The Japanese Teacher of Islam

Society Culture Lifestyle- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

A Negative Image

Muslims account for around a quarter of the world’s population today. In Japan, however, they are thought to make up less than one percent of the total population. Shimoyama Shigeru, who works at the country’s largest mosque in Tokyo, is a Japanese convert to Islam. We spoke to Shimoyama to find out more about the Muslim faith in Japan and his own life as a believer.

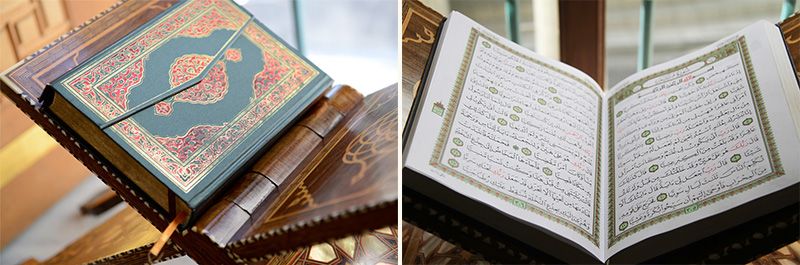

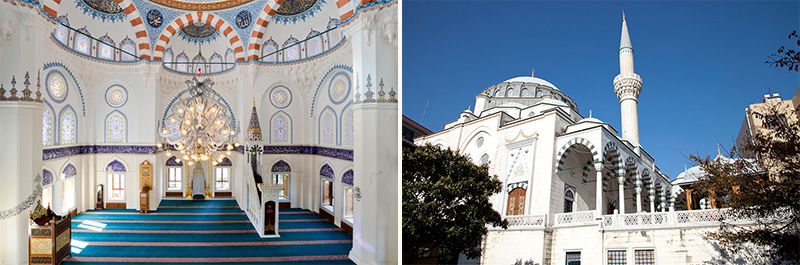

Tokyo Camii, one of the most beautiful mosques in East Asia. (Photo on the right courtesy of Tokyo Camii.)

Tokyo Camii, one of the most beautiful mosques in East Asia. (Photo on the right courtesy of Tokyo Camii.)

INTERVIEWER Why do you think Islam has remained so remote from Japanese mainstream culture in the past?

SHIMOYAMA SHIGERU Since the Meiji Restoration in 1868, modern Japan has modeled itself on countries like Germany, Britain, and France. These countries provided the models for Japan’s modern system of legislature and commercial law. A side-effect of this has been that non-European values, including those of Islamic cultures, have tended to be overlooked.

Also, I think Japan inherited a somewhat biased European view of Islam, and this has exacerbated this tendency. For instance, a lot of people in Japan became familiar with the expression “Either the Koran or the sword,” and this has gotten in the way of a proper understanding of Islam. Particularly after 9/11, the impact of media coverage has made Islam seem an intimidating and “scary” religion to a lot of people.

Equality Before God

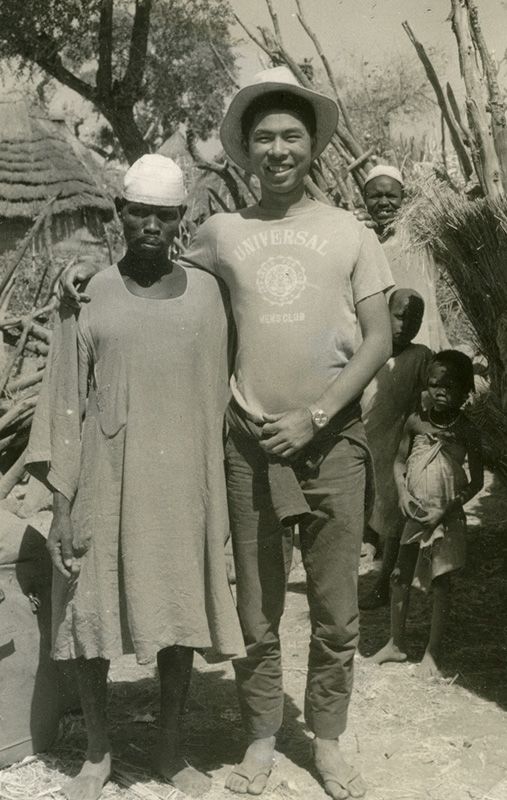

Shimoyama Shigeru during his year-long trip to Africa. (Photo courtesy of Shimoyama Shigeru.)

Shimoyama Shigeru during his year-long trip to Africa. (Photo courtesy of Shimoyama Shigeru.)

INTERVIEWER Apparently about five Japanese people enter the Islamic faith every month. But during our visits, we’ve seen very few Japanese worshipers. What made you decide to become a Muslim when the religion is so unfamiliar to most people in Japan?

SHIMOYAMA When I was a university student, I took a trip on a rubber raft down the Nile, staying in villages along the way. Everywhere I stopped, people were sure to provide me with a place to spend the night, even though I barely spoke a word of their language. The Africans I met were Muslims, and their hospitality made a deep impression on me. I was surprised to learn later that their kindness came from Islamic teachings.

That experience was the starting point for the person I am today. To be honest, I never had much belief in God until I became a Muslim. But once I joined the Muslim community and started to worship alongside other Muslims of all races, side by side as brothers, I realized what a wonderful thing this belief is.

A view of the “bird nests” built onto the exterior walls of Tokyo Camii, symbolizing that all living creatures are part of God’s creation.

A view of the “bird nests” built onto the exterior walls of Tokyo Camii, symbolizing that all living creatures are part of God’s creation.

The reason we worship in lines alongside each other goes to the heart of the spirit of Islam, which says that all believers are equal before God. There is also the belief in justice, or birru; this is the idea that you should always think about the needs of others first. This belief frees you from an egotistical way of thinking. These Islamic ideas have become deeply engraved in my heart.

A hexagonal pattern at Tokyo Camii that conveys the concept of “infinity” and “perfection.”

A hexagonal pattern at Tokyo Camii that conveys the concept of “infinity” and “perfection.”

Islam places a strong emphasis on correct behavior and the virtues of charity. During the Ottoman Empire, from the fourteenth to the sixteenth century, a system based on the Islamic idea of giving wealth back to society was set up to direct surplus resources toward social needs rather than economic activities. This was handled by a charitable organization called waqf—a precursor to today’s NGOs and NPOs. The funds raised were used to build hospitals, schools (called madrasas), and other facilities for the weaker members of society. The areas around mosques attracted madrasas, hospitals, bazaars, and simple eating houses that provided free meals to poor people. Charitable donations from sultans, government officials, and regular citizens were used to bridge the gap between rich and poor.

Making Guests Feel at Home

INTERVIEWER You have said that for tourists from Southeast Asia—particularly Indonesia and Malaysia—Tokyo Camii has become a major sightseeing spot, ranking alongside Kyoto, Mount Fuji, and Tokyo Disneyland.

SHIMOYAMA That’s right. I think we’ll see more and more tourists from Southeast Asia visiting Japan in the future. The only thing holding the numbers back at the moment is a lack of restaurants serving halal food in Japan and hotels with prayer facilities. Japan prides itself on its hospitality to travelers, but I think there’s some room for improvement when it comes to considering the needs of Muslims.

SHIMOYAMA That’s right. I think we’ll see more and more tourists from Southeast Asia visiting Japan in the future. The only thing holding the numbers back at the moment is a lack of restaurants serving halal food in Japan and hotels with prayer facilities. Japan prides itself on its hospitality to travelers, but I think there’s some room for improvement when it comes to considering the needs of Muslims.

“Human Contact” Is Key

INTERVIEWER As Japan’s ties with Muslim countries grow closer, what can Japanese people do to understand Islam better?

SHIMOYAMAEverything begins with personal interaction—human contact. It’s through human contact that we make new discoveries.

This was certainly true in my own case. It was my personal relationship with an Iraqi student at the University of Tokyo that gave me the decisive push I needed when I was thinking of immersing myself in Islam. He certainly never told me to become a Muslim. But I think I was drawn to his personal charm, and I realized that his kindness and brotherly love was intricately bound up with his faith as a Muslim.

Friday prayers at Tokyo Camii attract a large congregation of worshipers. (Photo courtesy of Tokyo Camii.)

Friday prayers at Tokyo Camii attract a large congregation of worshipers. (Photo courtesy of Tokyo Camii.)

Islam is essentially a way of life—it is present in every aspect of the daily life of a devout Muslim. I hope that people will become interested in Islam through seeing its influence in aspects of everyday life, and that personal contact with Muslims will help them to understand Islam better. Of course, some people simply visit the mosque to appreciate it as a work of art. But the realization of how beautiful a mosque might also be the starting point of someone’s journey to Islam.

What’s a good way to initiate that “human contact” I was talking about? Well, when you meet a Muslim, you should reach your hand out and say: Assalamu Alaikum, “peace be upon you.” This simple greeting will make them feel at ease. I just said these words a few minutes ago to a mother and child visiting from Kashmir, and I could tell right away from the friendly smile they gave me that they were happy to be welcomed by this familiar greeting so far from home.

INTERVIEWER Lastly, do you have any message for readers in Japan and around the world?

SHIMOYAMA I was lucky to experience aspects of Africa that most Japanese people don’t have a chance to encounter, so I hope I can make a positive contribution. I want to do whatever I can to clear up some of the misunderstandings Japanese people have about Islam and convey a correct understanding of the religion to as many people as possible.

(Translated from an interview in Japanese, with assistance from Tokyo Camii and Turkish Culture Center. Photographs by Kodera Kei.)

Tokyo Arabic Islam Muslim religion mosque Turkey Arabic calligraphy Camii