Olympus Endoscopes: The Inside Story

Science Technology Society Lifestyle- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Rapid Strides in Endoscopic Treatment

Having a camera inserted into a bodily orifice isn’t most people’s idea of a good time. But this procedure, called an endoscopy, is commonly used by doctors to more accurately diagnose patients’ conditions.

A lens, a CCD image sensor, and two lights lie at the end of the endoscope. Two lights are used to prevent tools protruding from the end of the endoscope from casting a shadow. Tools are inserted into a channel that can also be used to suck fluids out of the patient.

A lens, a CCD image sensor, and two lights lie at the end of the endoscope. Two lights are used to prevent tools protruding from the end of the endoscope from casting a shadow. Tools are inserted into a channel that can also be used to suck fluids out of the patient.

Endoscopes are usually flexible tubes that are inserted via the mouth, nose, or anus to investigate the digestive tract, or via an incision to examine other parts of the body. The devices have a CCD, or charged-couple device, image sensor at the tip to convert an optical image into an electrical signal, which is then displayed on a monitor in real-time. This is called the video scope system.

Diagnosis is not the only function that endoscopes can perform. “Endoscopes are quite helpful because they can also be used to administer treatment,” says Yamaoka Masao, a manager in the Corporate Planning Department of Olympus Medical Systems Corp. The company holds a 70% global market share in medical endoscopes.

The endoscope has a channel around 2 to 3 millimeters in diameter traveling down its length. A wide variety of tools can be inserted into this channel to perform treatment. Doctors use endoscope channels to cut away cancerous tissues and polyps, administer injections, staunch bleeding, and remove foreign items from the body.

Due to the development of endoscopes and treatment tools, and thanks to the increased skill of medical practitioners, endoscopy treatment has progressed rapidly in recent years. Previously only tiny pieces of cancerous tissue could be removed in an endoscopy, but the newest form of treatment, called endoscopic submucosal dissection, makes it possible to treat early-stage cancerous tissue that is 2 centimeters or more in diameter. Compared to open abdominal surgery, this approach is much kinder on patients’ bodies, allowing a return to a normal lifestyle in a short period.

ESD is the latest method of surgery performed with endoscopes. Previously, EMR (endoscopic mucosal resection) procedures used a lasso-shaped tool to cut away tumors, but could only deal with growths below a certain size. By using a small scalpel, doctors can use ESD to excise tumors larger than 2 centimeters. In Japan, around one in four stomach cancer patients are already receiving this treatment. Source: “Gan o kirazu ni naosu naishikyō chiryō ESD ga wakaru hon” (Understanding ESDs: A Procedure for Treating Cancer Without Major Surgery) (Kōdansha, 2011).

ESD is the latest method of surgery performed with endoscopes. Previously, EMR (endoscopic mucosal resection) procedures used a lasso-shaped tool to cut away tumors, but could only deal with growths below a certain size. By using a small scalpel, doctors can use ESD to excise tumors larger than 2 centimeters. In Japan, around one in four stomach cancer patients are already receiving this treatment. Source: “Gan o kirazu ni naosu naishikyō chiryō ESD ga wakaru hon” (Understanding ESDs: A Procedure for Treating Cancer Without Major Surgery) (Kōdansha, 2011).

An Intellectual Property Hotbed

The video scope system primarily consists of a unit that sends light to the end of the endoscope, a video processor that takes the images from the CCD and displays them on the monitor, and other components. Xenon lamps, a particularly powerful light source, are used to get a clear picture from the dark spaces inside the body.

The video scope system primarily consists of a unit that sends light to the end of the endoscope, a video processor that takes the images from the CCD and displays them on the monitor, and other components. Xenon lamps, a particularly powerful light source, are used to get a clear picture from the dark spaces inside the body.

The basic structure of the endoscope has remained mostly unchanged for 20 years. Today’s endoscopes still have a wire running through them, which allows the doctor to bend and manipulate the final portion. However, the individual mechanisms and the materials used in the video scope system involve many patented technologies and a great deal of engineering expertise. Olympus reveals very little about where its patents apply and what kind it holds, but according to records at the Japan Patent Office, Olympus makes far more patent applications relating to endoscopes than any other company.

Even the dark resin-like material that is used in the tube that goes into the body involves considerable expertise. “If the inserted portion of the endoscope is soft and thin, the procedure is gentler on the patient, but if it is too soft, it can be difficult to insert and maneuver,” explains Yamaoka. “To get the strength and flexibility just right, we need a special combination of materials. And of course, these materials also need to be safe for the human body.”

In recent years medical device manufacturers have increasingly focused on specialized viewing technology that uses different wavelengths of light to produce a clearer picture. Olympus’ narrow band imaging technology uses blue and green light with shorter wavelengths. Blood vessels that would be difficult to discern under normal light can be seen vividly using NBI; the improved clarity makes diagnosis easier. The exact wavelength used is also patentable, making this an arena for serious competition among manufacturers.

NBI Technology: Bringing the Picture into Sharp Relief

With normal light, the blood vessels are drowned in the pink color of the internal organs, making them more difficult to discern (left). Blue light (415 nanometer wavelength) and green light (540 nanometers) make the blood vessels much easier to see. (Photos: Kawamura Takuji, Department of Gastroenterology, Kyoto Second Red Cross Hospital.)

With normal light, the blood vessels are drowned in the pink color of the internal organs, making them more difficult to discern (left). Blue light (415 nanometer wavelength) and green light (540 nanometers) make the blood vessels much easier to see. (Photos: Kawamura Takuji, Department of Gastroenterology, Kyoto Second Red Cross Hospital.)

Decoding Professional Feedback

The doctors who use endoscopes can be very particular about the tiniest details, from the smoothness of insertion to how the scope bends when force is applied. In ESD procedures, for instance, the doctor operates the tiny tools at the end of the endoscope while looking at a monitor. The tools are applied to soft internal organs, so extremely delicate, highly precise movements are necessary. If the endoscope does not function exactly as the operator expects it to, the patient may suffer organ damage. Doctors therefore demand high precision and sensitivity.

When doctors evaluate an endoscope for its ease of use, they can sometimes use rather abstract phrases, like “It feels a little weak when I move the endoscope.” The challenge for engineers is to interpret the doctors’ statements correctly and reflect the desired changes in the instruments. “Understanding user input and reflecting that feedback into the final products is what Japanese makers do best,” says Yamaoka. “The requirements can be varied, but we’re working hard to make endoscopes that are easy to use under all conditions.”

Doctors also demand high-quality images from the endoscope’s camera. This worked in Olympus’s favor, according to Yamaoka: “US manufacturers led the pack at first in video scope technology. One of the reasons that we managed to overtake them was our effective response to doctors’ wishes for clearer images to help them find abnormalities.” For example, if the doctor wants to closely examine the condition of red blood vessels in an internal organ that is pink, a delicate balance of colors is the key, as shown in the NBI images here. What is more, the image quality needed in an endoscope differs considerably from that found in consumer digital cameras; engineers have fine-tuned the quality of endoscope imagery over the years to make the instruments better aids for doctors in spotting abnormalities quickly and administering the correct diagnosis and treatment.

Steady and Gradual Improvement

No matter what they make, the strongest companies focus not only on functionality but also ease of use. When it comes to professional tools, many users will not switch from a company they are comfortable with—even if competitors offer more features and better prices. Yamaoka says, “I don’t think that sudden, ground-breaking change is possible in the digestive endoscope business. At Olympus we intend to continue doing what we’ve been doing, which is to implement steady and incremental improvements to the level of development and manufacturing.” Applying this approach diligently over their 60-year history has rewarded the company with the top share it enjoys today.

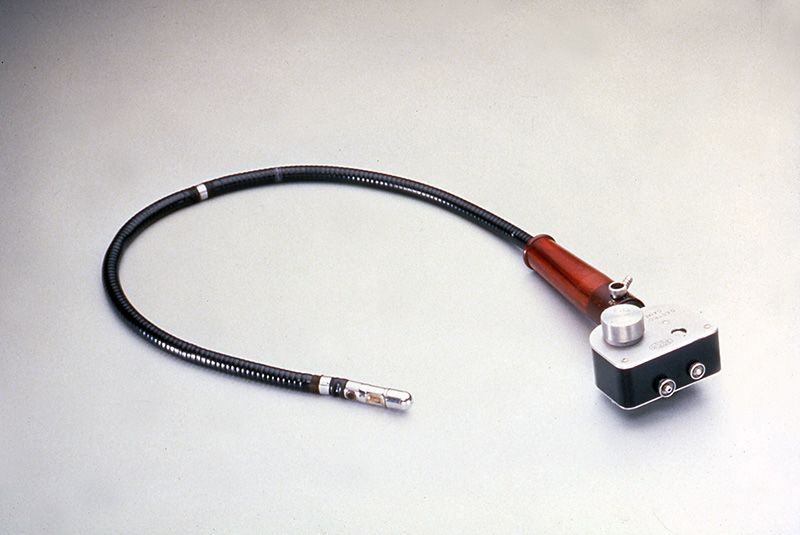

The 1950s Endoscope

The beginnings of Olympus’ efforts in the endoscope market give some perspective on how far the technology has advanced. The foundation for the current line of products is an endoscope manufactured in the 1950s. The lens, film, and flash of the camera fit into the space of just a few centimeters. Development started toward the end of the 1940s, when doctors from the University of Tokyo Hospital proposed the idea. Just finding a suitable type of film was a major undertaking. There was no viewfinder and no way of knowing what the images looked like until they were developed. The doctors used to perform the operation in a pitch-black room, using the light from the flash that penetrated the patient’s skin to judge which area they were photographing.

The beginnings of Olympus’ efforts in the endoscope market give some perspective on how far the technology has advanced. The foundation for the current line of products is an endoscope manufactured in the 1950s. The lens, film, and flash of the camera fit into the space of just a few centimeters. Development started toward the end of the 1940s, when doctors from the University of Tokyo Hospital proposed the idea. Just finding a suitable type of film was a major undertaking. There was no viewfinder and no way of knowing what the images looked like until they were developed. The doctors used to perform the operation in a pitch-black room, using the light from the flash that penetrated the patient’s skin to judge which area they were photographing.

(Originally written in Japanese by Kimura Ryōji, freelance writer.)

manufacturing Olympus technology endoscope medicine surgery camera video scope