Communication and the Japanese Language

A Warning About Japan’s Future? AI Outperforms Students at Reading

Society- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

The Limits of AI

“Can a Robot Get into the University of Tokyo?” If you heard the name of this project, you would be forgiven for thinking that the aim was to get a robot to pass the prestigious institution’s entrance examinations. Project leader Arai Noriko of the National Institute of Informatics explains, however, that the goal was not to show what an artificial intelligence could do, but rather what it could not—to clarify the limits of AI compared with humans.

After some six years of research, the AI ultimately failed to pass the test, but posted a deviation score of more than 57, putting it in the top 20% of final-year high school students. This means it would be able to pass the entrance exams for some famous private universities. However, it did not solve questions by understanding the meaning of words. For example, Tōrobo-kun, as the AI is called, wrote essays by searching textbooks and Wikipedia, picking out and arranging sentences, and then polishing the text. The result was better than most students’ essays. How could an AI that is unable to read and understand sentences perform better than a human? In pondering this question, Arai began to wonder about the reading ability of students in seventh through twelfth grade.

Assessing Students’ Reading

Arai developed a Reading Skill Test, which has been taken by more than 40,000 students since April 2016. She says it is very unusual for a noncompulsory survey to receive this level of response.

The test includes six types of questions: identifying what demonstrative pronouns like sore (that) and kore (this) or omitted subjects and objects are referring to (anaphora), identifying the subject and object (syntactic dependency), inferring from sentences based on logic and common sense, judging which specific actions or things would fit a given definition, judging whether two sentences have the same meaning, and identifying which diagram matches a sentence. The questions are based on materials in the junior high school and high school textbooks, as well as dictionaries and newspapers. If students cannot read and understand the questions, they cannot read and understand these other everyday texts.

“Since I started writing an introductory mathematics textbook, I have frequently visited junior high schools. I eat lunch together with the students and talk to them, so I can learn from what point they find it difficult to understand. In San’ya, Tokyo, where there are many cheap lodging houses, I went every week to a meal center for two years and saw where people tripped up. This is all connected with the RST.”

Good and Bad Questions

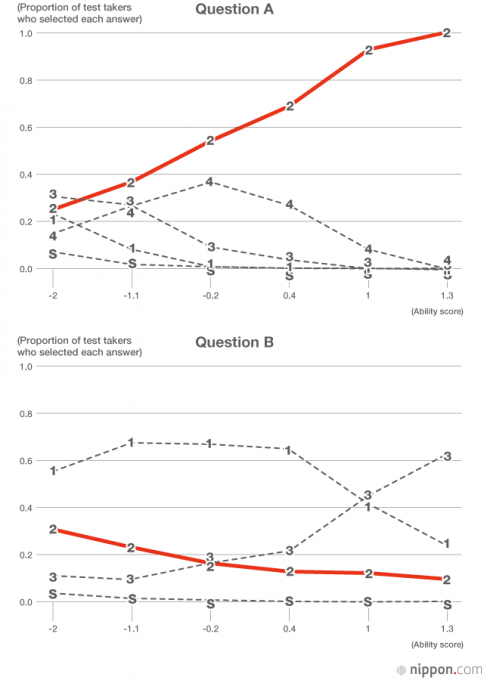

Questions are assigned to test takers at random. As different students tackle different questions, it is not possible to grade simply on the number or percentage of correct answers. Instead Arai applies item response theory, which is used in many assessments, such as the popular TOEFL, or Test of English as a Foreign Language. IRT provides an estimate of test takers’ overall ranking for each question type. For example, there might be two questions (A and B) with four possible answers to select from. In both cases, the correct answer is option “2.” Setting ability score on the x-axis and the proportion of test takers who selected each answer on the y-axis gives the following graphs.

With question A, the higher the ability score of the test taker, the more likely he or she is to choose the correct answer. This is therefore a good question for measuring ability. With question B, however, as ability score rises, the proportion who pick the right answer actually drops. As there is also not a great difference between the proportion of correct answers from people with low and high ability scores, this is not a good question for assessment.

Before final analysis in the RST, questions like these are identified and deleted. In computerized tests, it is possible to examine the link between the speed of answering and the percentage of correct answers to discard the results of test takers who have probably just answered at random without actually reading the questions. These are just a few examples of the question analysis and assessment methods used in the RST.

The correct answer percentage is calculated based on the number of questions that students tackle. If they only answer three questions, the ratio is worked out from just these three. Before taking the test, they also try example questions and see the correct answers, so they can understand the nature of the questions in advance.

Not Much Better Than Random

“Alex” is a name used for both men and women. For women it is a nickname for “Alexandra,” while for men it is a nickname for “Alexander.”この文脈において、以下の文中の空欄に当てはまる最も適当なものを選択肢のうちから1つ選びなさい。

Choose the correct word from the options below to complete the following sentence.Alexandraの愛称は( )である。

Alexandra’s nickname is ( ).

①Alex ②Alexander ③男性 ④女性

1. Alex 2. Alexander 3. Men 4. Women

The correct answer is 1, chosen by 37.9% of junior high school students and 64.6% of high school students.

In 1639, the shōgunate expelled the Portuguese and ordered the daimyō to guard the coasts.上記の文が表す内容と以下の文が表す内容は同じか。「同じである」「異なる」のうちから答えなさい。

Does the below sentence have the same meaning as the above sentence? Answer “same” or “different.”

1639年、ポルトガル人は追放され、幕府は大名から沿岸の警備を命じられた。

In 1639, the Portuguese were expelled and the shogunate was ordered by the daimyō to guard the coasts.

The correct answer is that the meaning is “different,” chosen by 57.4% of junior high school students and 72.3% of high school students. As there are only two possibilities, junior high school students performed only slightly better than the 50% success rate that would be achieved by flipping a coin to pick the answer.

The RST reveals the proportion of test takers who cannot perform better than answering at random. This was around half for making inferences, giving specific examples for a definition, and judging whether two sentences have the same meaning. Even in such basic areas as anaphora and syntactical dependency, some 15% of students could not score better than if they had relied on chance alone. The RST further demonstrated a strong correlation of 0.8 between estimated basic reading ability via the test and high school entrance examination scores, which is around the same level as that between height and weight. Students who can read well tend to go on to good high schools. Reading ability is an essential prerequisite for academic ability in general.

People Can Change

Arai wants it to be possible for all students to take the RST for free in their first year of junior high school and for them to all be able to thoroughly read and understand the textbooks before they graduate. If boards of education agree to pay for RST training for teachers, she says she will provide free tests for junior high school students in their first year.

“When I realized that students were not able to read their textbooks, I had two options. The first was to think, ‘Textbooks are full of bad writing. It doesn’t matter if they can’t read them.’ The alternative was to think, ‘I have to do something about this.’ Which has the greater potential? I can’t persuade everyone who thinks it doesn’t matter. This is why I want to help by diagnosing reading levels in the first year of junior high school, so teachers can understand the reality and work to improve the students’ reading levels.”

According to some RST data, basic reading ability improves slowly during junior high school, but does not get better in high school. But Arai says, “That’s definitely not true.” Why would a mathematician doubt the data?

“At university, where I studied law, in a criminal law class I heard a talk from a woman who was the defendant in a famous case of wrongful conviction. She spoke so logically, I wondered how the police could have blundered by arresting her. But then I thought later that she had changed through her experience in the courts, where only language and logic could help her clear her name. People can change. So it’s important not to give up too easily.”

A Dream of Making Her Test Redundant

In her 2010 book Konpyūta ga shigoto o ubau (Computers Will Take Our Jobs), Arai predicted that in 2030 AI would perform half of all white-collar jobs. For the children of today to stay employed as adults, they must be better at understanding meaning than AI.

“The students who can do the RST say, ‘The answers are written in the question. It’s so easy I don’t know what you’re testing.’ The ones who have no idea say, ‘These questions were different from usual, so I didn’t understand,’ or ‘There wasn’t anywhere near enough time.’ Meanwhile, the middle ranks say, “They’re trick questions. I overthought them and gave some wrong answers.” They really aren’t trick questions at all, though. The students who say that may be mad at their mistakes. If they are, I think that’s the first step to changing. If students in ninth grade, the final year of junior high, can get 80 percent of the questions right on the RST, Japan is safely ready for 2030. I hope that this happens and the RST becomes unnecessary. It would be good if our precious and increasingly rare children can all read fluently and achieve their dreams.”

(Originally published in Japanese on March 6, 2018. Reporting and text by Kuwahara Rika of Power News. Photographs by Imamura Takuma. Banner photo: Arai Noriko of the National Institute of Informatics.)