“Life After Manzanar”: Examining the Legacy of Japanese American Incarceration

Culture- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

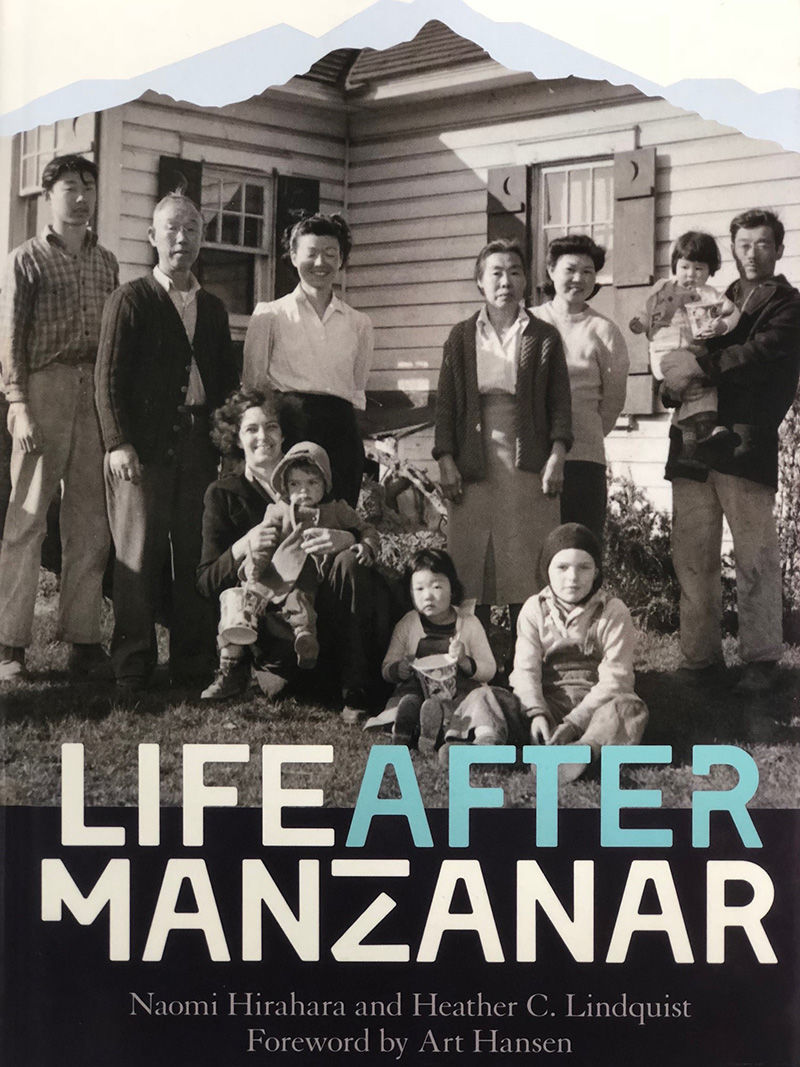

Award-winning writer Naomi Hirahara and exhibit planner Heather C. Lindquist, in their recently published Life After Manzanar, offer a compelling account of the lives of Japanese and Japanese Americans incarcerated during World War II. Relying on archival accounts and historic photos, the pair skillfully weave the personal narratives of prisoners into a cohesive narrative stretching from the postwar years through to the reparations movement in the 1980s and into the present.

An Unjust Imprisonment

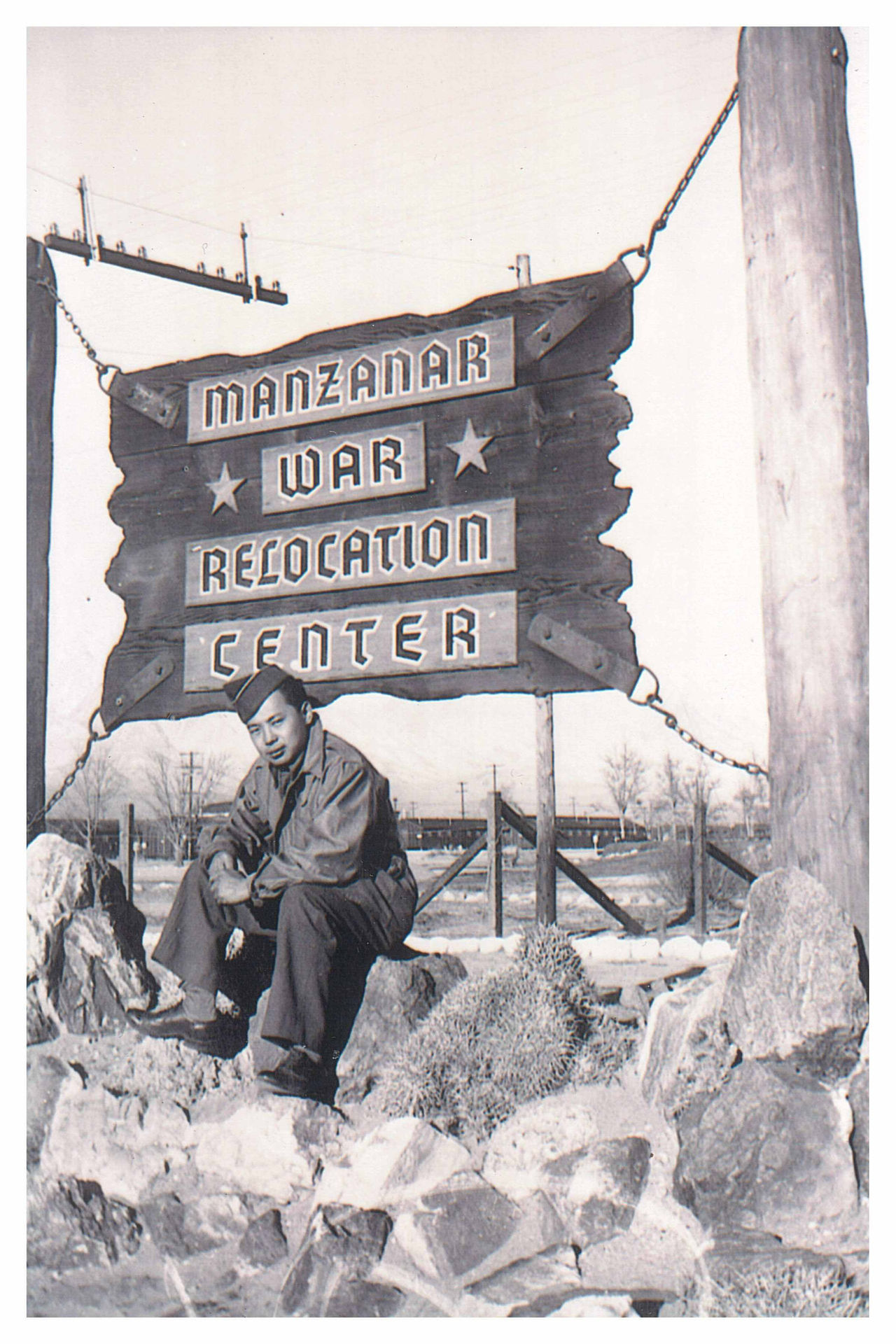

Private Ben Hatanaka, on furlough from the US Army, sits under the entrance sign at Manzanar while visiting family members imprisoned there. (Courtesy of California State University, Sacramento Library, and Jill Hatanaka)

Private Ben Hatanaka, on furlough from the US Army, sits under the entrance sign at Manzanar while visiting family members imprisoned there. (Courtesy of California State University, Sacramento Library, and Jill Hatanaka)

Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, sparked fears of a national security crisis in the United States. In response, President Franklin D. Roosevelt on February 19, 1942, signed Executive Order 9066, leading to the internment of some 120,000 people of Japanese ancestry in concentration camps around the country.

People of Japanese descent, two-thirds of whom where native-born Americans, were uprooted from their homes, jobs, and communities and incarcerated in what were called war relocation centers but were in effect concentration camps, with barbed-wire fences and armed guards. The largest of these camps was Manzanar, California, about 340 kilometers north of Los Angeles, which at its peak housed over 10,000 internees.

Iconic works like Farewell to Manzanar by James D. Houston and Jeanne Wakatsuki Houston document the harsh environment and cramped living conditions, along with the heavy emotional and economic toll the imprisonment took on internees. In Life After Manzanar, Hirahara and Lindquist continue the narrative, turning their attention to the struggles of the Japanese American community as people tried to reintegrate into society in the years after the camps were shuttered.

Rebuilding, Healing, and Remembering

The book begins on November 21, 1945, as the last 49 people prepare to leave the Manzanar War Relocation Center. From there it gently guides readers along the divergent roads incarcerees followed in rebuilding their lives.

In the first two chapters, the authors recount stirring stories of triumph and tragedy to portray the gritty reality internees faced in the immediate postwar years. Far from blending seamlessly back into society, people of Japanese ancestry often struggled to get back on their feet. Work and adequate housing were in short supply, and people struggled against the impact of fractured communities, lost livelihoods, and barefaced racism.

Incarcerated in Manzanar as young children, Natalie Hayashida, Jane Kitamoto, and Susan Hayashida (left to right) proudly sport Brownie uniforms in the early 1950s. (Courtesy of Densho and the Hayashida Family Collection)

Incarcerated in Manzanar as young children, Natalie Hayashida, Jane Kitamoto, and Susan Hayashida (left to right) proudly sport Brownie uniforms in the early 1950s. (Courtesy of Densho and the Hayashida Family Collection)

The authors weave a poignant narrative tapestry, including the story of Buddhist minister Shinjo Nagatomi, a caretaker of the physical and spiritual needs of prisoners and one of the last incarcerees to leave Manzanar, and aspiring medical student Chico Sakaguchi, who died tragically while being treated for asthma that family members said was due to the camp’s dusty conditions. There are also disturbing tales like that of Joe Kurihara, a World War I veteran who felt betrayed by his country at being treated as a criminal despite his service, leading him to renounce his US citizenship and live the remainder of his life in Japan.

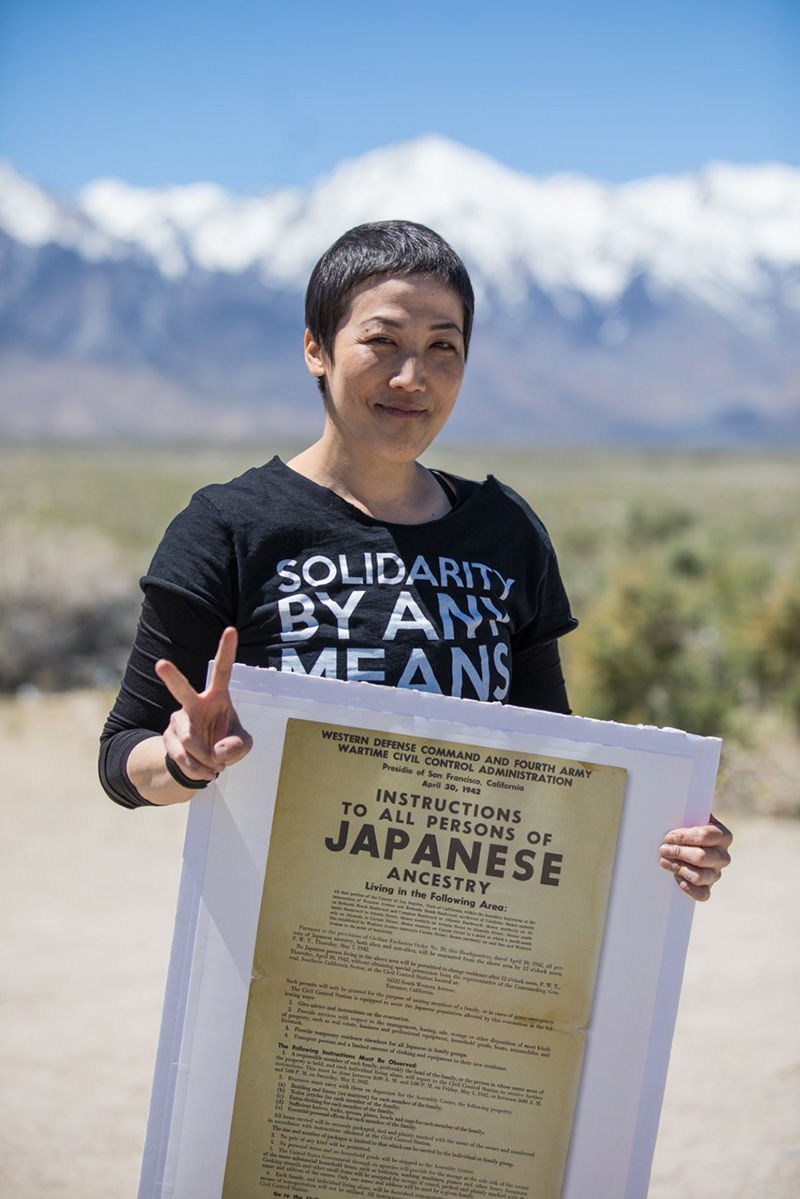

In the second half of the work Hirahara and Lindquist turn their attention to the struggles of the Japanese-American community in later decades to overturn discriminatory legislation targeting Japanese immigrants and the evolution of the redress and reparations movement that culminated in the 1988 Civil Liberties Act. It then goes on to detail the efforts and ongoing challenges faced in passing the legacy of Manzanar on to successive generations.

Hundreds of people—both Japanese citizens and Americans who had renounced US citizenship—embark for Japan from Seattle in 1945. (Courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration)

Hundreds of people—both Japanese citizens and Americans who had renounced US citizenship—embark for Japan from Seattle in 1945. (Courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration)

Relocating Communities

Of particular note is the light that Life After Manzanar sheds on the systematic resettlement of Japanese Americans, a topic that has received comparatively little scholarly attention. Starting in 1942, tens of thousands of people were methodically relocated from West Coast communities to interior cities like Chicago and Denver, and even as far as New York on the East Coast. The book details the ways private and government organizations helped orchestrate the relocation under schooling, employment, and other pretexts and illustrates the long-lasting repercussions this systematic dislocation had on families, friends, and communities.

Hirahara and Lindquist have filled the book with historic photos, helping put faces to the stirring stories it recounts. With Life After Manzanar, the authors have created an instructive and moving work documenting the resilience of the Japanese-American community. At the same time, they provide a powerful reminder of the consequences of remaining silent in the face of policies driven by racism and xenophobia.

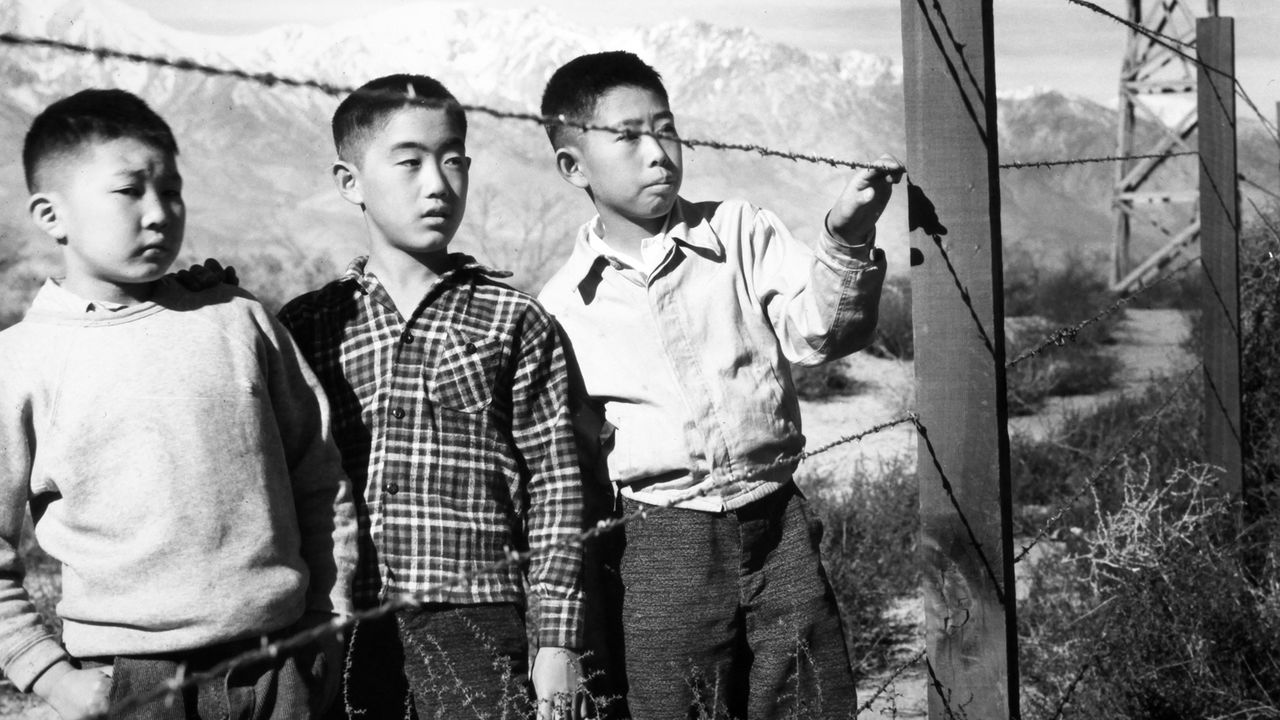

Left to Right: Bob Takamoto, Bruce Sansui, and Mas Ooka revisit Manzanar, July 2016. (© Toyo Miyatake Studio)

Left to Right: Bob Takamoto, Bruce Sansui, and Mas Ooka revisit Manzanar, July 2016. (© Toyo Miyatake Studio)

Traci Kato-Kiriyama, daughter of a Manzanar incarceree, at the forty-eighth annual Manzanar Pilgrimage in April 2017, which commemorated the seventy-fifth anniversary of the signing of EO 9066. (© Matt Givot)

Traci Kato-Kiriyama, daughter of a Manzanar incarceree, at the forty-eighth annual Manzanar Pilgrimage in April 2017, which commemorated the seventy-fifth anniversary of the signing of EO 9066. (© Matt Givot)

Life After Manzanar, written by Naomi Hirahara and Heather C. Lindquist, was published by Heyday Books in April 2018.

(Originally published in English. Banner photo: Left to Right: Bob Takamoto, Bruce Sansui, and Mas Ooka look out from behind Manzanar’s barbed wire fence in 1944. © Toyo Miyatake Studio.)

World War II literature Nippon.com Book Reviews United States