Fair Play in Short Supply: Japan’s Amateur Sports Scandals Highlight Need for Better Governance

Society- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Harassment a Growing Risk

Japan has seen a string of amateur sports scandals just as preparations for the 2020 Tokyo Olympic and Paralympic Games shift into high gear. The hierarchical structure of national sports bodies are a major factor in the rise of these incidents. Governing organizations hold sway over athletes who, desperate to make the final cut for the games, are wary of blowing the whistle on coaches for inappropriate behavior.

Unequal relationships are breeding grounds for abuse, and as the clock ticks toward 2020 we are likely to see more incidents of violence and harassment. Even as social awareness of these issues grows and society embraces a greater diversity of values, the rigid structure of Japan’s amateur sports authorities prevent these organizations from changing with the times.

Understaffed and Underfinanced

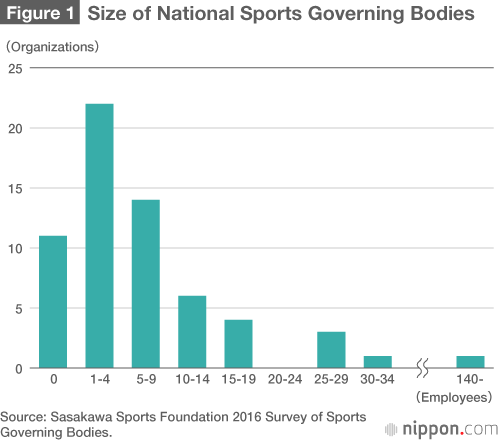

Japanese amateur sports governing bodies are generally small and poorly funded. A 2016 survey of 62 authorities conducted by the Sasakawa Sports Foundation found that 75% of them were minimal operations with 10 or fewer employees. Among these, 11 organizations had no regular employees, 22 had up to 5, and 14 had up to 10.

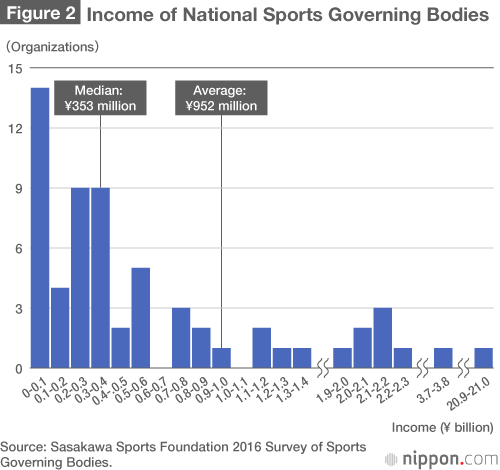

Looking at revenue, the survey also found the average annual income of organizations to be ¥952 million; however, the median income level was just ¥353 million, with 14 groups bringing in less than ¥100 million a year. Understaffed and operating on a shoestring, most organizations struggle to carry out their various duties that include organizing domestic competitions and sending teams to events overseas. Under such conditions, sports bodies are ill-equipped to introduce governance measures to prevent scandals from occurring.

Toughness as a Virtue

Japanese amateur sports authorities suffer from a variety of structural issues.

First, they tend to be excessively hierarchical. At the top are the leaders, who wield the authority to choose who represents Japan in international competitions; they are followed by coaching staff, and then on the lowest rung by the athletes themselves.

This top-down approach has produced a sports culture where the chief goal of organizations is winning international titles. Athletes are expected to be fully compliant with coaching staff, who in singular pursuit of championships resort to strict training practices that can easily cross the line into abuse or harassment.

National sports organizations tend also to be highly collectivist. Members are expected to adhere to set standards of conduct meant to sustain the prestige and identity of the sport. Individuality is not generally rewarded, and athletes who do not want to risk being ostracized and see years of hard work go to waste learn to toe the line.

Finally, sports bodies commonly select administrators not by their managerial ability but by their success as athletes. This practice of hiring based on past glory instead of executive know-how is largely why sports governance in Japan remains so low.

These peculiarities have their roots in the 1964 Tokyo Olympics—they could even be considered a legacy of the games—and have been a feature of amateur sports organizations for so long that few Japanese even question them. Coming a mere 19 years after the end of World War II, the Tokyo Olympics were an opportunity for Japan to affirm its return as a global power and to rebuild national pride by defeating on the field of play former wartime foes. Victory was the top priority, and coaches who steered athletes to the medal podium with hard training won acceptance for their heavy-handed approaches, helping establish a linear structure as the standard for amateur sports in Japan.

After more than five decades, the situation is only now beginning to change as Tokyo prepares for its second summer games. Japanese media outlets have used the recent spate of scandals to criticize how amateur sports organizations are managed. Coverage, though, has mostly focused on individual cases and organizational issues common across amateur sports in Japan and has not delved into the weak governance practices that are the root cause of the incidents.

Amateur Sports Scandals in 2018

| January | |

| Kayaking | A male sprint kayaker was expelled from the sport for spiking a competitor’s drink with a banned substance during the national championships the previous September. |

| February | |

| Speed skating | A male short-track speed skater received a one-year suspension for failing a doping test. |

| April | |

| Wrestling | The head of athlete development at the Japan Wrestling Federation steps down after admitting to harassing Olympic champion Ichō Kaori. |

| Badminton | The former coach of a leading female badminton team is found to have pocketed players’ winnings. |

| May | |

| Swimming | A top male swimmer is suspended from the sport and kicked off the team for the summer Asian Games in Jakarta after failing a doping test in March. |

| American Football | A Nihon University American Football player puts an illegal hit on the quarterback of rival Kwansei Gakuin University during a league game. In July, the university dismisses the coaches for ordering the tackle. |

| August | |

| Boxing | The president and board of the Japan Amateur Boxing Federation resign following allegations of fraud. |

| Kendō | Iaidō officials admit to accepting bribes from candidates facing rank promotion tests. |

| Gymnastics | The Japan Gymnastics Association expels a male coach for physically abusing a female Olympic gymnast. |

| Basketball | Four players on the Japanese national basketball team are sent home and slapped with a one-year suspension for paying for prostitutes during the summer Asian Games. |

External Evaluation Needed for Better Governance

Ideally, national sports authorities would recognize the need for strong governance and have measures in place to identify and address questionable practices and structural problems. In reality, though, organizational blind spots make it difficult to effect change internally. To make matters worse, sports bodies, many of which are not well organized to begin with, are stretched to the limit preparing for the Tokyo Games. Failing to address the issue of governance increases the risk that other Japanese athletes will get caught up in scandals.

The Tokyo Olympics and Paralympics will be a high point for amateur sports in Japan, but there is a real possibility that even if the games are a rousing success, momentum will wane severely afterward. To avoid this fate, national sports bodies need to take concrete steps to bolster their governance practices. It is imperative that the legacy of Tokyo’s second Olympics not just be fancy new stadiums and refurbished infrastructure, but also include lasting ethical and structural change in Japanese amateur sports.

Many experts who recognize the difficulties sports authorities face in reforming from within promote independent evaluation by third-party agencies as a means for improving governance. However, government oversight is already a standard feature in many aspects of Japanese society and could be extended to the realm of amateur sports. Just as the Fair-Trade Commission regulates economic competition and the School Education Act requires universities to be audited by Education Ministry–certified independent organizations at least once every seven years, the government could with minimal difficulty establish systems based on these models to regulate sports organizations.

In fact, efforts along these lines are already underway. In 2017 the Japan Sports Agency conducted a survey on sports compliance efforts as part of its goal of developing a standardized evaluations system for governing bodies. Documenting compliance activities in Japan provides a valuable resource for establishing a new watchdog organization, although public debate is needed to decide if the government should be the one providing such oversight. If the autonomy of sports bodies are to be given precedence, then a system similar to that for universities—relying not on government agencies, but on government-certified, independent evaluation organizations—could be introduced.

The Civil Society Organization Model

Another approach is to have civil organizations evaluate the activity of sports bodies. An example of this can be found in Korea, where a civil organization was launched in 2002 to ensure that junior-high-age female swimmers would continue receiving a proper education. This group has gone on to assess the activities of organizations like the Korean Sports and Olympic Committee, earning public praise for its activities and gaining a degree of influence over government sports policy.

Another instance can be found in Canada. The Respect in Sport program provides online video training to coaches, parents, and others involved in sports activities to help them recognize inappropriate behaviors like bullying, discrimination, and harassment. Founded in the wake of a series of sexual abuse scandals involving youth ice hockey coaches, the program has as its primary aim protecting young athletes and promoting sportsmanship. Organizations that complete Respect in Sports training can display the program logo, and since 2011 all ice hockey coaches in Canada are required to participate.

I urge the authorities in Japan to use the 2020 Tokyo Olympics as an opportunity to establish similar civil initiatives to bolster sports governance and demonstrate Japan’s commitment to fair play. These efforts will benefit not only amateur athletics but society as a whole.

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: Japan Amateur Boxing Federation President Yamane Akira talks to reporters in Osaka on August 7, 2018, following an emergency board meeting of the organization. He stepped down the following day. © Jiji.)