The Bells of Nagasaki Ring On

Society Culture- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Nyokodō: “Love Your Neighbor as You Love Yourself”

“Comforting, cheering, the bells of Nagasaki ring!” The song “The Bells of Nagasaki,” sung by Fujiyama Ichirō, was a tremendous hit in 1949, not long after the end of World War II. This year, 2015, marks the seventieth anniversary of the atomic bombing of Nagasaki on August 9, 1945. That event cannot be discussed without mention of the radiologist Nagai Takashi, who wrote many books about the bombing, including, most famously, Nagasaki no kane (The Bells of Nagasaki).

The score and lyrics of the song “The Bells of Nagasaki” are carved on a wall near the Nyokodō.

The score and lyrics of the song “The Bells of Nagasaki” are carved on a wall near the Nyokodō.

The achievements and publications of Nagai, who set about treating and helping many sufferers even though he himself had been exposed to radiation and seriously injured, are a superb firsthand record of the atomic bombing. At the same time, as a Christian, his life was full of a love of humanity and a desire for peace.

Midway up a hill near the Statue of Peace, a symbol of Nagasaki, is a wooden hut consisting of just one tiny room. It was here that Nagai, who had collapsed from leukemia and was lying sick in bed, managed to pen 17 books over a period of four and a half years. He christened the dwelling Nyokodō in reference to the Christian maxim “Love your neighbor as you love yourself.” The naming was an expression of his intention never to forget the people of the Urakami district, which was situated near the hypocenter and therefore saw many deaths and injuries, and to live his own life amid that wellspring of affection.

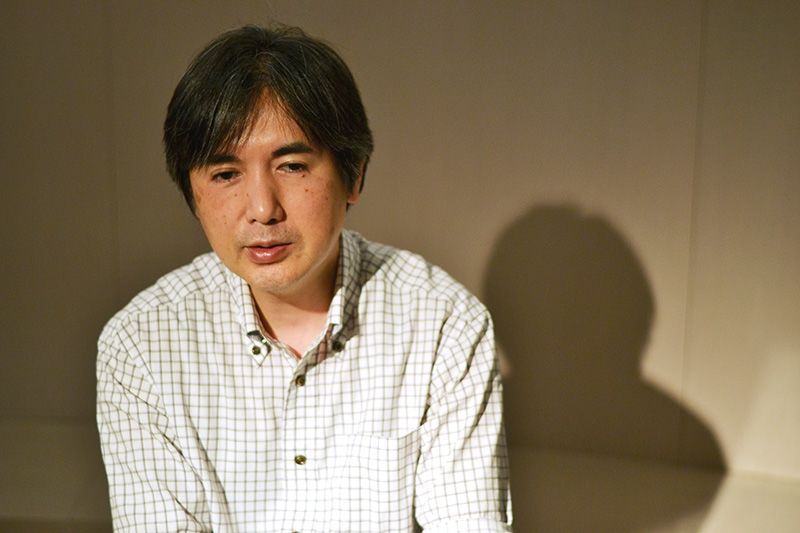

I visited Nagai’s Nyokodō, which many Japanese are beginning to forget, and spoke with Nagai’s grandson Nagai Tokusaburō, who is director of the adjacent Nagasaki City Nagai Takashi Memorial Museum.

“Three More Years to Live”

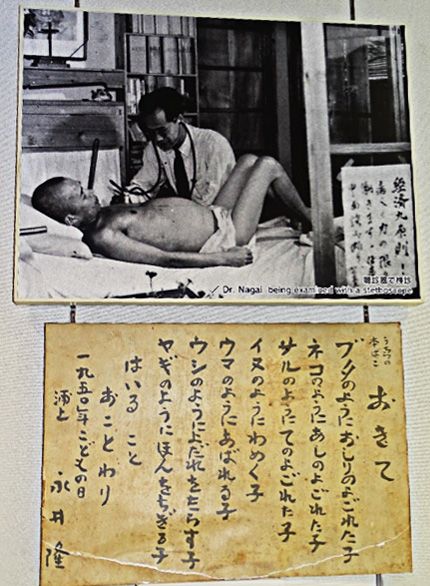

An exhibit at the Nagai Takashi Memorial Museum shows Nagai receiving treatment at the Nyokodō.

An exhibit at the Nagai Takashi Memorial Museum shows Nagai receiving treatment at the Nyokodō.

Nagai Takashi was born in Matsue, Shimane Prefecture, in 1908. After graduating from Nagasaki Medical College (now the School of Medicine of Nagasaki University), he was involved in treatment and research in the field of radiology and also in the treatment of tuberculosis, which was the most serious disease at that time. Nagai himself contracted chronic myeloid leukemia, and two months before the atomic bombing, he was told that he had only three more years to live. He was 38 at the time.

Moreover, on the day of the bombing Nagai was working in the college hospital, where he suffered radiation exposure and severe injuries, including a severed right carotid artery, in the explosion. His beloved wife Midori was burned to death at their home. In The Bells of Nagasaki, Nagai described the immediate aftermath of the bombing as follows: “‘Hell! This is hell!’ No one even groaned. It really was the world of the dead.”

Immediately after the bombing, despite his own injuries, Nagai became involved in first-aid and relief activities. After recovering and burying the remains of his wife, as the head of the Eleventh Medical Corps he built a first-aid station in Koyamamachi in Nagasaki, where he treated radiation sufferers. During this period Nagai himself became critically ill, but somehow he miraculously recovered.

In 1946, Nagai was promoted to the position of professor at the Nagasaki Medical College. In July of that year, though, he collapsed at Nagasaki railway station and was confined to bed. Lying face-down on a narrow mattress at home, he began to devote all his remaining energy to writing. Two years later he moved to the tiny Nyokodō, which the people of Urakami had built for him using wood that had escaped the atomic flames.

GHQ Censorship Delays Publication

Nagai finished writing The Bells of Nagasaki in August 1946, but publication was no easy matter. The book ran afoul of the strict censorship of the occupying General Headquarters of the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers. The Bells of Nagasaki, a record of the atomic bombing from a medical perspective, was the first manuscript concerning the bombing to be written, either in Japan or overseas. More than two years passed before permission for publication was received, and even then the GHQ imposed a condition.

The condition was that The Bells of Nagasaki must be jointly published with The Sack of Manila, which described a massacre by the Japanese military in Manila in February 1945. The Sack of Manila had been compiled by the GHQ’s Intelligence Division on the basis of oral testimonies of the massacre by priests, military personnel, civilians, and others.

The Bells of Nagasaki was eventually published in January 1949, and despite appearing at a time when paper was in short supply, it became an unprecedented bestseller. In July of the same year the song, written by Satō Hachirō and composed by Koseki Yūji, was released and became a big hit. In the following year the singer Fujiyama Ichirō visited Nagai at Nyokodō, taking an accordion along with him. Later Fujiyama performed the song in the final slot in the first NHK Kōhaku Uta Gassen (Red and White Year-end Song Festival), broadcast on January 3, 1951.

In addition, in 1950 Shōchiku released a movie of The Bells of Nagasaki directed by Ōba Hideo and starring Wakahara Masao as Nagai, together with Tsukioka Yumeji and Tsushima Keiko. The first film to take up the atomic bombing was subject to GHQ censorship and unable to portray conditions as they were. Rather than tackling the horror of the atomic bombing, the movie emphasized the desire for reconstruction.

A film about Nagai’s life titled All That Remains, shot by a British production company, is due to hit cinemas soon.

Visit by Helen Keller

Nagai Tokusaburō says that the Nagasaki City Nagai Takashi Memorial Museum is visited by about 150,000 people every year. Originally the museum was a small reading room called Uchira no Honbako (Our Bookcase), which Takashi built with his own savings for children who had lost their parents in the war. Later, with donations from Japanese residing in Brazil and financial assistance from the Nagasaki government, this reading room became a library, and then in 1969 it changed its name and became a museum displaying items left by Nagai and photographs. It was completely rebuilt in 2000. The exhibit space is not very large, but according to Tokusaburō, “Some visitors spend 30 or 40 minutes here and don’t utter a word before they leave.”

Many people visited Nagai at his Nyokodō home, but the visit by Helen Keller on October 8, 1948, was quite out of the blue. Although it was only a brief 15-minute encounter, Nagai was moved to tears. In Itoshi ko yo (My Precious Child), he wrote, “We held hands! In an instant, I felt the warmth of her love flow through my extremities like electricity through a closed circuit.”

Nagai also had an audience with Emperor Hirohito, who visited the disaster area in Nagasaki on May 27, 1949. Three days later he kissed the mummified right arm of Saint Francis Xavier (1506–52), which had been brought to the Urakami community hall, and received a visit from Cardinal Norman Thomas Gilroy, an emissary of the pope. At the end of that year Nagai became the first honorary citizen of Nagasaki.

A Longing for Permanent Peace

Urakami Cathedral was rebuilt in 1959.

Urakami Cathedral was rebuilt in 1959.

Until his university days, Nagai had been a follower of Izumo Shrine and not a believer in Christianity. It was after entering Nagasaki Medical College that, hearing the Angelus bells of Urakami Cathedral ringing every day and reading Pensées (Thoughts) by the seventeenth-century philosopher Blaise Pascal, he became drawn to Christianity.

Nagai was baptized in 1934 after returning to Japan from the battlefields of Manchuria. In August of that year he married Moriyama Midori. She was from a family of devout Christian believers stretching back through seven generations of “hidden Christians” who survived the anti-Christian edicts of the seventeenth century by concealing their faith and going underground. Nagai took the baptismal name of Paulo after Paulo Miki (1562–97), one of the Twenty-Six Martyrs of Japan who were crucified in Nagasaki in 1597 by order of Toyotomi Hideyoshi.

Tokusaburō says, “People called Nagai Takashi a saint, but he did not wish to be addressed in that way.” He adds, “I would like the young generation to understand my grandfather’s thoughts about and his longing for permanent peace through neighborly love and to reflect those feelings in their lives.”

Nagai Takashi welcomed the enforcement of the Constitution of Japan on May 3, 1947. In Heiwa no tō (Tower of Peace) he wrote, “I have never felt as strongly as I do now that people must not start wars. It is purely the result of the two atomic bombings. The Constitution goes as far as to renounce war, so we really must exorcise the concept of war from people’s minds.”

“Time to Let Him Rest Peacefully”

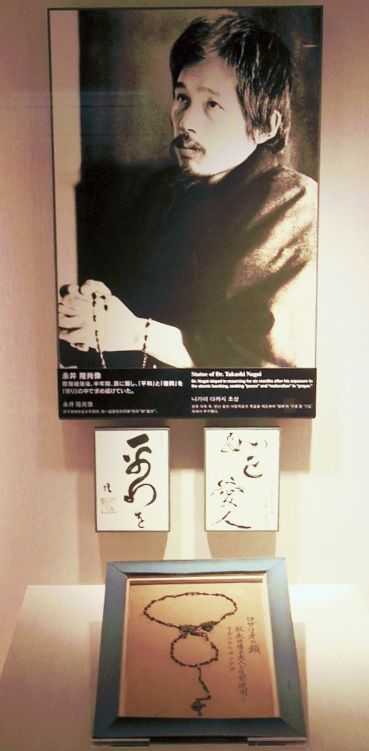

A photo of Nagai Takashi exhibited at the Nagasaki Atomic Bomb Museum.

A photo of Nagai Takashi exhibited at the Nagasaki Atomic Bomb Museum.

The title The Bells of Nagasaki refers to the two Angelus bells at Urakami Cathedral that Nagai heard in his student days. One of the two bells survived the atomic bombing intact. On December 24, 1945, it was retrieved from the debris by some Christian believers, hung from a log, and rung to announce the Christmas Eve mass. Nagai heard the ringing of the bell for the repose of the dead and decided on the title of his book.

In our talk, Tokusaburō told me: “Recently I am often asked what Takashi, had he been alive, would have said about the nuclear plant accident after the Great East Japan Earthquake. But I think he would have replied that the question was a little off the mark. He would probably have said that we should have acted before the accident in consideration of the safety and danger of nuclear power. I don’t think he would have made any clear-cut comment.”

Nagai passed away at the Nagasaki Medical College Hospital on May 1, 1951. He was 43 years of age. An autopsy revealed that his spleen was swollen to 35 times the normal size and his liver to 5 times. On May 14, a public funeral was held at Urakami Catholic Church, attended by 20,000 citizens. According to the book by Nagai’s son, Seiichi, the Nagasaki-born chanson singer and actor Miwa Akihiro was present.

At the end of our conversation, Tokusaburō spoke reflectively: “Someday the war and the atomic bombing might be forgotten. . . . I think the time has come to let him [Nagai Takashi] rest peacefully.” As long as the bells of Nagasaki continue ringing for the repose of the dead, however, Nagai Takashi’s existence will remain unchanged.

(Originally written in Japanese and published on July 22, 2015. Banner photo: The present Nyokodō, Nagai’s tiny wooden home, is situated on the right-hand side of a hill leading up from the Statue of Peace toward the municipal Yamazato Elementary School. Courtesy Nagasaki City Nagai Takashi Memorial Museum.)

Radiation World War II Nagasaki atomic bombing Nagai Takashi