Yasukuni Shrine: the Basics

Politics Society- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

The Origins of Yasukuni

Statue of Ōmura Masujirō within Yasukuni Shrine. © Fujifotos/Aflo

Statue of Ōmura Masujirō within Yasukuni Shrine. © Fujifotos/Aflo

Yasukuni Shrine has its beginnings in a proposal by Takasugi Shinsaku (1839–67), a samurai who played a key role in the 1865 civil war in the Chōshū domain that helped bring about the 1868 Meiji Restoration, for a shōkonsha—a shrine dedicated to the spirits of the war dead—to honor members of Takasugi’s Kiheitai militia who had fallen in the fighting against the pro-shogunate forces. Following the 1868 Boshin War, a ceremony took place at Edo Castle (now the site of the Imperial Palace) to honor the spirits of the pro-imperial forces hailing from the western Japan domains of Satsuma, Chōshū, Tosa, and Bizen. Concurrently, the souls of the lost soldiers were enshrined in the Higashiyama district of Kyoto.

This touched off a nationwide movement to honor and console the spirits of those who had perished in the Meiji Restoration struggles. Ōmura Masujirō (1824–69), the “father of the modern Japanese army,” recommended that Emperor Meiji establish a shōkonsha in Tokyo. The emperor responded in 1869 by founding the Tokyo Shōkonsha in what is today the Kudanshita area of central Tokyo, and 3,588 souls of the Boshin War dead were enshrined together—a process known as gōshi. Construction of the shrine was completed in 1872, and it was renamed as Yasukuni in 1879. (No actual remains are interred at Yasukuni; the shrine is a place of repose for the souls of the dead.)

The aim of the shrine was originally to honor only those who had fallen in battle while fighting for the sake of the emperor. This means that famous military figures including Saigō Takamori (1828–77), killed in battle while opposing the Meiji government in the Satsuma Rebellion, and Etō Shinpei (1834–74), who had launched the Saga Rebellion in 1874, were branded as rebels and not included in the honored souls at Yasukuni. Members of the famed Byakkotai, or “White Tiger Squad”—who fought against the Meiji government in battles in the Aizu domain (today’s Fukushima Prefecture) and committed suicide when faced with inevitable defeat—have similarly been passed over for enshrinement.

This does not mean that the shrine’s gōshi policy has been applied consistently through the years. Yoshida Shōin (b. 1830) and Hashimoto Sanai (b. 1834)—both executed in 1859 as part of the Ansei Purge carried out by the Tokugawa government against opponents of its trade treaties with foreign powers—are both enshrined at Yasukuni, despite their deaths coming well before the Boshin War. Takasugi Shinsaku died of tuberculosis rather than in war, but is nonetheless enshrined in this monument to the war dead. This inconsistent approach to candidates for gōshi inclusion in the shrine’s rolls of souls has been a subject of debate—and a source of friction—right up through the inclusion of the class A war criminals in 1978.

The Shrine’s Postwar Rebirth

Initially Yasukuni Shrine was conceived as a place for the repose of the souls of Japan’s war dead. As the nation went through the first Sino-Japanese War, the Russo-Japanese War, and World War I, though, the nature of the shrine shifted, and it gradually became a place to pacify the spirits of the deceased, and then to honor them publicly. During World War II in particular, Japanese soldiers would head off to battle with promises to one another to “meet again at Yasukuni.” With this, the shrine had become a spiritual touchstone for Japan’s fighting men. In the militarist atmosphere of the day, it was also defined as a place to honor the “glorious spirits” of those who had died for Japan.

Following Japan’s defeat in the war, though, the victors stepped in to change this. On December 15, 1945, the Supreme Commander for Allied Powers issued the so-called Shintō Directive. This established freedom of religion and sought to sweep away vestiges of militarism by abolishing State Shintō, which had brought the native religion under control of the imperial government and made it a tool of state policy. In 1946 the newly passed Religious Corporations Law provided the basis for turning Yasukuni into an autonomous religious corporation with no ties to any state authorities.

Those enshrined in Yasukuni include not just fallen soldiers, but others held to have died in service of the empire: civilians involved in battle zone relief efforts, workers in factories producing war materiel, Japanese citizens believed to have perished in Soviet war camps following their capture in Japan’s continental holdings at the end of World War II, and crew members and evacuees killed when their vessels were sunk. During the postwar era the shrine continued to add the souls of the dead to its rolls, performing gōshi rites to add them to the enshrined deities as new war deaths were discovered. Shrine officials state that a total of nearly 2.5 million souls have been subject to gōshi over the years.

Politics Steps Back In

Yasukuni Shrine attracts considerable attention today when key politicians—notably the prime minister or members of his cabinet—officially visit the shrine to pay their respects to the war dead. In the postwar era, this first took place on October 18, 1951, when Prime Minister Yoshida Shigeru, members of his cabinet, the speaker of the House of Representatives, and the president of the House of Councillors visited en masse to offer prayers at the Shūki Reitaisai, the autumn festival that is one of Yasukuni’s main annual events.

In 1955, however, the government set forth the position that the prime minister and other ministers of state were not allowed to visit the shrine in their official capacity, as this would fall afoul of Article 20, Clause 3, of the Constitution: “The State and its organs shall refrain from religious education or any other religious activity.” The formal view on the official visits by members of the government was that while they could not be definitively described as either constitutional or unconstitutional, there was an undeniable possibility of the latter. For this reason, Japan’s government has claimed a consistent position on the matter, stating that ministers are not to pay their respects at the shrine in an official capacity given the sensitive nature of the facility.

This does not mean that ministers have followed this guideline over the years. There have been numerous visits by members of the cabinet, made in both their official and private capacities.

War Criminals Become an Issue

The nature of Yasukuni Shrine and the debate surrounding it changed considerably in 1978. On October 17, the shrine carried out gōshi procedures for 14 men who had been executed or died during imprisonment for class A war crimes as defined in Article 6 (“There must be eliminated for all time the authority and influence of those who have deceived and misled the people of Japan into embarking on world conquest . . .”) and Article 10 (“. . . stern justice shall be meted out to all war criminals . . .”) of the Potsdam Declaration, which dictated the terms for Japan’s surrender.

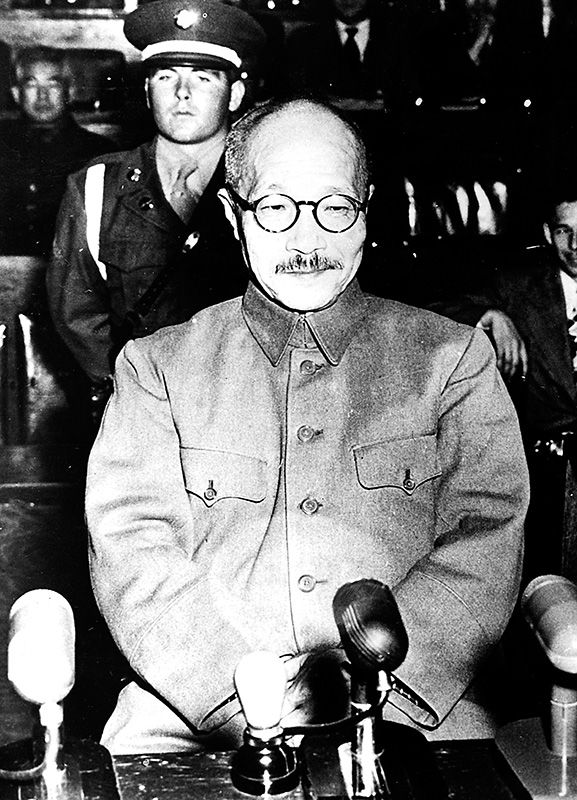

Former Prime Minister Tōjō Hideki at the Tokyo Trials. © Aflo

Former Prime Minister Tōjō Hideki at the Tokyo Trials. © Aflo

The 14 men, convicted of war crimes by the International Military Tribunal for the Far East (the Tokyo Trials), included Tōjō Hideki, general in the Imperial Japanese Army and prime minister for much of World War II; Hirota Kōki, who served as foreign minister and prime minister during the 1930s; and Hiranuma Kiichirō, who was prime minister in 1939, as well as president of the Privy Council. Yasukuni officials described these men as “the Shōwa martyrs” in adding their names to the rolls of enshrined souls. Some of them, including Hirota, were civilians, and none of them had died during wartime, making their inclusion another exceptional case in the history of the shrine.

A complex historical trail leads to the enshrinement of these war criminals. Immediately after the war, there were more than 2 million war dead who had yet to be added to the rolls. Surviving family members pressed for the gōshi rites to be applied to them, too, but it was not until the mid-1950s that the process began for these millions of souls.

In 1959 Yasukuni began formal inclusion of the souls of class B and C war criminals. In the early 1970s, the shrine’s congregational congress agreed that gōshi would be undertaken for the class A war criminals as well. As shrine officials feared the impact of this move on national sentiment, however, it was postponed until 1978—and even then was not formally announced to the public until the following year.

Even the inclusion of this group of 14 souls did not dissuade a number of politicians from paying their respects in person while serving as prime minister. Fukuda Takeo (in office 1976–78) went once, Ōhira Masayoshi (1978–80) three times, Suzuki Zenkō (1980–82) nine times, Nakasone Yasuhiro (1982–87) 10 times, Hashimoto Ryūtarō (1996–98) once, and Koizumi Jun’ichirō (2001–6) six times. Prime Minister Abe Shinzō, currently in office, has made one visit (as of August 2014). Fukuda’s visit took place on the day following the gōshi rites for the class A war criminals, and he stated he was unaware of their inclusion in the shrine’s rolls. Meanwhile, Miyazawa Kiichi (1991–93) never confirmed whether he visited the shrine while in office.

Emperor Shōwa went to Yasukuni eight times after the war ended: in 1945, four times in the 1950s, twice in the 1960s, and for the final time in 1975—the last time an emperor has visited the shrine. The reason there have been no visits since then is generally held to be Emperor Shōwa’s displeasure at the gōshi rites for the class A war criminals.

The Nakasone Years Onward

The year 1985 was one with special historical resonance for Japan, marking the fortieth anniversary of the end of World War II and the eightieth anniversary of its victory in the Russo-Japanese War. Prime Minister Nakasone’s shrine visits accordingly took on additional significance. There had been little opposition to his visits up through the one he made on April 22 that year, but on August 14, the day before he was scheduled to mark the anniversary of Japan’s defeat with prayer at Yasukuni, the Chinese government issued its first formal statement of concern about Japanese leaders’ official visits to the shrine.

Nakasone went through with his visit, praying at the shrine alongside 17 members of his cabinet. This visit became a lightning rod for criticism in part because the prime minister made an offering of flowers paid for with public funds. The backlash was fierce, both in Japan and overseas, and this put an end to prime ministerial visits on August 15 for the next 21 years.

Relations with China and South Korea remained rocky for some time following this, a situation the ruling Liberal Democratic Party sought to assuage by convincing the shrine to undo the gōshi rites for the 14 men in question, or to enshrine them separately. Yasukuni officials rejected these suggestions, stating that once added to the pool of kami, souls could not be un-enshrined.

Regional relations were not improved by the arrival of Koizumi Jun’ichirō in the prime minister’s office in 2001. During the LDP presidential election held in April that year, he had declared his intention to pay his respects at Yasukuni on August 15 no matter what criticism this would draw. He shifted the date of his visit that year to August 13, however, ostensibly to avoid the Chinese and Korean backlash. On that day he released a statement that said in part: “Following a mistaken national policy during a certain period in the past, Japan imposed, through its colonial rule and aggression, immeasurable ravages and suffering particularly to the people of the neighboring countries in Asia. . . . Sincerely facing these deeply regrettable historical facts as they are, here I offer my feelings of profound remorse and sincere mourning to all the victims of the war.”

Prime Minister Koizumi Jun’ichirō visits Yasukuni Shrine on August 15, 2006. © Jiji

Prime Minister Koizumi Jun’ichirō visits Yasukuni Shrine on August 15, 2006. © Jiji

It was in 2006 that Koizumi paid the first August 15 visit to the shrine as prime minister in more than two decades. The Chinese and Korean governments reacted with fury, with Beijing describing his visit as an “act that gravely offends the people in countries victimized by the war of aggression launched by Japanese militarists and undermines the political foundation of China-Japan relations” and Korea’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade expressing the nation’s deep disappointment and anger.

Ambiguity and Openness

Later prime ministers responded to this foreign blowback with a more ambiguous approach to worshiping at Yasukuni. During his first term in office, Abe Shinzō attended the Shunki Reitaisai (annual spring festival) in late April 2007, making an offering of a sacred sakaki tree branch and ¥50,000 of his personal money. When this came to light in the following month, though, he merely stated that he would not comment on whether he had made an offering or not. He was similarly ambiguous when asked about future plans to visit the shrine. Premiers from the Democratic Party of Japan, in power from 2009 to 2012, did not visit Yasukuni at all, although some of their cabinet ministers broke rank to pay their respects on August 15.

Following Abe Shinzō’s election to a second term as prime minister, there was a shift back toward open attendance. Three ministers visited the shrine in April 2013: Aso Tarō, deputy prime minister and finance minister; Furuya Keiji, minister in charge of the North Korean abduction issue; and Shindō Yoshitaka, minister of internal affairs. Then, on April 23, 2013, a total of 168 legislators from the upper and lower houses attended the Shunki Reitaisai—the first time for a group of more than 100 Diet members to visit the shrine at once since October 2005.

Amid intense disapproval from China and Korea, Prime Minister Abe himself publicly attended Yasukuni Shrine on December 26, 2013, one year after he was elected prime minister. However, at the same time he attended the Chinreisha, a shrine dedicated to war dead not enshrined in Yasukuni, including those of all nationalities, and he posted a “Pledge for everlasting peace” on the prime minister and cabinet’s official website in nine languages including Japanese, English, and Chinese.

The Need for a National War Memorial

Is there a way out of this situation for Japan? Removing the class A war criminals from the shrine’s rolls has been suggested as a possible solution to the Yasukuni problem, but the shrine has rejected this, and given the separation of state and religion, the government cannot force its hand in the matter. During the administration of Obuchi Keizō (1998–2000), Chief Cabinet Secretary Nonaka Hiromu proposed changing the shrine’s status from an autonomous religious corporation to a tokushu hōjin, or special public corporation, and then reversing the gōshi of the 14 problematic souls. This plan, too, fell by the wayside.

Another proposal is to construct a secular, national war memorial facility where public figures can pay their respects to the war dead without controversy, but this has not happened either. In 2001, under Prime Minister Koizumi, the Advisory Group to Consider a Memorial Facility for Remembering the Dead and Praying for Peace began discussions, in the following year issuing a report stating that “a national, nonreligious, and permanent facility where the nation as a whole can remember the dead and pray for peace is necessary.” Work never moved forward on such a facility, though. People around the world have places where they can offer their respects to those who died in the service of their country, such as Arlington National Cemetery in the United States. Japan does have the Chidorigafuchi National Cemetery, located near Yasukuni, but this is a place to house the remains of the unknown Japanese war dead, including civilians as well as military and support personnel. The country has no state-managed facility for paying respects to its fallen soldiers.

Yasukuni Outline

• Location Kudankita, Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo. Next to Kitanomaru Park, which lies to the north of the Imperial Palace.

• Managing Body Originally under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of the Interior, the Ministry of War, and the Ministry of the Navy. After World War II, it became an autonomous religious corporation, supported and maintained by major donations and offerings from families and friends of the war dead. The Yasukuni Jinja Sūkei Hōsankai is an organization that helps to support the shrine, currently chaired by former President of the House of Councillors Ōgi Chikage.

• Enshrined kami Those who died supporting the imperial cause before the Meiji Restoration as well as those who were part of or attached to military forces and died for the country in wars or incidents either within Japan or overseas are enshrined as “glorious spirits.” Over 2,466,000 souls have been enshrined.

• Major Festivals The shrine’s most important festivals are the Shunki Reitaisai (spring festival), from April 21 to 23, and the Shūki Reitaisai (autumn festival), from October 17 to 20. The Mitama Matsuri (July 13–16) is a festival that began in the postwar era, based on traditional Obon observances. No special festival is held on August 15 to commemorate the end of World War II, although many visitors choose to attend on this day.

Major Historical Events

1978 Former Prime Minister Tōjō Hideki and other class A war criminals are enshrined.

| 1869 | The newly established Meiji government founds the Tokyo Shōkonsha in the Kudan district of Tokyo to honor those who had fallen in the Boshin War. |

| 1879 | Tokyo Shōkonsha is renamed Yasukuni Shrine. |

| 1945 | Following the end of World War II, the Supreme Commander for Allied Powers abolishes State Shintō. |

| 1946 | The Constitution of Japan is adopted. |

| 1952 | The Allied Occupation ends and Yasukuni Shrine becomes an autonomous religious corporation under the Religious Corporations Law enacted in 1946. |

| 1959 | Chidorigafuchi National Cemetery is completed. |

| 1969 | The Liberal Democratic Party introduces an ultimately unsuccessful bill in the Diet proposing nationalization of Yasukuni Shrine. |

| 1978 | Former Prime Minister Tōjō Hideki and other class A war criminals are enshrined. |

| 1980 | The government announces that attending Yasukuni Shrine in an official capacity may be unconstitutional. |

| 1985 | Prime Minister Nakasone reverses the 1980 decision by visiting Yasukuni Shrine in an official capacity on War Memorial Day (August 15). On August 7, the Asahi Shimbun publishes a special feature on the “Yasukuni issue”; on August 14, the Chinese government issues its first formal statement of concern about Yasukuni visits. |

| 2006 | Koizumi Jun’ichirō becomes the first sitting prime minister for 21 years to attend the shrine in an official capacity. |

Yasukuni’s Enshrined Souls

| Boshin War and Meiji Restoration (1867–69) | 7,751 |

| Invasion of Taiwan (1874) | 1,130 |

| Satsuma Rebellion (1877) | 6,971 |

| Sino-Japanese War (1894–95) | 13,619 |

| Boxer Rebellion (1900) | 1,256 |

| Russo-Japanese War (1904–5) | 88,429 |

| World War I (1914–18) | 4,850 |

| Jinan Incident (1928) | 185 |

| Mukden Incident (1931–37) | 17,176 |

| Sino-Japanese War (1937–41) | 191,250 |

| World War II (incl. Pacific theater and Indochina; 1941–45) | 2,133,915 |

| Total | 2,466,532 |

Note: Conflicts and numbers of souls are as listed in Yasukuni Shrine documents.

Enshrined Class A War Criminals

| Tōjō Hideki | Army general | Prime minister, minister of war | Executed |

| Hirota Kōki | Diplomat | Prime minister, foreign minister | Executed |

| Doihara Kenji | Army general | Mukden Military Intelligence Bureau director | Executed |

| Itagaki Seishirō | Army general | China Expeditionary Army chief of staff | Executed |

| Kimura Heitarō | Army general | Burma Area Army commander in chief | Executed |

| Matsui Iwane | Army general | Central China Area Army commander in chief | Executed |

| Mutō Akira | Army lieutenant general | Ministry of War Military Affairs Bureau director | Executed |

| Hiranuma Kiichirō | Judicial officer | Prime minister, president of the Privy Council | Life sentence |

| Shiratori Toshio | Diplomat | Ambassador to Italy | Life sentence |

| Koiso Kuniaki | Army general | Prime minister, governor-general of Korea | Life sentence |

| Umezu Yoshijirō | Army general | Kwantung Army commander in chief | Life sentence |

| Tōgō Shigenori | Diplomat | Foreign minister, ambassador to Germany, ambassador to Soviet Union | 20 years’ imprisonment |

| Nagano Osami | Navy admiral of the fleet | Minister of the Navy | Died of natural causes before end of trial |

| Matsuoka Yōsuke | Diplomat | Foreign minister | Died of natural causes before end of trial |

Postwar Imperial Visits

Emperor Shōwa made a total of eight postwar visits to Yasukuni Shrine, starting in 1945. He attended for the last time on November 21, 1975, which was the last imperial visit to date; Emperor Akihito has never attended the shrine.

Postwar Visits by Sitting Prime Ministers

April visits are for the Shunki Reitaisai (spring festival) and October visits are for the Shūki Reitaisai (autumn festival).

| Higashikuni Naruhiko | 1 (August 18, 1945) |

| Shidehara Kijūrō | 2 (October 23, 1945; November 20, 1945) |

| Katayama Tetsu | 0 |

| Ashida Hitoshi | 0 |

| Yoshida Shigeru | 5 (October 18, 1951; October 17, 1952; April 23, 1953; October 24, 1953; April 24, 1954) |

| Hatoyama Ichirō | 0 |

| Ishibashi Tanzan | 0 |

| Kishi Nobusuke | 2 (April 25, 1957; October 21, 1958) |

| Ikeda Hayato | 5 (October 18, 1960; June 18, 1961; November 15, 1961; November 4, 1962; September 22, 1963) |

| Satō Eisaku | 11 (April 21, 1965; April 21, 1966; April 22, 1967; April 23, 1968; April 22, 1969; October 18, 1969; April 22, 1970; October 17, 1970; April 22, 1971; October 18, 1971; April 22, 1973) |

| Tanaka Kakuei | 5 (July 8, 1972; April 23, 1973; October 18, 1973; April 23, 1974; October 19, 1974) |

| Miki Takeo | 3 (April 22, 1975; August 15, 1975; October 18, 1976) |

| Fukuda Takeo | 4 (April 21, 1977; April 21, 1978; August 15, 1978; October 18, 1978) |

| Ōhira Masayoshi | 3 (April 21, 1979; October 18, 1979; April 21, 1980) |

| Suzuki Zenkō | 9 (August 15, 1980; October 18, 1980; November 21, 1980; April 21, 1981; August 15, 1981; October 17, 1981; April 21, 1982; August 15, 1982; October 18, 1982) |

| Nakasone Yasuhiro | 10 (April 21, 1983; August 15, 1983; October 18, 1983; January 5, 1984; April 21, 1984; August 15, 1984; October 18, 1984; January 21, 1985; April 22, 1985, August 15, 1985) |

| Takeshita Noboru | 0 |

| Uno Sōsuke | 0 |

| Kaifu Toshiki | 0 |

| Miyazawa Kiichi | (not clear whether he attended or not) |

| Hosokawa Morihiro | 0 |

| Hata Tsutomu | 0 |

| Murayama Tomiichi | 0 |

| Hashimoto Ryūtarō | 1 (July 29, 1996) |

| Obuchi Keizō | 0 |

| Mori Yoshirō | 0 |

| Koizumi Jun'ichirō | 6 (August 13, 2001; April 21, 2002; January 14, 2003; January 1, 2004; October 17, 2005; August 15, 2006) |

| Abe Shinzō (first term) | 0 |

| Fukuda Yasuo | 0 |

| Asō Tarō | 0 |

| Hatoyama Yukio | 0 |

| Kan Naoto | 0 |

| Noda Yoshihiko | 0 |

| Abe Shinzō (second term) | 1 (December 26, 2013) |

Created by Nippon.com based on Yasukuni Shrine records as of March 2014

Yasukuni Shrine Keywords

• Tamagushi An offering consisting of evergreen branches, usually from the sacred sakaki tree, to which folded paper strips (shide) have been attached. Tamagushi are presented to the deities by worshippers and priests at Shintō ceremonies such as weddings and memorial services. Sometimes donations are made in the form of money to pay the shrine to make the offerings.

• Private and Official Visits There are numerous debates surrounding private and official visits to Yasukuni Shrine, and it is difficult to clearly separate the two. The distinction comes under scrutiny in the case of the prime minister, cabinet members, and members of the Diet. For example, when Prime Minister Nakasone made an official visit in 1985, he used public money to donate ordinary flowers rather than a tamagushi to avoid violating the constitutional separation of religion and state. Earlier, Prime Minister Miki had set forth four basic principles that made his visit a private one: he did not use an official car, he donated his own money for a tamagushi, he did not sign his title in the registry, and he was not accompanied by public officials. However, this was his personal statement and not a government position.

• Chidorigafuchi National Cemetery Constructed by the Japanese government in 1959, Chidorigafuchi National Cemetery is located in Sanbanchō, Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo. It houses the remains of over 350,000 unknown soldiers who died overseas during World War II and could not be returned to their families. In October 2013, US Secretary of State John Kerry and Secretary of Defense Chuck Hagel visited the cemetery and offered flowers.

• Yūshūkan A museum within the grounds of Yasukuni Shrine that displays possessions and documents belonging to enshrined soldiers and weapons used during wartime. After opening initially in 1882, it closed its doors in September 1945 before reopening in 1986. The tone of the exhibits and explanations are supportive of the Japanese government’s policies from the Manchurian Incident to the end of World War II.

• Chinreisha A small shrine built south of Yasukuni’s main shrine in 1965. It enshrines the souls of those Japanese who died in wars and disturbances since the last days of the shogunate in the mid-nineteenth century and are not enshrined in Yasukuni Shrine, as well as those of any nationality who have died in wars around the world. When Prime Minister Abe visited Yasukuni’s main shrine in December 2013, he also visited Chinreisha.

(Originally published in Japanese on August 13, 2014. Banner photo shows Yasukuni Shrine. © Jiji)

China Abe Shinzō Nakasone Yasuhiro Koizumi Jun'ichirō South Korea constitution Yasukuni Shrine prime minister class-A war criminals Shintō foreign relations State Shintō Tojo Hideki Emperor Showa Hirohito