Leprosy: The Fight to End Legal Discrimination

Society- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

At a meeting held at the Law Society Building in London on January 24, 2013, the International Bar Association endorsed the eighth Global Appeal to end stigma and discrimination against people affected by leprosy. The Global Appeal is led by the Nippon Foundation and its chairman, Sasakawa Yōhei, who is the World Health Organization Goodwill Ambassador for Leprosy Elimination and the Japanese government’s Goodwill Ambassador for the Human Rights of People Affected by Leprosy.

Even countries that pride themselves on their respect for civil rights and equal treatment still maintain laws and regulations that are manifestly unfair in their treatment of individuals affected by leprosy, a condition that today is entirely curable.

With members in 41 countries, the IBA is well placed to mobilize pressure for an overhaul of legal constraints that affect people affected by leprosy and their families. The aim of the appeal is to widen social and economic opportunities for people affected by leprosy and make it easier for them to travel freely.

India has a particularly wide range of discriminatory laws on its books, some of them dating back to the mid-nineteenth century, when medical treatments for leprosy were rudimentary and governments were obsessed with preventing the disease from spreading. But India is certainly not alone.

The launch of the Global Appeal at the Law Society Building in London.

The launch of the Global Appeal at the Law Society Building in London.

In the United States, rules still require all incoming immigrants and refugees to be screened for Hansen’s disease, another term for leprosy. Taiwan imposes a leprosy check on all would-be residents. And it was only in June 2012 that the UK Border Agency confirmed that leprosy was not valid grounds for refusing a visa.

Sasakawa Yōhei speaks at the event to launch the Global Appeal in London.

Sasakawa Yōhei speaks at the event to launch the Global Appeal in London.

The widespread persistence of discriminatory laws like these is the reason why the legal profession was selected as this year’s partner for the Global Appeal, the eighth such annual campaign. Previous partners have included human rights groups, religious and faith leaders, business chiefs, and university chancellors.

“Even today, when leprosy is completely curable, people with the disease continue to face discrimination. In some parts of the world it is still difficult for people with leprosy to remain married or travel freely,” says Sasakawa Yōhei, chairman of the Nippon Foundation, one of the major supporters of the appeal.

“Helping to perpetuate this discrimination are various existing laws and regulations. It may be that these laws were not deliberately kept up, but have remained on the statute books, largely forgotten,” he said at the launch in London. “These discredited laws serve to fan the flames of prejudice and discrimination.”

Personal Commitment

As a World Health Organization goodwill ambassador for leprosy, Sasakawa has a deep personal commitment to the struggle against the disease and the discrimination that sufferers face.

“One of the tasks of my life is to drive leprosy from the world,” he told Nippon.com. “Leprosy is a very ancient disease. It has always been a disease by which human beings have discriminated against other human beings. I don’t know of any other disease that causes even sufferers’ families to abandon the patients as if they didn’t exist.”

Sasakawa points out that the campaign to combat HIV/AIDS—in which he has also been engaged—has benefitted from the support of celebrities such as Elizabeth Taylor. Leprosy has not commanded the same high-profile attention. Those affected continue to face social isolation and discrimination. Even after they have been cured, they are often excluded from society.

Many misunderstandings persist. Sasakawa remembers an African president who admitted that whenever his car passed the local leprosy hospital, he would insist that the car windows be closed and the vehicle accelerate past the building as quickly as possible. Another leader told Sasakawa how he used to warn supporters that they would catch leprosy if they did wrong.

Prejudices and misunderstandings like this create a climate in which legal discrimination remains commonplace. As recently as 2008, China planned to ban those affected by leprosy from entering the country to attend the Beijing Olympics. The bar was lifted only after Sasakawa wrote to President Hu Jintao in person.

Such personal initiatives may occasionally resolve one-off problems. But they are no substitute for systematic and sustained action to secure the removal of discriminatory laws and regulations.

“I have been trying to solve the problem in a systematic way,” Sasakawa says. “Ten years ago, in 2003, I appealed to the United Nations Commissioner for Human Rights. And in 2010 the UN General Assembly adopted a resolution on the elimination of discrimination.”

A rolling program of symposiums around the world will bring experts together and gradually spread the message. Meetings have already taken place in Brazil and India, with Ethiopia, and locations in the Middle East and Europe to follow.

There are still 250,000 new cases of leprosy each year, of which 120,000 are in India, explains Tanami Tatsuya, a Nippon Foundation executive director.

Leprosy is now totally curable, he explains. And because the symptoms are visible, regular check-ups can ensure that new cases are caught at an early stage. In Uttar Pradesh state in India, for example, schoolchildren are given a simple questionnaire through which they can report symptoms. But progress is not without its risks, Tanami points out: “Leprosy is no longer a massive public health problem, so governments in some developing countries are becoming a little complacent, cutting budgets and training for local health workers.”

Struggles Lie Ahead, Even After Cure

Helena Kennedy, co-chair of the IBA’s Human Rights Institute.

Helena Kennedy, co-chair of the IBA’s Human Rights Institute.

Moreover, even after they have been successfully treated, those who have had leprosy still face widespread social and legal obstacles to fulfillment in life. “I was bowled over to find the extent of discrimination and suffering,” says Baroness Helena Kennedy QC, cochair of the IBA’s Human Rights Institute.

She points out that discrimination can even make treatment less effective. Even if someone has detected the early symptoms of the disease, a person may decide not to come forward for prompt treatment if they fear they will be discriminated against as a result.

India is a striking example of the legal constraints that are still in effect. Leprosy continues to be cited as legitimate grounds for divorce, and in several states people affected by leprosy are denied their right to stand for election to local councils. People can be forcibly removed from residential areas and taken to reserved premises, even if they have been cured. Kennedy points out that India’s 1999 Motor Vehicles Act even deprives people of the right to hold a driver’s license if they have leprosy.

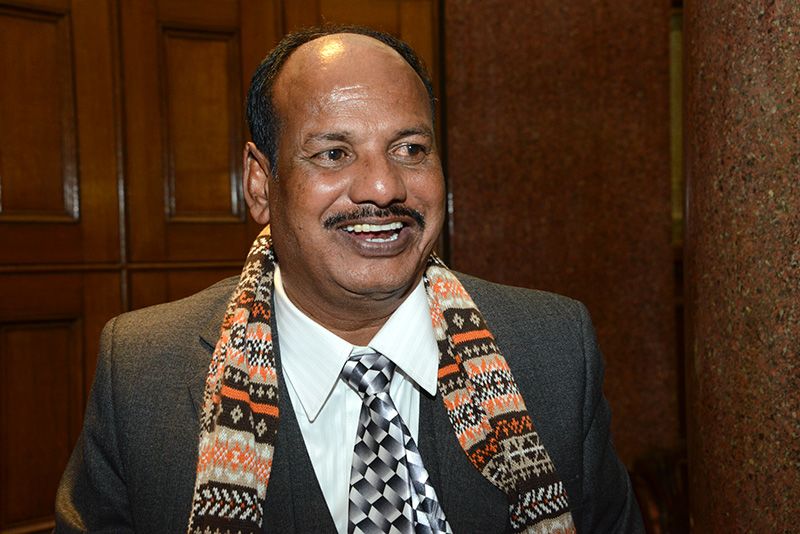

Vagavathali Narsappa of the Society of Leprosy Affected Persons.

Vagavathali Narsappa of the Society of Leprosy Affected Persons.

Indian leprosy campaigners report that there has been some progress in recent years. But the problems remain huge. Vagavathali Narsappa, who set up the Society of Leprosy Affected Persons in Andhra Pradesh in 2006 to represent the state’s 101 leprosy colonies. He recalls how he was excluded from his own village as a child, even after he had been cured.

Guntreddy Venugopal—like Narsappa, a vice-chair of the National Forum of People Affected by Leprosy in India—told Nippon.com that schools often deny admission to children suspected of having had leprosy. Simply attending hospital for treatment for leprosy can be enough to transform someone into a social outcast. They will often find it difficult to secure work—despite the efforts of some major companies such as the Tata Group, who do employ people affected by the disease. A woman will struggle to find a husband. “The challenge is to change the mindset. We need to increase pressure for change,” Venugopal says.

Narsappa and Venugopal point out that affected people sometimes go to live in a leprosy colony because that is the only place where they can be accepted and given a chance to build relationships and a normal family life.

Some progress has been made in using legal action to fight for the rights of those affected by the disease. Andhra Pradesh, for example, has a good court system and a network of human rights lawyers. A case has been filed to secure reliable access to medical treatment for people affected by leprosy, many of whom are particularly vulnerable to injury because they have lost some of the sensation in their limbs.

Narsappa and Venugopal hope that the new partnership with the IBA and the support of the Nippon Foundation will help to mobilize resources for more action to tackle the lingering vestiges of legal discrimination against people affected by leprosy.

Nippon Foundation London leprosy International Bar Global Appeal discrimination Hansen’s Disease