Taking Stock of Suicide in Japan

Society- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

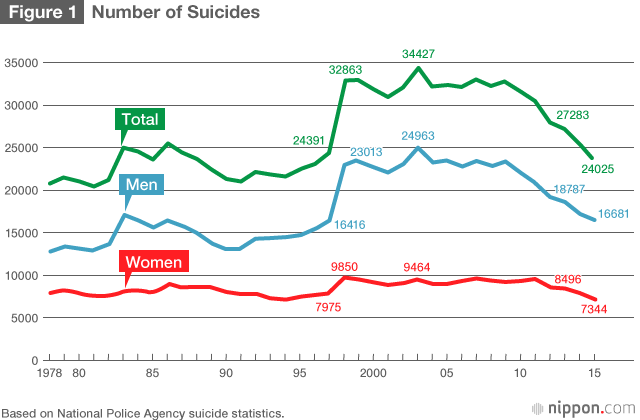

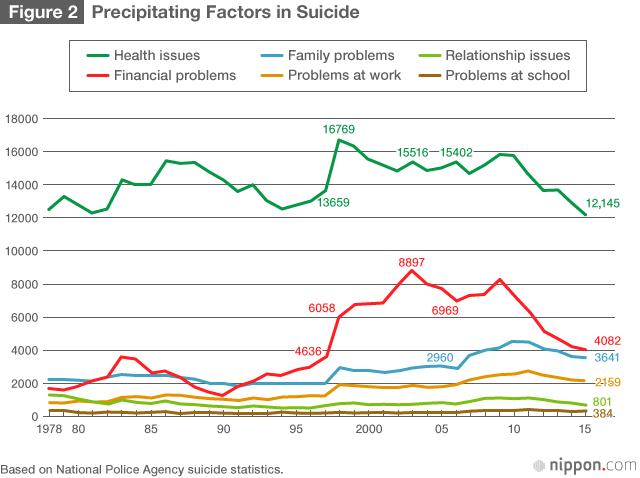

Japan has long had one of the highest suicide rates in the world. According to National Police Agency statistics, the number of Japanese who chose to end their own lives sharply rose from 1998, climbing to over 32,000 from an annual average of 22,000 suicides over the preceding 10 years. The suicide rate stayed above 30,000 for more than a decade, peaking at 34,427 in 2003 before eventually falling below 28,000 in 2012. While figures are now on a downward trajectory, suicide remains one of the top ten causes of death in the country.

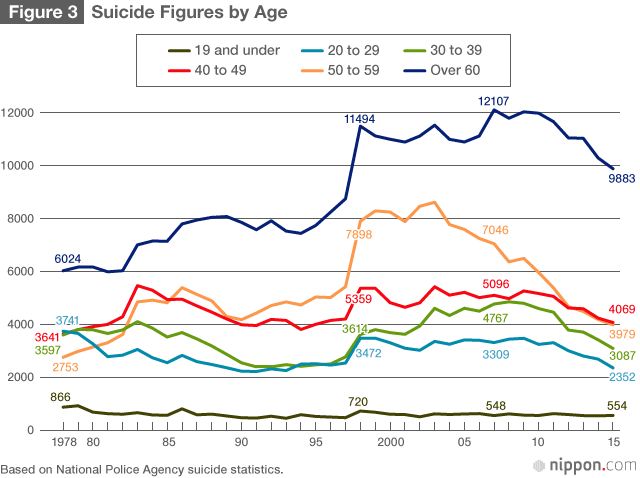

Suicide has been most acute among men in their forties and fifties. Figures surged for this group following the bursting of Japan’s economic bubble in the late 1990s and have remained high through the subsequent years of slow growth.

In the Prime of Life

Experts have struggled to understand this trend in the light of global data showing young men, not their middle-aged counterparts, as being most susceptible to rapid social change. Psychiatrist Amakasa Takashi points to three factors for this anomaly.

- The collapse of Japan’s lifetime employment system: Japan’s postwar “economic miracle” was in great part due to the efforts of loyal workers who spent their entire careers at a single company. The prolonged period of economic stagnation in the 1990s, known as the “lost decade,” though, forced many firms to lay off employees to stay afloat and to abandon the practice of lifetime employment.

- A shift toward performance-oriented employee assessment and compensation: As corporate profits dwindled in the 1990s Japanese companies traded traditional seniority-based wage practices for merit-based compensation systems common at Western firms. This push to bring down labor costs, however, left many employees feeling like they had been treated unjustly.

- Greater reliance on nonregular employees: As Japan’s economy stagnated, companies increasingly turned to nonregular staff, such as part-time and contract employees, to round out their workforce. The stress of having to work for lower wages and with less job security has taken an especially heavy toll on the emotional well-being of middle-aged men.

Shedding Light on the Problem

Japan has traditionally considered suicide to be a personal issue. However, as the number of people taking their lives increased, the Japanese government began to recognize it as a social problem. In 1996 it passed legislation promoting suicide prevention efforts and began rolling out programs the following year. These included initiatives bolstering mental healthcare, helping people suffering under heavy debt, and supporting surviving family members.

These and other efforts have helped to bring Japan’s suicide rate down to its pre-1998 level. In 2015 there were 24,025 suicides, and preliminary figures for 2016 show a continuation of this downward trend. While the decline is a heartening, the fact remains that Japanese remains nearly six times as likely to die by their own hand than in a traffic accident and illustrates that significantly more needs to be done to bring down the suicide rate.

On the Mental Healthcare Front

Experts stress two principles in suicide prevention that focus on overall mental health.

- Early recognition: Suicide can stem from an array of issues, including economic problems, personal issues, and mental disorders. The first step is to quickly recognize the signs of suicide risk.

- Support: Ups and downs are a part of life, but it is important to help people understand they are not alone. It is also necessary to let people can know where to find the appropriate support organizations for their needs.

Self-Imposed Seclusion

Isolation is a major watchword for people at risk of suicide. Individuals suffering from depression or mental disorder frequently feel alone and that there is no one who understands what they are going through. Their feelings of solitude often compel them to withdraw from family members, friends, colleagues, and others who might otherwise be able to provide support. This separation frequently stems from feeling of worthlessness, guilt, or that the world would be better off without them.

Recognizing these signs is vital to preventing suicide. In such circumstances it is imperative that friends, family, and others quickly acknowledge the person’s veiled cries for help and make every effort to reach out and reaffirm their relationship with the individual.

Even in an increasingly interconnected world people are disinclined to look for help in dealing with financial, personal, and other problems. Individuals most at risk of suicide generally suffer from what one clinician termed psychological tunnel vision, where they come see their problems as unsurmountable and see suicide as the only way out.

It is nearly impossible for someone overwhelmed by their troubles to come up with a rational solution on their own. Talking to others is crucial. It may not immediately lead to an answer, but discussing the problem helps ease the person’s mind and enables them to reevaluate their situation more objectively.

Toward Greater Preventative Measures

Government legislation has encouraged suicide prevention efforts nationwide. Ideally, organizations work should together to share information and incorporate new and differing approaches based on effectiveness. However, there have emerged cases of groups pushing their own approaches on others. A certain degree of friction may be unavoidable when rolling out any new initiative, but I hope these groups will overcome their differences and focus on the job at hand.

Significantly lowering Japan’s suicide rate requires the close, coordinated efforts of a wide array of stakeholders. Groups must rally around the common goal of bolstering suicide prevention, focusing on their individual fields of expertise while actively cooperating with counterparts in different areas.

Educating Children About Suicide

Around 300 children under 18 years old kill themselves each year in Japan. Efforts to educate youth in suicide prevention, however, remain inadequate. There are numerous methods used abroad that policymakers in Japan can look to, including the ACT suicide prevention program used at schools in several US states. Standing for “acknowledge,” “care,” and “tell a trusted adult,” the initiative addresses the two principles of suicide prevention mentioned above by teaching children and young adults to recognize symptoms of depression and suicide while also encouraging them to ask for help.

Teaching children to identify risk factors and motivating them to seek support when confronting life’s challenges are positive mental health habits that will serve them far into adulthood. From this standpoint, implementing suicide prevention education early on not only is critical to protect the lives of young people but will also have the long-term benefit of reducing suicide when they reach middle age.

People who feel isolated often turn to suicide to escape the uncertainty of facing the world alone. The first step in suicide prevention, then, is to recognize the warning signs and reach out to those in need. Japan must create a society where people turn an attentive ear to cries for help and strive to face the issue of suicide head on.

(Banner photo: Windows along a hallway at a housing complex in Takashimadaira were installed with bars to prevent people from committing suicide by jumping. © Jiji.)