Ogasawara Islands: 50 Years After Reversion

Reflections on Ogasawara: Remote Islands with American and Japanese Identities

Society Culture- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

One History, Two Names

Japan’s remote Ogasawara Islands have enjoyed an uptick in tourism since being registered as a UNESCO Natural World Heritage Site in 2011. Visitors from Japan and abroad now regularly venture to the volcanic chain, floating in the Pacific Ocean some 1,000 kilometers south of Tokyo, to admire the uniquely evolved plants and wildlife and to view the dolphins and whales that approach its rustic shores.

Dig a little deeper into the history of the human settlements on these distant islands, though, and one finds that despite being Japanese territory, they have deep Western roots.

Originally called the Bonin Islands, a name thought to derive from the Japanese terms muninshima or buninshima, meaning “uninhabited islands,” the picturesque archipelago was first settled in 1830 by a motley band of Americans, Europeans, and Pacific Islanders. The group under the leadership of Nathaniel Savory, a native of Massachusetts in the United States, built an early settlement on the island of Chichijima into an important stopover for merchant and whaling vessels plying the Pacific, placing the previously unclaimed island and its associated chain on the map.

Successive generations of inhabitants built a unique culture infused with Western, Pacific Island, and Japanese customs and linguistic influences. Despite the remote location of the Ogasawaras, the islands over their nearly 200 years of inhabitation have endured a surprisingly tumultuous history.

The early settlers were largely independent, but in 1876 Japan gained possession of the Bonins. Tokyo subsequently renamed the chain the Ogasawara Islands and forced non-Japanese inhabitants to take Japanese citizenship. During World War II, descendants of the original settlers, known locally as Ōbeikei (Westerners), were evacuated along with other islanders to the Japanese mainland. The US Navy took control of the islands at the end of the war, when Ōbeikei residents, but not their fellow Japanese islanders, were allowed to return in 1946. A little more than two decades later, in June 1968, the Bonin Islands again reverted to Japanese control.

Since then the Ōbeikei community has continued to dwindle due to a variety of demographic factors, leaving only a handful of residents to share the islands’ rich culture and history. Two islanders descended from the first Western settlers who are keeping the old memories alive are the mother-son pair of Ōhira Kyōko and Rance Ōhira.

In Calm and Storm

Kyōko was born in 1921 on the main island of Chichijima. Growing up she enjoyed a peaceful childhood before living through the war years, when the islands’ residents were evacuated to the mainland. She started life as Edith Washington, but like other islanders of Western descent she was required to take a Japanese name.

Ōhira Kyōko, who also goes by the English name Edith Washington, is an Ōbeikei resident of Chichijima.

Ōhira Kyōko, who also goes by the English name Edith Washington, is an Ōbeikei resident of Chichijima.

“I was staying for a stint on the mainland when I received a telegram from Chichijima ordering me to change my name,” she recalls. “I remember being given several choices and told to select a simple family name to make filing paperwork easier, so I decided on Ōhira.” Asked which name she feels suits her best, she chuckles that “I’ve been called both for so long that I hardly notice which one people are using.”

When growing up, Kyōko says that life in the Ōbeikei community on Chichijima was dominated by Japanese culture. ”We spoke in Japanese,” she explains, “and the adults would even go out after work dressed in casual yukata.” The local school had a teacher, sent specially from Tokyo, who taught how to sew Western-style clothing and Japanese attire like hakama trousers and instructed students in making Japanese handicrafts and doing housekeeping. “I enjoyed learning these skills,” Kyōko declares. “I even studied how to put together a futon. It was a good time to live on the island.”

However, the start of World War II brought an end to the carefree life she enjoyed. As the conflict progressed the authorities evacuated islanders to the mainland, turning the Ogasawaras into a military outpost. Kyōko and others from the community were put to work at a munitions factory in Tokyo, where they labored for nearly a year. Although separated from her home, Kyōko says she found solace in companionship. “Those of us from the islands lived together in company housing, so I wasn’t lonely. But life was hard. I can’t say how overjoyed I was when the war ended and we were allowed to go home.”

Kyōko returned to Chichijima in 1946, while it was under control of the US Navy. Although the war had left much of her old neighborhood in ruins, including her family’s home, she quickly set to work rebuilding her life. “Things had changed a lot,” she recalls, “but with the help of the American servicemen we were able to get by well enough. They even rebuilt the school, which was a blessing.”

Kyōko looks through an old photo album from the prewar and wartime years.

Kyōko looks through an old photo album from the prewar and wartime years.

A Long-Awaited Return

Life on the island during the occupation was strongly influenced by restrictions imposed by the US military. Only Ōbeikei residents had been allowed to return, and entrance to the island was limited to navy personnel. “It was tough being apart from friends I had grown up with,” Kyōko laments. Having lost contact in the postwar confusion, she did not even have addresses where she could send letters.

In the late 1960s, though, the radio brought the news that the island chain would be returned to Japan. This meant that after more than two decades, the islanders of Japanese descent could come home at last. “I had longed to see my friends for so many years,” Kyōko recalls. Overwhelmed with joy at the announcement, she let her feelings flow. She jotted her thoughts about friendship and the island’s past on a stray piece of stationery, which she carried in her pocket for comfort until the handover. The contents of the note would later be set to music and titled “Reversion Song.”

Kyōko, a talented singer of ballads from the islands, says that the joy she felt on that day comes rushing back when she performs the song. “Being reunited with my friends on the island was one of the happiest moments of my life.”

Although she has been forced at times to choose between her American and Japanese identity, Kyōko never doubted her Ogasawara roots, asserting firmly that “I am an islander.”

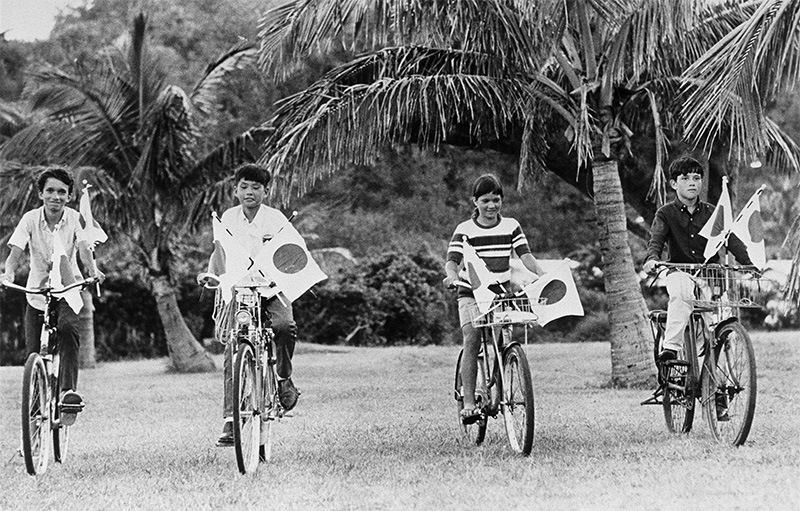

Children on Chichijima display Japanese flags to celebrate the reversion of the Ogasawara Islands on June 26, 1968. (© Jiji)

Children on Chichijima display Japanese flags to celebrate the reversion of the Ogasawara Islands on June 26, 1968. (© Jiji)

Caught in the Middle

The Okumura district on Chichijima was once called “Yankee Town” for its thriving Õbeikei community. Rance Ōhira, Kyōko’s son, runs a bar in the area by the same name that keeps the memories of that fading era alive. “It took three years to build the place from scratch,” he proudly exclaims, a smoldering cigarette between his fingers.

Rance Ōhira’s bar Yankee Town is just a short walk from the town center.

Rance Ōhira’s bar Yankee Town is just a short walk from the town center.

Rance mixes a drink at the bar.

Rance mixes a drink at the bar.

Born on Chichijima in 1950 while the island was under US Navy administration, Rance, who began life as Rance Washington before later taking the family name Ōhira, remembers growing up with a foot in both Japan and America. “I spoke Japanese with my mother,” he recalls, “English at school, and a mixture of both with my friends.” Although there were inconveniences, he says life during the occupation was relatively easy. “I would go hunting wild boar in the forest with my father and friends to help put a little extra meat on the table, or hop into a canoe and paddle off to catch fish. We would choose our clothes from the Sears Roebuck catalog and then have to wait and wait for them to arrive. But life was good. The US Navy provided daily necessities, handled our schooling, and even helped rebuild people’s houses.”

Rance says that for a young boy, living among Chichijima’s rich natural environment was like paradise. However, this free, idyllic lifestyle abruptly ended when he finished the seventh grade, the last year at the local school. To continue schooling, Rance and his classmates had to transfer to the US island of Guam. He remembers his excitement about leaving Chichijima for the first time, but life on Guam had its own challenges. “There were lots of things that got under my skin, like how the other students would talk down to us because we weren’t from the island.”

With no other options for education, Rance remained in the US Territory. However, when he reached the eleventh grade, the Ogasawara Islands reverted to Japan, forcing him to choose whether to remain in his current life or to return home. “It was already my plan to come back after I graduated,” he says. “But since a high school had been built on Chichijima it made more sense to spend my last year of school on the island where I could study the Japanese language in earnest.”

On June 26, 1968, the day of the handover, Rance boarded the last flight from Guam bound for the Ogasawaras.

The Prodigal Son

After graduating Rance began work, but quickly found that life on the island had changed from the free and easy days of his childhood. New Japanese-style administrative structures had displaced the old systems. The Japanese government has also declared the Ogasawara chain a national park, bringing a slew of regulations like a ban on hunting and turning large swaths of the island into specially protected reserves. Rance resented seeing the island of his boyhood slowly fade away and chose to move to the United States.

After living in the United States and serving in the US military, Rance returned to Chichijima in 1994.

After living in the United States and serving in the US military, Rance returned to Chichijima in 1994.

Rance says his connection to American culture influenced his decision. ”When I was born, the island was under US control and all my schooling had been in English. Chichijima had become foreign to me, so I decided to head to the United States and join the military. I wore my uniform with pride—for the first few years, at any rate.”

Rance took US citizenship and lived in America for close to 20 years. All the while, though, the Ogasawara Islands continued to call to him. “I might not have consciously thought it, but I knew I would return someday. There’s no escaping the fact that I’m a Bonin Islander.”

Rance returned to Chichijima in 1994 and set about building his bar in the old Ōbeikei neighborhood to keep the Yankee Town name alive. Like his mother, he has come to embrace his islander roots.

The islands have struggled under the pressures of war and the whims of Japanese and American governmental policies. This tumult, though, has strengthened the identities of both mother and son as proud islanders and Ōbeikei.

This year marks the fiftieth anniversary of the reversion of the Ogasawara Islands to Japan. Since that historic moment, the islands have continued to change as young people move in from the mainland, bringing with them new ideas about the future. As a consequence, the Ōbeikei culture is slowly being forgotten. While change is inevitable, the spirit of the Bonin Islands will live on as long as there are people like Kyōko and Rance to share the memories and history of those bygone days.

(Originally published in Japanese on June 25, 2018. Banner photo: Rance Ōhira at his bar Yankee Town on Chichijima. All photos by Iseki Tsuyoshi unless otherwise noted.)