Cool for School? The AC Gap in Japanese Classrooms

Society Lifestyle- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

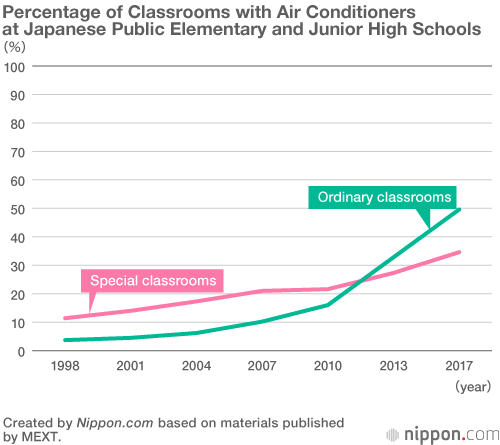

Just under half of classrooms are equipped with air conditioners in Japanese public elementary and junior high schools. A study conducted by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology (MEXT) found that as of April 1, 2017, 193,003 out of a total of 388,776 standard classrooms, or 49.6%, had air conditioning. This is a 16.8% increase over the level in fiscal 2014, when the previous study was conducted, but still around half of standard classrooms place students and teachers at risk of heatstroke.

The installation rate in special classrooms, such as for cooking or music classes, is 41.7%, while the rate is just 1.2% for sports facilities such as gymnasiums and martial arts dōjō.

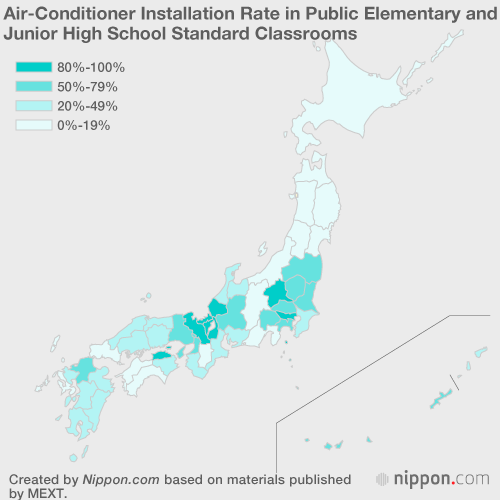

Tokyo has an installation rate of 99.9%, followed closely by Kagawa Prefecture with 97.7%. Other prefectures topping 80% are Fukui (86.5%), Gunma (85.7%), Kyoto (84%), and Shiga (82.8%).

In contrast, 20 prefectures have an installation rate below 20%. At first glance it might seem acceptable that the rate would be lower in the north of the country, but it is not uncommon in that region for temperatures to exceed 30 degrees in the summer. This year, in fact, a temperature of 30 degrees was recorded in the town of Ōzora in Hokkaidō as early as April 30. Moreover, the northern prefectures have a longer winter vacation due to the heavy snowfall there, which is compensated for by a shorter summer vacation. This means that the second semester there starts in late August, when temperatures remain high.

Some prefectures that have a low installation rate despite being prone to high temperatures due to being located in a basin or a southern location included Nara at 7.4%, Ehime at 5.9%, and Nagasaki at 8.6%.

There is high awareness of the issue, as installation of air conditioners at public schools has been the repeated focus of attention at local assemblies and the subject of campaign promises among mayoral candidates.

But the effort to increase installation has been stymied by the tremendous costs involved. MEXT covers one-third of the installation costs through a fund to improve school facilities, but it can still cost several billion yen if a municipality wants to install air conditioners at all of its schools at once. On top of this, there are costs related to electricity usage and maintenance.

On July 24, 2018, Chief Cabinet Secretary Suga Yoshihide noted at a press conference that “Coming up with countermeasures for this brutal heat is a pressing issue as we seek to protect the safety and health of young children and older students,” stating that the government was considering providing financial assistance for elementary and junior high schools seeking to install air conditioning. “The government is prepared to ensure that this equipment is in place in time for this season next year,” he continued.

In July 2017, local governments in Aichi Prefecture measured the temperature in public elementary and junior high classrooms over a two-week period and found that the highest temperatures recorded were 35.9 degrees at a school located in an urban area and 32.4 degrees at a school in a mountainous area. Japanese adults should try to imagine the sort of problems that such heat can cause for children. Perhaps they can best do so by considering how much productivity in an office would drop when the temperature exceeds 30 degrees or the sort of health issues that can arise from such conditions.

(Translated from Japanese. Banner photo: © Pixta.)