Tanabata in Times Past: “Tanabata Festival in the Flourishing City”

Guideto Japan

- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

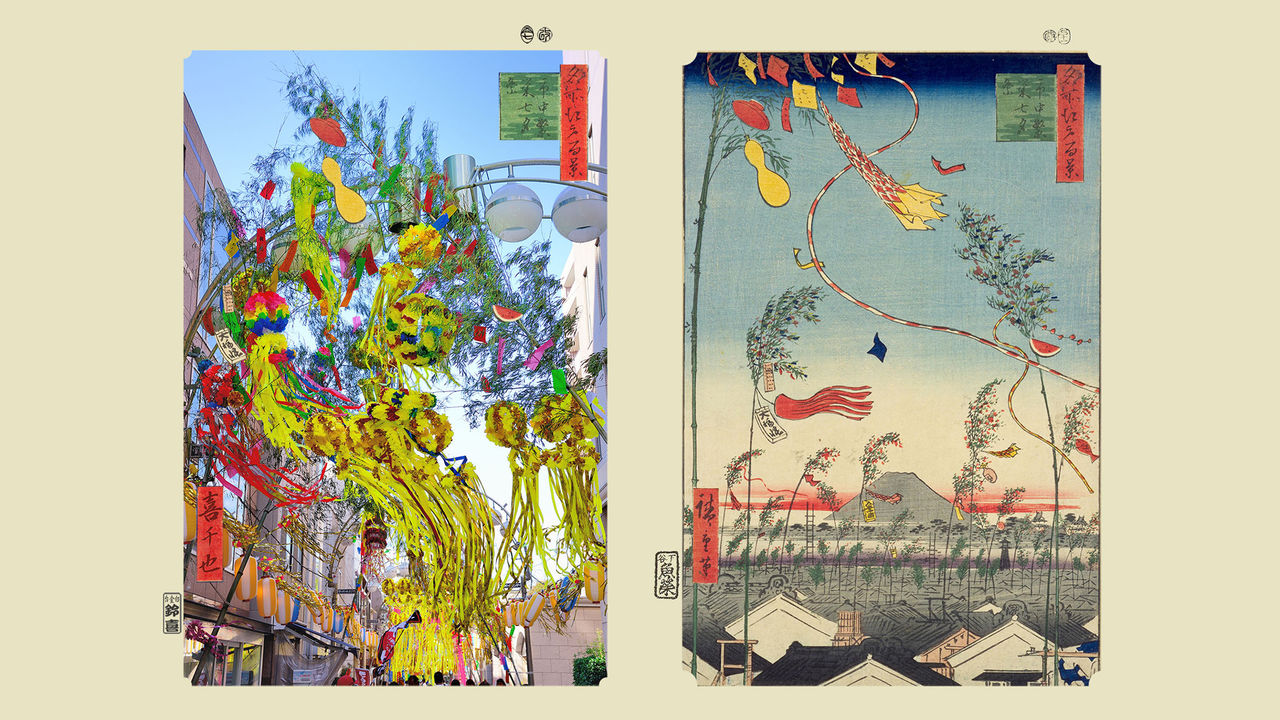

One Hundred Famous Views of Edo by Kichiya, the Ukiyo Photographer: Today’s Tokyo Through Hiroshige’s Eyes

Meisho Edo hyakkei, known in the West as One Hundred Famous Views of Edo, was one of ukiyo-e artist Utagawa Hiroshige’s most celebrated works, influencing even Western artists like Van Gogh and Monet. Drawn in Hiroshige’s final years and published from 1856 to 1861, the series depicted the sights of Edo (as Tokyo was then known) through the changing seasons. Audiences around the world admired Hiroshige’s inventive use of bold compositions, bird’s-eye-view perspectives, and vivid colors. A century and a half later, “ukiyo photographer” Kichiya has set himself the task of recreating each of these views with a photograph taken in the same place, at the same time of year, from the same angle. Join us in this new series at Nippon.com on a tour of these “famous views” in Edo and modern-day Tokyo, guided by Kichiya’s artistry and his knowledge of old maps and life in Edo.

Tanabata Decorations Proclaim Edo’s Prosperity to Blue Summer Skies

“Tanabata Festival in the Flourishing City” is the only print in Hiroshige’s Hundred Famous Views not to specify a place name in its title, although many experts believe that it depicts the view from Hiroshige’s home in Ogachō.

Tanabata, also known as the Star Festival, is celebrated on the seventh day of the seventh month, which is said to be the one night of the year that the lovers Hikoboshi the cowherd (the star Altair) and Orihime the weaver (Vega) are reunited across the river of heaven (the Milky Way). Under the old lunar calendar, on the seventh night of any month the moon was always in its first quarter phase, and this silvery half-circle was said to be the boat that reunited the two lovers. Realizing this is enough to make you reconsider the wisdom of simply holding the festival on July 7 of the Gregorian calendar every year, when the moon could be in any phase at all.

I took this shot in 2016 at the Asagaya Pearl Center’s Tanabata Matsuri. The celebrations here run until the equivalent of July 7 on the lunar calendar, which in that year meant August 9. The Pearl Center is basically a covered arcade, but venturing out into the adjoining commercial district I found some tanabata decorations waving against the blue sky, just like in Hiroshige’s original. Mount Fuji was sadly absent from the tableau, but the humid summer atmosphere was a perfect match in every other way.

Background Information about Tanabata

A Chinese tradition that arrived in Japan during the Nara period (710–94). Originally celebrated on the seventh day of the seventh lunar month, or the night before. When Japan adopted the Gregorian calendar in 1873, tanabata came to be observed on July 7, roughly a month earlier in terms of the cycle of seasons. What’s more, as July 7 falls during Japan’s rainy season, the cosmic drama is often obscured by clouds.

There are some places that still observe the original timing of the festival, including the Asagaya Tanabata Matsuri, where I took my photograph, and the Sendai Tanabata Matsuri, one of Japan’s largest. But the July 7 date is used by major Tokyo temples and shrines like Kanda Shrine, Zōjōji temple, and Tokyo Daijingū, so checking in advance is a good idea for would-be sightseers.

tourism Tokyo ukiyo-e One Hundred Famous Views of Edo by Kichiya Kantō