Remarkable Recovery: The Modern History of Japan’s Environment

The Recovery of the Short-Tailed Albatross: A Preservation Success Story

Society- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Down Feathers: A Lucrative Commodity

Down feathers, once a luxury item reserve for the wealthy, came to be widely used in the West near the end of the eighteenth century when the Industrial Revolution made it possible to mass-produce down-filled bedding. Harvested from the breasts of water birds, down is prized for its light weight, absorbency, and warmth. For a long time, the down of the short-tailed albatross was especially popular and could be sold for a high price.

At least 1.1 to 1.3 kilograms of down is needed for a single futon, but only 10 to 20 grams can be taken from a single albatross. Nearly 100 birds need to be killed to get enough down for one futon. Today, down duvets are usually made with artificial fibers or the feathers of geese and ducks, birds available in much greater numbers.

Driven to the Brink of Extinction

Tamaoki Han’emon, a Meiji-era entrepreneur, started exporting albatross down feathers to the United States and Europe around 1885, raking in massive profits. His success was widely reported in newspapers and trade journals, sparking a rush of copycat opportunists. The albatross colonies were decimated to the point where all that was left was one colony on Mukojima on the northern edge of the Ogasawara Islands.

By the end of the 1880s, the tide of opportunists seeking albatross down feathers had reached the Senkaku Islands, and when Taiwan became a Japanese colony following the Sino-Japanese War of 1894–95, they surged further to the uninhabited islands north of Taiwan and soon thereafter to the island of Angaur and the Caroline Islands in Micronesia. In 1900, Tamaoki, having completely depleted the albatross colony on Torishima, also made his way south to Minami Daitōjima.

Even the American-controlled Midway Islands and the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands fell prey to the down harvesters, who entered the islands illegally, leaving the coastlines littered with piles of plucked albatross carcasses.

When US Navy research vessels discovered the carnage, the Japanese were denounced as a cruel people in the United States, which was already being swept by anti-Japanese sentiment. In 1903, the US Naval Station in Hawaii issued a demand to the Japanese consulate to stop the harvesting of seabirds in the waters around the Hawaiian Islands, but the poaching continued.

Learning of the situation, US President Theodore Roosevelt declared the northwestern Hawaiian Islands and their surrounding waters to be a bird sanctuary. Later the sanctuary was expanded into the Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument, today the most expansive marine wildlife reserve in the world and a World Heritage site. It currently hosts Earth’s largest population of albatrosses.

A Bird Population on the Edge

When Yamashina Yoshimaro, founder and director of the Yamashina Institute for Ornithology, visited Torishima in 1930 he reported a colony of around 2,000 albatrosses. Just three years later, when he sent Yamada Nobuo to investigate, there were only a few dozen birds left. In 1933, Yamashina successfully lobbied to have Torishima declared a bird sanctuary to prevent any further decimation of the dwindling colony.

Little is known of how the albatross colonies fared just before, during, and after World War II. After the war, the first person to land on Torishima for the purpose of studying the island albatrosses was Oliver L. Austin, an ornithologist with the Natural Resources Division of the Occupation authority in Japan, the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers.

Austin worked in Japan from 1946 to 1949, introducing improvements in Japan’s laws for wildlife sanctuaries and wildlife protection policies. He left numerous animal specimens, as well as photographs of Tokyo in the immediate postwar years that can be viewed on the Internet.

In March–April 1949, Austin went on an expedition to survey the wildlife on the southern Izu Islands and the northern Ogasawara Islands. The waters were too rough to land at Torishima, but he still made repeated observations from his ship, later reporting his now famous assertion that the island albatrosses were extinct.

The Discovery of Survivors

In 1947, the Japan Meteorological Agency built an observatory on the island primarily for tracking typhoons. Agency staff were stationed at the observatory for 18 years until 1965, when they were all evacuated due to a series of earthquakes caused by volcanic activity. Staff member Yamamoto Shōji was the first to “rediscover” the island’s short-tailed albatrosses on one of his regular inspection tours when he came across a small group of around a dozen birds nesting along the steep cliffs of Torishima’s southeast coast.

Following this discovery, the observatory staff set about to protect the small colony and were soon joined in their efforts by researchers who took advantage of the occasional ferries carrying food and supplies to the observatory to make their way to the island. At this point, the largest number of birds counted was 42. In 1958, the Torishima short-tailed albatross was designated a nationally protected species, a ranking elevated in 1962 to special nationally protected species.

The ferries to Torishima stopped running after the observatory was closed, effectively shutting down any information on how the island’s birds were faring. It was not until April 1973 that British ornithologist Lance Tickell and Yoshii Masashi of the Yamashina Institute for Ornithology were taken to the island by a British naval vessel. They were able to confirm the presence of only 25 adult birds and 24 chicks.

Hasegawa Hiroshi, currently a Tōhō University professor emeritus, was a graduate student at Kyoto University when he attended one of Tickell’s seminars. He was profoundly affected by Tickell’s research and was soon totally immersed in his own conservation efforts on the short-tailed albatross. He recalls now how amazed he was that the British navy would assist in the survey of birds on an isolated island. Hasegawa has devoted his life to the revival of the short-tailed albatross, with his passion driving considerable personal efforts toward this objective. He has made numerous trips to Torishima, accumulating a total of 2,473 days on the small island.

Seabird researcher Hasegawa Hiroshi has dedicated his career to reviving the albatross population in Japan.

Seabird researcher Hasegawa Hiroshi has dedicated his career to reviving the albatross population in Japan.

A Steady Revival

Hasegawa was troubled to find that less than half of the eggs laid by the albatrosses would hatch. Their nests were perched on precarious slopes of loose volcanic soil with little vegetation, and he surmised that more often than not the eggs and newly hatched chicks were the victims of frequent landslides.

Urged by Hasegawa, the Japanese Environment Agency (now the Ministry of the Environment) and the Tokyo metropolitan government began in 1981 to transplant Hachijō susuki grass (Miscanthus condensatus Hack.) for sediment control. But there was another major concern: Torishima was an active volcano and might erupt at any time.

Staff of the former Environment Agency prepare an albatross breeding ground.

Staff of the former Environment Agency prepare an albatross breeding ground.

The albatross breeding grounds were concentrated on a slippery slope on the southeast side of Torishima. It was decided in 1991 to prepare a new breeding ground on the opposite western side of the island, where there was grass and the conditions seemed better.

As it happened, in the spring of that same year Uchiyama Haruo, a master craftsman of bird carvings, brought one of his lifelike albatross decoys to Institute Director Yamashina. Could the decoys, he asked, be used somehow to help revive the endangered species?

Albatross decoys carved by bird-carving artist Uchiyama Haruo

Albatross decoys carved by bird-carving artist Uchiyama Haruo

Thinking that the decoys might attract the albatrosses to the safer breeding grounds, institute workers sought funding to make almost 100 decoys, which they installed on the western slope. They reinforced the illusion of a colony by broadcasting recordings of albatross calls and waited to see what would happen.

In 1993, with the official designation of the short-tailed albatross as a national endangered species, the Environment Agency (now the Ministry of the Environment) provided support for the efforts to protect the species. Additional funding and researchers also came to the Yamashina Institute from the US government, which had also designated the albatrosses of the North Pacific as an endangered species.

The decoy strategy proved to be highly successful. Eggs were confirmed in the new breeding grounds for the first time in the autumn of 1995, and by June 2005, a total of 11 chicks had grown and left their nests. The most recent study has identified 274 pairs in a colony that has expanded to cover a full third of the island.

A short-tailed albatross parent and chick.

A short-tailed albatross parent and chick.

Following the success of the second breeding ground, a new project was launched in 2006 to translocate some of the birds to another island. Newly hatched chicks were taken to Mukojima and artificially raised to be released when they attained adulthood. A bird named Ichirō was the first of these artificially raised chicks to return to Mukojima after having been released.

The dramatic recovery of Japan’s short-tailed albatross colonies has attracted worldwide attention, as there is little precedent for such a successful revival of a large-bird population once on the brink of extinction. New Zealand has 14 albatross species on its islands, several of which are dangerously near extinction. Efforts modeled on those of Japan are now underway to save two of those species.

A Goal of 5,000 Birds

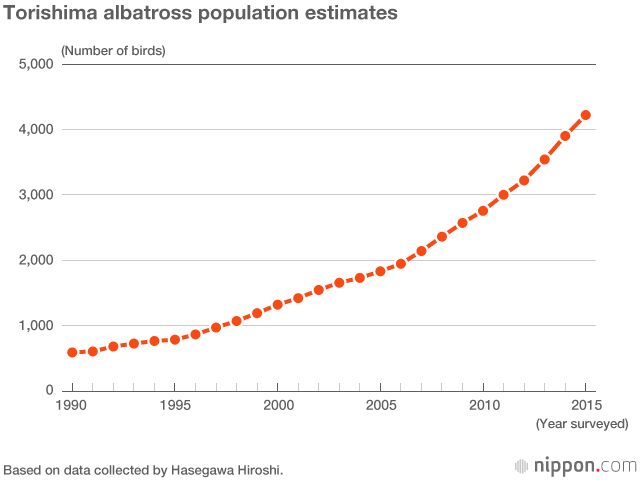

The number of chicks on Torishima growing to adulthood and leaving their nests is increasing every year. Whereas the estimated population of short-tailed albatrosses was around 250 in 1980, this number grew to 600 in 1993, and by 1999 had exceeded 1,000. In 2009, there were 2,570 birds; a survey carried out in March 2016 counted a total of 4,220.

The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species published by the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources ranks the danger of extinction in seven categories, from Extinct (EX) to Least Concern (LC). Once ranked as Endangered (EN), the short-tailed albatross has been downgraded one category to Vulnerable (VU).

Hasegawa has repeatedly asserted that his goal is to get the short-tailed albatross population up to 5,000 birds. At the current pace, this should be achieved in 2019, and the key is the translocation project. Hasegawa has one more objective, and that is to get the derogatory Japanese name for the short-tailed albatross—ahōdori, meaning “foolish bird”—changed to okinotayū (“grand master of the seas”), a much more elegant name of respect that has long been used in the Nagato area of Yamaguchi Prefecture.

Photos by Hasegawa Hiroshi

(Banner photo: The decoy installation on Torishima. © Hasegawa Hiroshi.)