers are called in Japanese. “Filing,” a vague category that does not appear in the Japan Standard Occupational Classification, became the most common type of “specialized” job for which workers were dispatched under the law. And “operation of business equipment”—a basic skill for office employees—later came to be widely used as a supplementary category for worker dispatching. This is how the logical gap between the idea of dispatching workers to do specialized jobs and the reality of worker dispatch activities was papered over.

The reason this ruse was publicly accepted was that, at the time of the law’s enactment, OLs were tacitly expected to work for a relatively short period, from when they graduated to when they got married; for this reason, replacing them with dispatched workers was not seen as substitution for regular employment. As long as the permanent jobs of the “salarymen” (regular male employees, called sararīman in Japanese) were preserved, it did not matter how many OLs might be replaced with dispatched workers. And in order to maintain this duplicitous arrangement, nobody objected to legal provisions that forbade the dispatch of males performing highly specialized jobs, which were not classified as “specialized” work under the law, while allowing the dispatch of increasing numbers of females performing ancillary tasks, which were conversely classified as “specialized”.

The 1999 Revision: A Missed Opportunity for Fundamental Reform

There was one opportunity for a fundamental overhaul of this duplicitous and internationally peculiar Worker Dispatch Act, namely, at the time of the 1999 revision of the law in connection with Japan’s ratification of the International Labor Organization’s Private Employment Agencies Convention (no. 181). I was present for the procedures that led to the approval of this convention at the ILO’s general conference in 1997, and having directly witnessed the discussions among representatives of government, workers, and employers, I expected that the Japanese law would be revised in line with the thinking incorporated in this new convention. Unfortunately, though, this did not happen. The peculiar Japanese notion of preventing substitution for regular employment was left unchanged, and the fiction that worker dispatch, being limited to “specialized” jobs, did not involve such substitution was allowed to stand.

Under the 1999 revision, the scope of worker dispatching, which had previously been limited to specialized jobs, was extended to cover ordinary work, subject to a limitation on the period of dispatch. (Some types of work were excluded from this extension, such as construction, security services, and the jobs of doctors, nurses, and pharmacists.) The law had previously protected regular employment with its limitation on the types of work that could be handled by dispatched workers; the 1999 revision supplemented it by restricting the period of dispatch for ordinary work, for which dispatched workers could more easily substitute for regular employees, as an additional guard against such substitution.

The logical incoherence of this peculiar set of provisions was revealed by the 2009 Supreme Court ruling on the Iyo Bank case. When ordinary employees with a fixed term of employment have their terms repeatedly renewed, they can gain a sort of “tenure” on their jobs, meaning a restraint on their employers’ ability to let them go by not renewing their terms. But the top court ruled that dispatched workers could not expect to gain this sort of job stability, since the Worker Dispatch Act, which aimed to prevent substitution for regular employment, did not envisage such an outcome. The ruling required employers to discriminate in favor of directly employed fixed-term workers over dispatched workers. The case was subsequently submitted to the ILO, which issued its own recommendations on the matter.

Dropping the Fiction of 26 “Specialized” Job Categories

This year’s revision of the Worker Dispatch Act was based on a report issued by a study group in the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare that for the first time called for partial abandonment of the peculiar Japanese notion of preventing substitution of dispatched workers for regular employees. The report referred to the aforesaid Supreme Court ruling, under which dispatched workers were considered not to be entitled to protection of their expectations for continuing employment, and declared, “It has become clear that there are cases in which the intent of the Worker Dispatch Act to prevent substitution for permanent employment is not consistent with protection of dispatched workers.” The group proposed elimination of the fictitious concept of 26 “specialized” job categories open to worker dispatching, something that I had been advocating for some time.

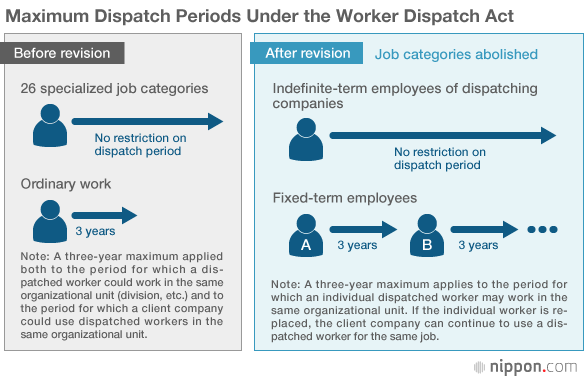

The revision that was submitted to the Diet following further consideration by a tripartite council eliminates the restriction on the period of dispatch for workers employed by dispatching companies for an indefinite term. It sets a three-year limit in principle for the use of dispatched workers by client companies, with the imposition of a three-year maximum on work at the same organization (such as a division) within the client company. But it provides for a somewhat complex framework that allows for extension of the three-year period if the dispatched worker is replaced with another one, subject to consultation with a majority labor union or other majority representative.

Equal treatment of dispatched workers and directly employed workers, which, like equal treatment for part-time and fixed-term-contract workers, is mandatory in European countries, is still just something that dispatching agencies must make “efforts” to achieve even under the revised law. But a Diet-member-initiated bill enacted at the same time, the so-called Equal Pay for Equal Work Act, calls for the necessary measures to be taken in this connection within three years.

A First Step to Legal Protections for Dispatched Workers

Though the revised law is woefully lacking in terms of enforcing equal treatment of workers and promoting the use of systems like labor unions or employee representatives for collective labor-management relations, and it falls short on a number of other details, it is correct in its basic orientation, namely, a switch to legislation based on globally shared principles. Unfortunately, however, there was virtually no recognition of this to be found either in the Diet deliberations or the media commentary on the subject.

What we did hear was complaints that allowing those employed by dispatching companies for an indefinite term to be dispatched for periods longer than three years in the case of “ordinary” jobs (though these include some types of work commonly considered to be highly specialized, such as medical-care-related jobs) would mean “lifetime dispatch,” along with cries that it was terrible to impose a maximum of three years on the previously unlimited period for dispatch of workers for “specialized” jobs (which, as we noted above, refers in practice largely to the clerical and secretarial work of OLs), because this betrayed the expectations of such workers that they could stay on longer. Though it is logically possible to argue in support of each of these criticisms, the critics seemed not to notice that it is contradictory to advance both at the same time.

Be that as it may, the enactment of the revised Worker Dispatch Act has finally swept away the previous focus on preventing the use of dispatched workers to substitute for regular male employees, and it marks a first step toward protection of dispatched workers. Next, the issue of equal treatment will need to be addressed during the three-year period set by the Equal Pay for Equal Work Act. We can also expect to see the policy agenda include the issue of how to involve labor unions or other employee representatives in collective labor-management relations.

(Originally written in Japanese and published on November 5, 2015.)▼Further reading

Addressing the Problems with Japan’s Peculiar Employment System Hamaguchi Keiichirō Addressing the Problems with Japan’s Peculiar Employment System Hamaguchi Keiichirō |  Japan’s Employment System in Transition Genda Yūji Japan’s Employment System in Transition Genda Yūji |