Remarkable Recovery: The Modern History of Japan’s Environment

Rebellion of the Wild

Society- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

A Source of Deep Resentment

Back in the days when I was teaching at a university in Hokkaidō, some colleagues and I were out drinking when one of my friends mentioned that it would be nice to have some good soba, or buckwheat noodles, to go with his drink. The conversation switched to noodles, and we all agreed with great enthusiasm that we should grow our own buckwheat. Noodles made from grain we had cultivated ourselves would surely be the best. Somebody piped up that he had some land that we could use at his mountain cottage. That decided the matter, and our project took off from there.

Our enthusiasm cooled rather quickly after the effects of the liquor wore off, however. I had to push, pull, and cajole my fellow teachers, so full of talk but little action, to get the project going. We finally got a small plot of a little less than 100 square meters cultivated, planting the seeds as best we could with blistered hands unaccustomed to physical labor. We took pride in the reports that seedlings had sprouted, and later, that the buckwheat had flowered. At last the day came to harvest our crop. We went out and purchased brand-new sickles and gathered with enthusiasm at the mountain field—only to find it had been razed to the ground. Our buckwheat had disappeared.

A local retired farmer who occasionally made the rounds to check on my friend’s cabin greeted us. “Two, three nights ago a bunch of deer came and had themselves a feast,” he said with glee. “Take that, you amateurs,” his expression seemed to say. “What could you know of the trials of farming?” We were bitterly disappointed.

Ravaged Fields

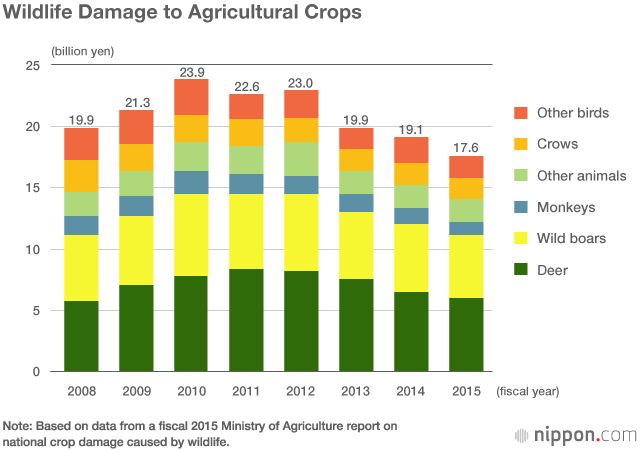

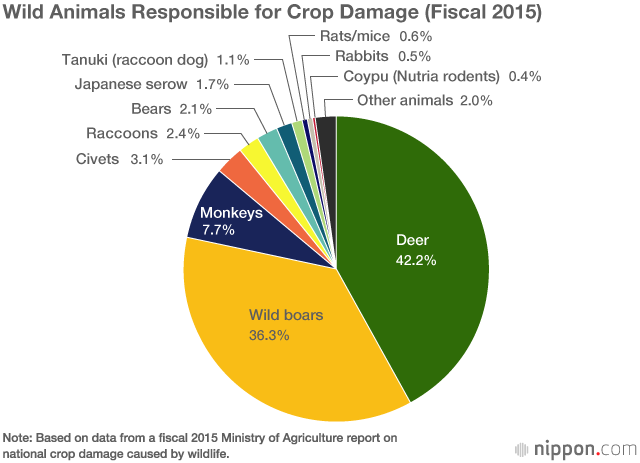

There seems no end to the crop damage caused by wildlife. According to the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry, and Fisheries, crop damage caused by animals and birds reported throughout the country in fiscal 2015 totaled a loss of ¥17.6 billion. While this was roughly 8% less than the preceding fiscal year, the damage remains costly. Some authorities assert that if unreported cases were included, the total could be considerably higher.

Of all the 17 animals and birds studied, deer and wild boar are responsible for the highest rates of damage. Deer accounted for nearly ¥6 billion in damage and wild boar around ¥5 billion. They are followed by crows and monkeys. The cost of damage caused by wild boars has changed little over the past decade, but that caused by deer has gone up by 50% as the havoc they wreck spreads.

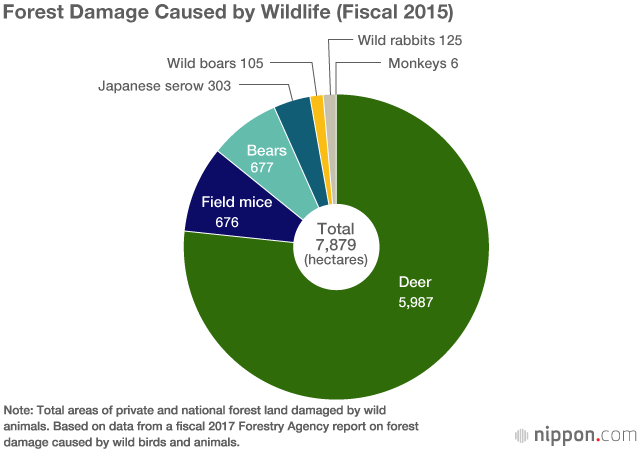

The Forestry Agency’s fiscal 2015 report on forest damage caused by wildlife says that of the nearly 8,000 hectares of damaged forest land throughout Japan, as much as 77% was caused by deer. Economic damage has been most severe in planted forests, where deer have eaten the bark of large trees, but the economic repercussions also extend to cultivated mushrooms and bamboo sprouts.

The Effects on the Ecosystem

Japanese deer, a species of sika deer (Cervus nippon), are to be found throughout the country. They are grouped by location into seven varieties, including Ezo, Honshū, and Yaku deer. The largest are the Ezo deer of Hokkaidō, some of which can weigh as much as 140 kilograms and require 2.5 kilograms of plant feed every day.

Typical Japanese deer in their appearance from spring to summer (left) and autumn to winter. (Illustration by Izuka Tsuyoshi)

Typical Japanese deer in their appearance from spring to summer (left) and autumn to winter. (Illustration by Izuka Tsuyoshi)

More and more regions in Japan are seeing scenic forestry and plant growth ravaged by foraging deer. The list is almost unending, but includes such places as the Shiretoko Peninsula in Hokkaidō, the mountains of Goyō-zan in Iwate Prefecture and Kinka-san in Miyagi Prefecture, the Nikkō mountains in Tochigi Prefecture and the nearby Oze National Park, the Tanzawa mountains in Kanagawa Prefecture, the southern Japan Alps in Nagano Prefecture, the Suzuka, Daikō, and Ōmine mountains in the Kinki region, the mountain Kasugayama in Nara Prefecture, central Hyōgo Prefecture, and Yakushima in Kagoshima Prefecture. According to statistics compiled by the Environment Ministry, 20 out of the 30 national parks on Japan’s main islands, where deer populations are present, have damage caused by the animals.

A few years ago, I took my grandchildren to search for Hemerocallis esculenta, a kind of daylily, in the marshes of the Oze National Park. Normally in that season, the marshes would present themselves as a carpet of orange flowers—but when we went, every single flower had been eaten by deer and the landscape was entirely denuded. More recently, deer appear to have added to their diet the stems and flowers of mizubashō (Lysichiton camtschatcensis, the Asian skunk cabbage), another popular marsh plant. I have visited the Oze marshes numerous times over the past 50 years and never expected to see such a sight.

In forest areas with large deer populations, the deer eat so much of the shrubbery and fallen leaves that they have exposed large swatches of the ground to rainfall, causing serious soil erosion leading to landslides along steep slopes. Dead trees litter the Ōdaigahara plateau in the Yoshino-Kumano National Park as a result of deer damage, and soil erosion can be spotted here and there in what has long been considered one of Japan’s top 100 scenic areas.

Pithecops fulgens tsushimanus, a species of butterfly belonging to the Lycaenidae family that is only found on the island of Tsushima in Nagasaki Prefecture, was just declared an endangered species in 2017 because deer have overeaten a certain species of tick-trefoil (Desmodium podocarpum subsp. Oxyphyllum), that is the primary food for the insect in its caterpillar phase.

Once on the Verge of Extinction

Deer were protected to an extent during the Edo period (1603–1868) by a ban on killing animals for their meat, but this did not mean they escaped the hunt. During this era deer continued to be killed not only for their meat but also for their skin and horns, which were used on military armor and weapons, as well as other apparel and leather goods. Even so, there was no significant diminishing of the deer population.

In the early years of the Meiji era (1868─1912), the government encouraged the hunting of deer so that the hide and meat could be canned and exported for cash income to fund the country’s development. Ezo deer were a particularly favorite type of game, and 570,000 were killed from 1873 to 1878. Record-breaking snowfalls in 1879 nearly drove the Ezo deer to extinction, and from 1890 to 1910, the hunting of deer was prohibited. This pattern of overhunting and prohibition was repeated several times over the following decades.

As the Japanese population increased and development progressed, wild animals were driven deep into the mountains and were seldom seen. Still, there was considerable overhunting of deer in the years during and immediately after World War II. Finally in 1950, only the hunting of male deer was allowed, and all deer hunting was prohibited in seven prefectures including Hokkaidō, Iwate, and Nagano.

This was not sufficient to revive the decimated deer population, however, and in 1978, hunters were limited to killing only one male deer per day. Over the decades of the 1970s and 1980s, deer had become such a rarity that any kind of sighting in the mountains was worth boasting about to anyone who would listen.

Around 1990, however, there was a sudden explosion in the deer population. Around 10 years ago, when Hokkaidō’s Shiretoko Peninsula was declared a World Heritage site, I was driving through the area at night only to be surprised by a huge herd of what seemed like more than 200 deer crossing the road and cutting me off. It was about this time that underbrush on the peninsula was disappearing and trees that had their bark stripped away were dying. The damage was so extensive that people started wrapping the trunks of yew trees and amur cork trees, particularly favored by the deer, with wire netting to protect them.

Today, it is estimated that there are around 600,000 deer in Hokkaidō, the prefecture that suffers two-thirds of the deer damage in the whole country. Deer are even appearing in the towns. They ravage the trees and shrubbery in the gardens of private homes in addition to field crops. I remember seeing a buck with a fine rack of horns on the grounds of Hokkaidō University near the city center of Sapporo. In Hokkaidō alone, there are roughly 2,000 car accidents every year involving deer.

Roadside deer in Hokkaidō. (© Jiji)

Roadside deer in Hokkaidō. (© Jiji)

Prolific Breeders

Deer are voracious eaters. In forests, whether cultivated or natural, they will devour just about any kind of plant, branches, leaves, and fruit, with the exception of a few toxic and thorny plants. In the hard winter months when vegetation is scarce, they survive by eating broad-leaf bamboo grass, fallen leaves, and tree bark. Walk through any forest home to a large number of deer and you will find just about everything eaten as far as the deer can reach, as if the trees had been given bobbed haircuts.

The Environment Ministry’s surveys of Japan’s natural environment and the distribution of large mammals show that from fiscal 1978, when the first survey was made, to fiscal 2014, the distribution of deer has more than doubled. Most notable has been the expansion of their distribution in Hokkaidō, Tōhoku, and the Hokuriku region of Honshū along the Japan Sea coast.

The deer’s ability to bear young every year contributes to the explosion of their population. The natural rate of increase is estimated at between 15% and 20%. At even just 15%, that means a tenfold increase in their number over just 15 years.

Nakajima, a small island in the middle of Lake Tōya in Hokkaidō, is just 5.2 square kilometers in area. Originally there were no deer here, but in the 1960s, one male and two female deer were released onto the island. By 1996, the island had become home to 452 deer. Its dense forest of trees had been eaten away, leaving nothing but barren exposed land. In the winter of 1984, bitter cold and lack of food killed 67 of the island’s deer, but after that their numbers started to increase again. As the grass that had been their main source of food disappeared, they started eating fallen leaves.

A similar population explosion was observed on the island of Okushiri in the Sea of Japan off of Hokkaidō’s southwest coast. Six deer had been released on the island at the end of the 1870s. Roughly two decades later, records show that their number had jumped to 3,000. They were eventually exterminated.

There is a growing fear that if the deer are allowed to proliferate in this way, all of Hokkaidō will soon be overrun just like the Lake Tōya island and Okushiri. In 2014, the Hokkaidō government issued an ordinance for controlling the Ezo deer population.

Why so Many Deer?

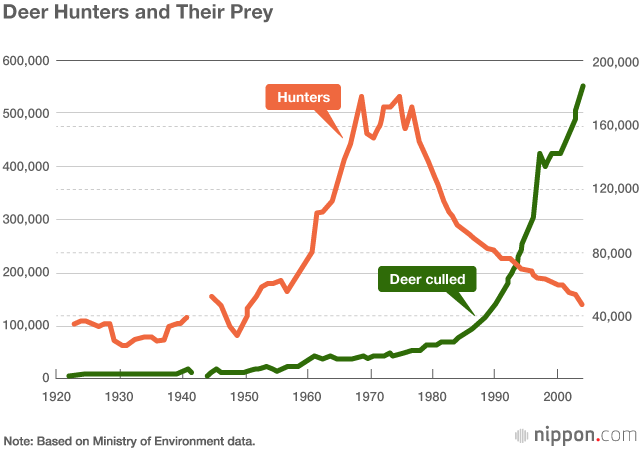

There are a number of hypotheses about these explosions in the deer population. The attribution of cause to a decline in the number of hunters seems logical on the surface, but the facts suggest otherwise. Between 1990 and 2015, the number of licenses issued to hunters (including those for trapping) dropped to only one-third of what it had been, and yet the number of deer harvested increased almost six-fold. This was due to the growing practice of driving the deer into traps and enclosures.

Another hypothesis is that the deer population is growing due to global warming. The argument is that less snowfall means that fawns that would normally have died in the cold winters are now able to survive by migrating. But this doesn’t apply to regions that never get much snow in the first place. Research carried out in Hokkaidō has so far shown no correlation between the amount of snow and the number of deer.

Not a few people support the idea that deer are running rampant because of the drastic disappearance of their natural predator, the wolf. But wolves went extinct in Hokkaidō and on the main island of Honshū way back around 1900—which, indeed, instead prompts the question why there wasn’t an immediate explosion in the deer population after the apex predator’s disappearance.

Groups including the Japan Wolf Association have been promoting the reintroduction of wolves into the wild as a way to control the Ezo deer population. In the United States, I was present for the 1995 release of wolves brought from Canada into Yellowstone National Park, where they had vanished. The wolves have helped to revive the ecosystem in the park. Similar action is being contemplated now in Germany, Italy, and other countries plagued with growing deer populations, but Japan still has a number of constraints that makes this difficult.

The Bounty of Forest Expansion

Finally, there is the hypothesis that the number of deer has burgeoned not only because they were protected by hunting limits, but also because of Japan’s program to expand its woodlands. In the 1950s and 1960s, there was a surge of forest plantings throughout Japan as native forests of Japanese beech and other deciduous trees were cut down and replaced by new seedlings. In all, more than 40% of the country’s native woodland was replaced by planted forests.

The newly planted forest land offered succulent saplings and young trees, and the felling of native forests created large swaths of sunlit areas where fresh grass was quick to grow. Things couldn’t be better for the deer, which normally prefer open forest areas and fresh greenery—they were receiving an ideal ecological environment.

The new-planting program peaked in 1970, and has since plummeted to less than a twentieth of its scale then. Planted forests need to be tended constantly to ensure good lumber. Groves need to be thinned, branches lopped off, and undergrowth cut back. In 1964, however, the government lifted restrictions on lumber imports, causing the price of lumber to plummet. Along with the declining numbers of forestry workers, this accelerated the abandonment of many of the replanted forests.

Timberland owners, discouraged by the trend, increasingly left their holdings untended. The numerous cryptomeria (Japanese cedar) and cypress trees planted under the reforestation program mature in 35–50 years and need to be harvested, but they have been left to continue to grow and, in fact, are increasing in number. The cryptomeria stands, in particular, have become a major cause of pollen allergy throughout Japan. The abandoned forests are full of underbrush, low shrubbery, and branches that offer even more food to foraging deer.

The conservationist and ecologist Takatsuki Seiki, meanwhile, believes that the increase in pastureland that Japan has seen as its planted forest land has dwindled is providing deer with a new habitat. Pastureland that covered about 81,000 hectares in 1961 has remained steady at around 600,000 hectares since 1980. And true enough, deer have become a common sight on Hokkaidō pastures. The rich banquets of nutritious grass must surely be impossible to resist.

Saplings protected from marauding deer with white netting in Kobuchisawa, Yamanashi Prefecture. Damage caused by deer is a serious problem on the main island of Honshū. (© Moriya Yoshihiko, member, Kantō Branch, All-Japan Association of Photographic Societies)

Saplings protected from marauding deer with white netting in Kobuchisawa, Yamanashi Prefecture. Damage caused by deer is a serious problem on the main island of Honshū. (© Moriya Yoshihiko, member, Kantō Branch, All-Japan Association of Photographic Societies)