Ogasawara Islands: 50 Years After Reversion

A Modern History of the Ogasawara Islands: Migration, Diversity, and War

Society- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Islands With a Unique History

June 26, 2018, marks exactly 50 years since the United States returned control over the Ogasawara Islands to Japan.

The islands in question mean the Ogasawara Islands broadly defined, comprising the Bonin Islands (the two main islands of Chichijima and Hahajima and a number of smaller surrounding islands, located roughly 1,000 kilometers to the south of Tokyo), together with Minami-Torishima (Marcus Island), 1,300 kilometers east of Chichijima, and Iwo Jima (Iōtō) and the other Volcano Islands, more than 200 kilometers south of Chichijima.

Since they returned to Japanese sovereignty, the Ogasawara Islands have been under the authority of the Tokyo Metropolitan Government. According to some calculations, the Ogasawara administrative region accounts for more than one third of Japan’s total exclusive economic zone.

Since becoming a UNESCO world heritage site in 2011, the islands have become well known for their pristine natural environment. But even in Japan, not many people are aware of the unique and complex history of the islands. (For more on this history, see “An Ogasawara Chronology: From Settlement to UNESCO World Heritage Listing.”—Ed.)

Commodore Perry and John Manjirō: Plans for Annexation

Until the early nineteenth century, the islands were uninhabited, although people occasionally stopped there for short periods. Permanent settlement began in 1830, when a group of around 25 men and women from Oahu in the Hawaiian Islands arrived in Chichijima in the expectation of growing demand for commerce. The first settlers were a mixture of Europeans, North Americans, native Hawaiians, and other Pacific Islanders.

The first inhabitants farmed vegetables, grains, and potatoes, raised livestock, and fished for sea turtles. They supplemented their livelihood by selling fresh food to sailors who used the islands as a stopping point during long ocean voyages.

The early to mid-nineteenth century was the height of the whaling industry throughout the Pacific, driven by demand for oil for lamps. In the 1820s, whalers from the United States began to expand into the northwestern Pacific, but with Japan still isolated under the Tokugawa shōguns, finding safe harbors in which to replenish supplies in Japan or the Ryūkyū Islands was not easy. The Bonin Islands therefore made an attractive place for large ships to stop and replenish supplies.

For around half a century after the first settlers arrived, the Ogasawara Islands were not under the formal sovereignty of any nation. In the 1850s, Matthew Perry, commander of the US Navy’s East India Squadron, passed by Chichijima with his famous fleet of “black ships” on his way to Uraga and planned to incorporate the islands as US territory.

In the 1860s, the shogunate sent a delegation with the legendary castaway John Manjirō as interpreter in an attempt to claim the islands as Japanese territory. But attempts to settle the islands from Japan met with setbacks and were soon abandoned.

In the years that followed, a diverse range of people arrived on the two main islands: deserting sailors who fled harsh conditions by jumping ship while in port, people forced to land because of illness or injury, shipwreck survivors, and pirates who came ashore intent on robbing the islanders of their money or women.

The islanders’ ethnic backgrounds were similarly diverse, reflecting the origins of sailors on whaling vessels at the time: alongside Europeans, there were people from islands all around the Pacific, Indian, and Atlantic Oceans.

The Ogasawara Islands were on the front lines of the globalization taking place throughout the Pacific in the nineteenth century, as sailors came ashore and settled down. The islands were an autonomous space that encapsulated in miniature the global society of the time.

Incorporation Under the Japanese Empire and Population Boom

In 1876, the Meiji government succeeded in annexing the islands as Japanese territory, with the consent of the Western powers. All the “foreign” residents of the islands were naturalized as Japanese subjects by 1882. But the Japanese authorities continued to be suspicious of these naturalized “foreigners,” and regarded them as requiring special supervision for security reasons.

From then until the early years of the twentieth century, the population grew rapidly, fueled by an influx of migrants from the Japanese main islands and the Izu Islands. The economy of the islands was booming, with sugarcane farming and sugar refining the main industries. The Ogasawara Islands were a model of successful colonization as the Japanese government planned expansion further into what it called Nan’yō, the Pacific Ocean south of Japan.

During the second half of the 1920s, sugar prices collapsed on the world market. Farmers in the Ogasawara Islands managed to overcome the crisis by diversifying. Using the warm sub-tropical climate of the islands to their advantage, they produced summer vegetables during the Japanese main islands’ winter, at a huge profit. The 1930s were a golden age for the economy of the islands.

In 1891, the Japanese government had declared Japanese sovereignty over the Volcano Island chain. By the 1910s, they had established an economy, centered like the Ogasawara Islands on sugar cane cultivation and sugar refining. Migrants came to the island from the main islands as well as the Izu Islands, Chichijima, and Hahajima. Again, economic diversification took place in response to the slump in sugar prices during the 1920s, and for a while the island specialized in unusual niches, cultivating coca leaves and using them to produce cocaine.

Unlike on Chichijima and Hahajima, where most of the settlers were independent smallholders, the majority of the people who came to the Volcano Islands were employed by a company established to manage colonization there. These farmers had to grow crops designated by the colonization company, which then shipped the produce in bulk to the Japanese mainland. They had to purchase all their daily necessities from local shops related to the same company. The Volcano Islands were home to an exploitative plantation society, in which the colonization company controlled every aspect of the farmers’ economic and daily lives. However, a blind eye was turned to informal work like fishing and livestock farming, and in the mild climate, the farmers at least had no need to worry about meeting their basic needs for food, clothing, and shelter.

On the Front Lines of the Pacific War: Evacuations and Refugees

In the 1920s, the Japanese Army established a “fortification headquarters” on Chichijima and the militarization of the Ogasawara Islands began, in the context of an imagined conflict with the United States. A naval airfield was built on Iwo Jima in 1932.

In 1944, as the war entered its final stages and US forces swept through Micronesia, the Japanese armed forces ordered a forced evacuation of roughly 7,000 of the 8,000 civilian noncombatants then living on the Ogasawara Islands and Iwo Jima. The islanders had to leave behind their property and everything they needed for their daily lives, except a few small personal effects. They essentially became refugees.

Most of the few remaining men aged from 16 to 60 were exempt from the evacuation and were instead pressed into working for the military on the islands. In February 1945, when the US Marines landed on Iwo Jima, 103 civilians were working on the island as workers attached to the military.

According to Japanese government statistics, around 22,000 people on the Japanese side were listed as killed or missing in action on the Japanese side in the battle for Iwo Jima, along with around 6,800 American dead. Of the civilians mobilized to help defend the island, just 10 survived.

In the course of the defeat, the Japanese came to regard the Ogasawara Islands as the last line of defense for the mainland, leading to terrible suffering for the inhabitants.

Cold War Reconstruction and Exclusion

After the Japanese defeat, the Ogasawara Islands were placed under the direct control of the occupying US forces. In 1946, the US allowed islanders of “Western” descent to return to Chichijima—around 130 people returned following this decision, descendants of the original islanders who had lived on the Ogasawara Islands before they were incorporated into Japanese territory.

In 1951, with the Cold War intensifying in East Asia, the San Francisco Peace Treaty was concluded. Article 3 of the treaty decreed that the Amami Islands and Okinawa Islands, together with the Ogasawara Islands, would remain under the authority of the United States, with the consent of Japan. Japan succeeded in regaining its sovereignty by offering the Ogasawara Islands for the use of the US military.

The “Western” population who had returned to the islands were able to make a living as civilian workers on US military facilities. Meanwhile, the United States secretly placed nuclear warheads on Chichijima and Iwo Jima.

But most of the islands’ former population were still not allowed to return. A movement started, campaigning for the right to return to the islands and demanding compensation from the government. But with many of the islanders struggling with poverty and exile on the mainland, there were repeated incidents of suicide, with whole families sometimes taking their lives together in desperation. The islanders were used as a steppingstone for national reconstruction and rebuilding in the immediate after-war years.

Finally, in 1968, responsibility for the islands was handed back to Japan and the US Navy withdrew. After a quarter of a century in exile, the islanders were finally allowed to return to their homes on Chichijima and Hahajima. In Iwo Jima, however, the Japanese government stationed members of the Self-Defense Forces on the island as soon as the US armed forces left. The government excluded the Volcano Islands, including North Iwo Jima island from national reconstruction plans, and in effect blocked any return of the islanders to their former homes. In 1984, an advisory body to the National Land Agency (now the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport, and Tourism) advised that settling a civilian population on Iwo Jima would present serious difficulties, due to reasons it claimed as “volcanic activity” and “unexploded military ordnance” left over from the war.

In 1991, the Japanese government transferred most of the field carrier landing practice for its carrier-based aircraft based out of the US naval base in Yokosuka from the Atsugi airfield in Kanagawa Prefecture to the SDF airfield on Iwo Jima.

The Sacrifices Behind the Natural Beauty

In the 1990s, Chichijima, the economic center of the Ogasawara Islands, became a prime destination for ecotourism in Japan. In 2011, the Ogasawara Islands were included on UNESCO’s World Heritage list. The islands’ fauna and flora include many endemic species, and the natural ecosystem is remarkably well preserved—these were the reasons for the islands’ inclusion on the list.

But the islands’ status as a World Heritage site was built on the very real human sacrifices of the people who lived on the islands before the war, and who were forced to become refugees while the islands were used as a secret military base during the Cold War. The US armed forces did not develop the islands except for the immediate vicinity of its military facilities, and left the natural environment untouched. And today, even 74 years after they were forced to evacuate, there are still no prospects that the former inhabitants of Iwo Jima will ever be allowed to return home.

The population of the Ogasawara Islands have been subject to massive state interference and control. As we mark the fiftieth anniversary of the islands’ return to Japanese sovereignty, I hope that more will be done to share the story of the islands’ unique and complex history with people in Japan and around the world.

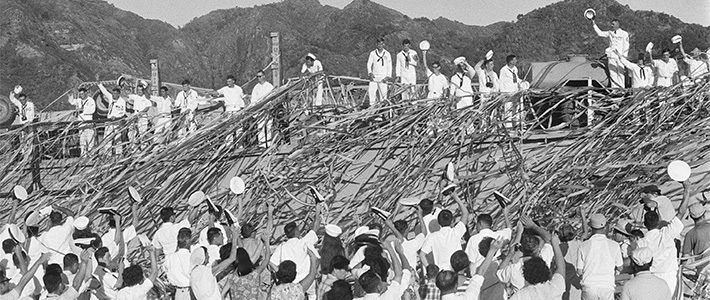

(Originally published in Japanese on June 26, 2018. Banner photo: US forces prepare to depart for repatriation on a navy vessel while islanders watch on at Chichijima on June 27, 1968.)