Tatami

Culture- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

The Structure of Tatami

Japan’s traditional tatami flooring appeals to the senses. Muted in color and springy but firm underfoot, it gives off a faint straw-like aroma. The geometric arrangement of rectangular mats also adds shape to a room. Although the nation’s homes are now largely equipped with wooden flooring, they often have at least one washitsu or Japanese-style room with tatami. It is also used in rooms for performing the tea ceremony and other traditional arts. To avoid damage to the mats, it is customary to take shoes or slippers off when entering a tatami room.

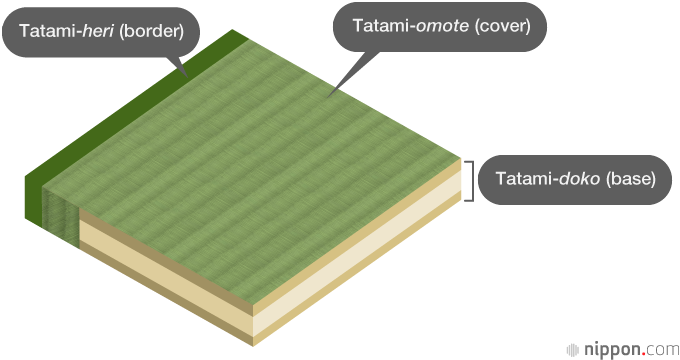

Tatami consists of three main parts. The tatami-doko (base) is protected by the tatami-omote (cover), and the tatami-heri (border) is sewn on around the edge of each mat. The base is around five centimeters thick and was traditionally made of compressed layers of rice straw. In recent years, however, reduced supply and concerns with mite and mold infestation have led to the widespread use of polystyrene foam or compressed wood-chip boards.

The moderate elasticity of tatami makes it pleasant to stand or sit on. The flooring also helps to regulate humidity through absorption and acts as a basic layer of insulation.

A Local Invention

The size of individual tatami mats varies a little by region, but they are usually shaped like a 2:1 rectangle with a standard size of around 91 cm x 182 cm. The area of apartments is often given in terms of the number of mats—whether the rooms are washitsu or not—but estate agents use a slightly smaller size when doing so. Japanese-style rooms generally range in proportions from smaller 3- and 4.5-mat sizes to more spacious 6- and 8-mat spaces.

While Japan has a long tradition of borrowing from neighboring countries, tatami is believed to be a local invention. The oldest surviving tatami is preserved at the Tōdaiji temple in Nara and dates back to the middle of the eighth century.

Tatami first appeared in aristocratic residences during the Heian period (794–1185) as a form of covering for small areas of floor, where it served as cushions or bedding. From the late twelfth century onward it grew increasingly common and came to be applied to the whole of the room. Ordinary citizens began to use it from the mid-Edo period (1603–1868), and it finally became standard in farming villages from the Meiji period (1868–1912).

Tatami Today

Japanese lifestyles rapidly Westernized after World War II, but tatami washitsu have remained important features of Japanese residences. Since around the 1990s, however, homes with wooden floors and no tatami have grown in popularity.

National demand for tatami-omote covers dropped by two-thirds between 1993 and 2012, according to a survey conducted by a group promoting production and sales in Japan’s leading igusa-producing area Kumamoto Prefecture. Overall demand was for 45 million covers in 1993, but this fell to 14.9 million in 2012.

A futon laid out on tatami acts as a bed. When not in use, the futon can be stored in a closet.

A futon laid out on tatami acts as a bed. When not in use, the futon can be stored in a closet.

Even if it is no longer central, there is still a space for tatami in many Japanese homes, whether in traditional or new forms. Some tatami now available is designed to be laid on top of wooden floors, while colorful covers using materials other than igusa add a fresh touch.

As a durable natural material, traditional tatami is biodegradable and environmentally friendly. It suits those who like a plain, uncomplicated life, as simply laying down zabuton cushions and a futon serves as seating and a bed. Visitors to Japan can try the tatami lifestyle for themselves by staying at ryokan lodgings.