A Japanese Psychiatrist’s Takes on the Trials of Life

Overcoming the Fear of Solitude

Society- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Distracted Lives

We live in an age in which we rarely feel materially deprived, and our lives are considerably more comfortable than in the past. Strangely enough, however, the number of people who feel a vague sense of emptiness has grown in inverse proportion to this material repletion. Even acquiring a wanted item or product only provides diversion for a limited time and the sense of emptiness is never entirely gone.

A succession of tools has been developed to meet modern humans’ desire for temporary diversion. These tools are beguilingly designed to keep us stuck to them, thereby allowing us not to confront our inner void during our unoccupied intervals.

In the recent past, television was the prime such tool, but now smartphones play the leading role. It has become common to see people riding trains and walking the streets with their eyes glued to their phone screens. Some do not even look up when crossing at a traffic light.

Why are we so desperate to spend our precious time distracting ourselves like this?

Solitude and the “Two-in-One” State

The motivation for this frantic effort to fill our unoccupied intervals is the desire not to sense that we are solitary beings. Scared of solitude, we strive to fill our hours and minutes however we can.

Is solitude really so frightening?

German-born philosopher Hannah Arendt (1906–75) distinguished three types of aloneness: solitude, loneliness, and isolation. Loneliness is a painful feeling of disconnection from both others and oneself. Isolation is a sense of absorption in some form of activity that cuts the connections with others and oneself. But Arendt takes a highly favorable view of solitude, which she says makes possible a “two-in-one” state. What does she mean by this?

To answer this question, first we must understand the nature of our underlying system as human beings.

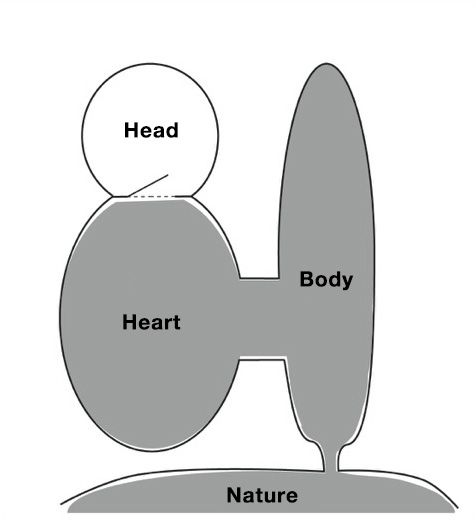

Diagram 1.

Diagram 1.

The Human System

The head: home of reason

The heart: home of emotion, desire, and sensation

Feeling that the conventional representations of the human state used in psychology did not adequately express the various phenomena that occur within us, some time ago I came up with the interpretation shown in diagram 1. It has proved quite useful in psychiatric treatment, and I believe it is also easy for ordinary people to understand, so I would like to use it in my explanation.

The foundation of our existence, just like that of other animals, is the heart/body pair, which is governed by the principles of nature in the wild. But our system as humans is a hybrid one; the head (brain) above our heart/body has developed through evolution into an information-processing center that operates on a different set of principles .

The head is equipped with language as a tool, and it uses computer-like processing power to run all kinds of simulations and comparisons. This allows it to deal with the past, using processes like analysis and reflection, and with the future, using processes like prediction and planning. But it has a hard time coming to grips with the present. It tends to seek control over events with words like “must” and “should.” And when its efforts fail to work as desired, it locks the door between itself and the heart.

The heart, on the other hand, is permanently and inextricably connected with the body, and there is no possibility of contradiction between the two. The heart/body pair always reacts intuitively and immediately to the here and now. Its actions are not governed by the logic and reasons of the head but are driven by what it does or does not want to do, .

Let us now reconsider Arendt’s two-in-one state. It is a combination of the head and the heart/body, operating on non-natural and natural principles, respectively. Thus, people contain two basic selves.

If the head locks its door to the heart, it becomes captivated by external relationships—obsessed with how it connects with others and what they think of it. There is the same kind of disconnection with the self as that described above for loneliness and isolation.

Tapping the Shared Current of Truth and Beauty

In the case of solitude, however, the head leaves its door to the heart open, allowing for a rich and lively two-in-one state. When people are moved by something, hit upon a new idea, or enter deep contemplation, it is always in solitude.

As diagram 1 shows, listening to the heart/body means linking oneself to the broad realm of natural providence extending beyond this pair. This realm includes what we might call a subterranean water vein. It is a bountiful current of wisdom that all humans can tap.

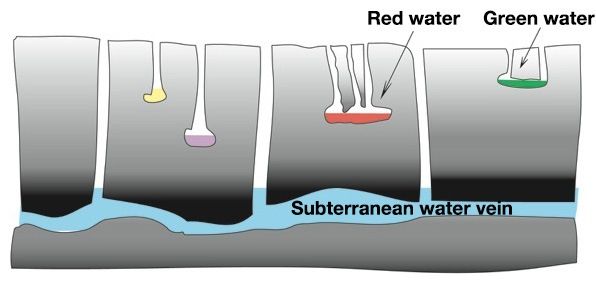

Diagram 2. Delving Toward the Subterranean Water Vein

Diagram 2. Delving Toward the Subterranean Water Vein

Developing the metaphor further, diagram 2 illustrates how people’s perceptions vary depending on how deep they delve. A person who digs to one level may find a pool of green water, for example, while one who digs to another level may find the water to be red. Both will confidently declare their respective findings. But if we go down far enough we will hit the subterranean water vein from which we can draw truth and beauty that transcends specializations and individual traits.

Inspiration does not arise from calculation in the head; it comes from ideas that pop up without notice from the heart/body. These are made possible by the connection through nature to the subterranean water vein. All the myriad artistic and literary visions, philosophical and scientific discoveries, and technological innovations of humankind are universals drawn to the surface through this connection.

Solitude makes it possible for us to connect directly to the subterranean vein, which is a far more bountiful source than what we can derive by linking superficially to others or accessing existing information. So it is most certainly not a condition to be feared as a source of unease.

Unless we have intervals of emptiness we cannot experience solitude, and without solitude we cannot conduct precious dialogue with ourselves. Without internal dialogue, frantic attempts to avoid empty intervals by using tools like social media only result in isolation. The smartphone may distract us, but it cannot erase the hollowness and loneliness lurking inside us. The sense of hollowness comes not from a lack of connections with others but from the inability to connect with ourselves.

Take a little courage to cut back on the distractions and open up some empty intervals. Set aside the fear of solitude and try entering into a quiet conversation with the other “me” you will find inside. This will let you start living a life that is truer to yourself—and one day you will surely experience the ultimate joy of tapping the great subterranean vein of wisdom.

(Originally published in Japanese on March 23, 2018. Banner illustration by Mica Okada. Diagrams by Izumiya Kanji.)