The Maizuru Repatriation Memorial Museum: Sharing the Memory of Siberian Internment

Guideto Japan

History Society- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Maizuru, Gateway Back to the Homeland

Maizuru in Kyoto Prefecture was one of 18 ports in Japan designated to receive the 6.6 million Japanese military personnel and civilians stranded in overseas territories after the end of World War II. Most had been repatriated by 1947; after 1950, Maizuru was the only such port remaining until repatriations finally ended in 1958.

The guided tour to the Maizuru Memorial Repatriation Museum begins with an explanation: “This museum was built to help us remember that for Japanese troops held in forced labor camps in Siberia, Maizuru was the gateway to their postwar experience.” Indeed, Maizuru, a northern Kyoto Prefecture city on the Sea of Japan, was the port of arrival for 660,000 repatriates who landed there from 1945 onward.

In his radio broadcast to the nation on August 15, 1945, Emperor Hirohito (r. 1926–89; posthumously styled Shōwa) announced acceptance of the Potsdam Declaration and the end of the war. While this year has seen extensive media coverage of the eightieth anniversary of the war’s end, for Japanese internees returning from Siberia, the postwar era began only when they had arrived back to Japan, in some cases more than a decade after the formal end of the war.

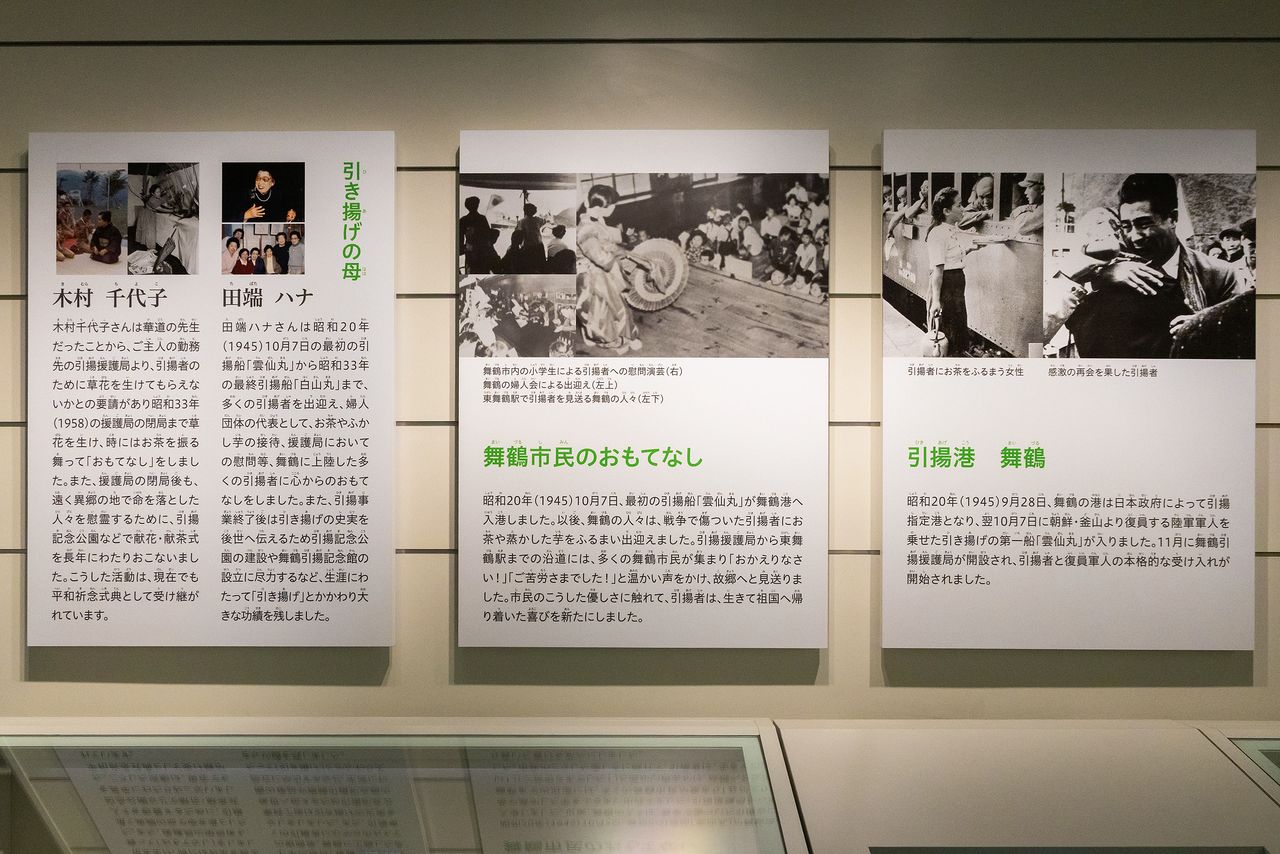

For 13 long years, the inhabitants of Maizuru warmly welcomed each arriving repatriation ship and offered tea and steamed sweet potatoes to the passengers as they disembarked. Since repatriation ships continued to arrive in Maizuru for more than a decade after the war’s end, in a real sense, the city’s “postwar” era also did not begin until the last of the internees had made their way back to Japanese shores.

The Maizuru Repatriation Memorial Museum, refurbished in 2015. (© Nippon.com)

The photo at the entrance to the permanent exhibit, showing crowds waiting on the pier for the repatriated citizens, packs an emotional punch. (© Nippon.com)

A photo panel displays the welcoming gestures by the citizens of Maizuru, who served tea and provided light entertainment for returnees. (© Nippon.com)

Beginning in the 1980s, as those who had been interned in Siberia grew old, some expressed the desire for a memorial in Maizuru to symbolize their homecoming. They also believed such a memorial would help attract visitors to Maizuru as a way of giving thanks to the city that had welcomed them back. The former internees and Maizuru residents raised donations totaling ¥74 million, Kyoto Prefecture granted a subsidy of ¥20 million, and the city spent ¥240 million to erect a memorial museum, which opened in 1988. Over 16,000 items were donated, of which around 1,000 are on permanent display today.

Spoons and chopsticks crafted by the detainees. Painstakingly made, they helped take detainees’ minds off their meager food rations. (© Nippon.com)

The Maizuru Naval Station

Maizuru consists of two areas: Nishi-Maizuru, to the west, which prospered as a castle town under the Tango Tanabe clan, and Higashi-Maizuru, to the east, which developed as a naval station for the Imperial Japanese Navy.

There were already naval stations at Yokosuka, Kure, and Sasebo (in the prefectures of Kanagawa, Hiroshima, and Nagasaki, respectively); the naval station at Maizuru was the last to open, in 1901. The only one situated on the Sea of Japan, it was developed to counter rising tensions with Imperial Russia. When the Russo-Japanese War (1904–5) broke out, Maizuru played a major role in that conflict, as had been expected. Because of its location, the port was designated to receive many of the Siberian detainees. Of the 660,000 repatriates who landed there after the war, 460,000 came from Siberia.

The view of Maizuru Bay from Mount Gorōgatake. On the Nishi-Maizuru side, the opening to the bay is narrow. Higashi-Maizuru, further inside the bay, commands a key position. (© Nippon.com)

Several models of repatriation ships are on display. Over a 13-year period, these ships docked at Maizuru a total of 346 times. (© Nippon.com)

Internees in Siberia were mostly Japanese soldiers in Manchuria, today’s northeastern China, and Sakhalin who had laid down their arms. In the immediate aftermath of the war, they were herded aboard transport trains to shouts of “You’re going home” or “You’re going back!” in Russian; instead, they were transported to forced labor camps in Siberia, in Russia’s far northeast.

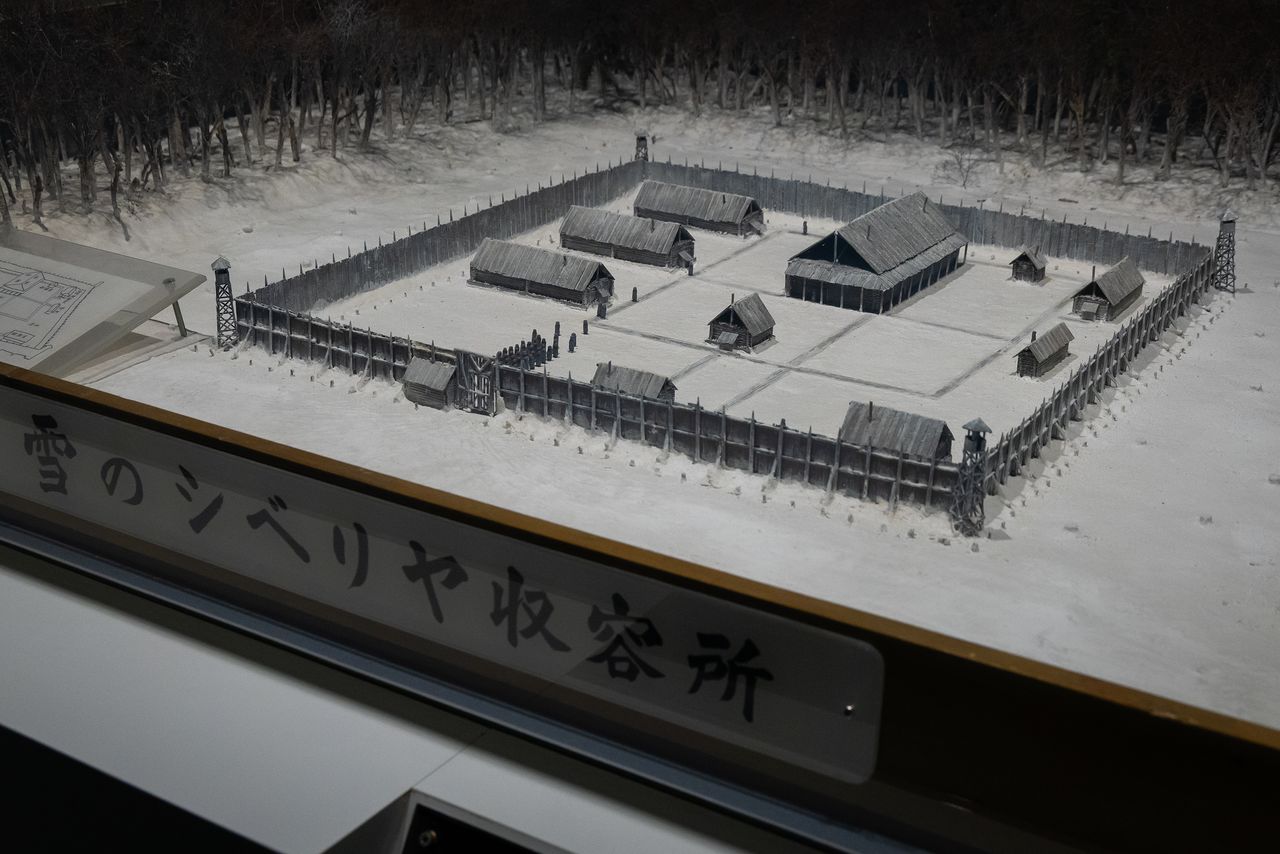

There, they were put to work felling trees, working in coal mines, and building railroads, to fulfill the Soviet Union’s aim of developing Siberia. Winter temperatures often plunged to under minus 30° Celsius, but even so, they were often forced to work outdoors for long hours every day.

A model of a labor camp, with guard towers at the four corners. Some detainees, unable to withstand the harsh conditions, intentionally approached the towers so as to be shot to death. (© Nippon.com)

At many of the labor camps, twice-daily meals consisted of one slice of rye bread and thin soup containing bits of dried vegetables, if anything at all. Hunger was a constant torment; fights often erupted over the size of the bread that had been distributed. There were around 60,000 deaths, a tenth of the 600,000 detained, caused by starvation or unsanitary conditions.

A meal scene at a labor camp. To prevent disputes, bread was cut into equal portions after being weighed on a handmade scale. (© Nippon.com)

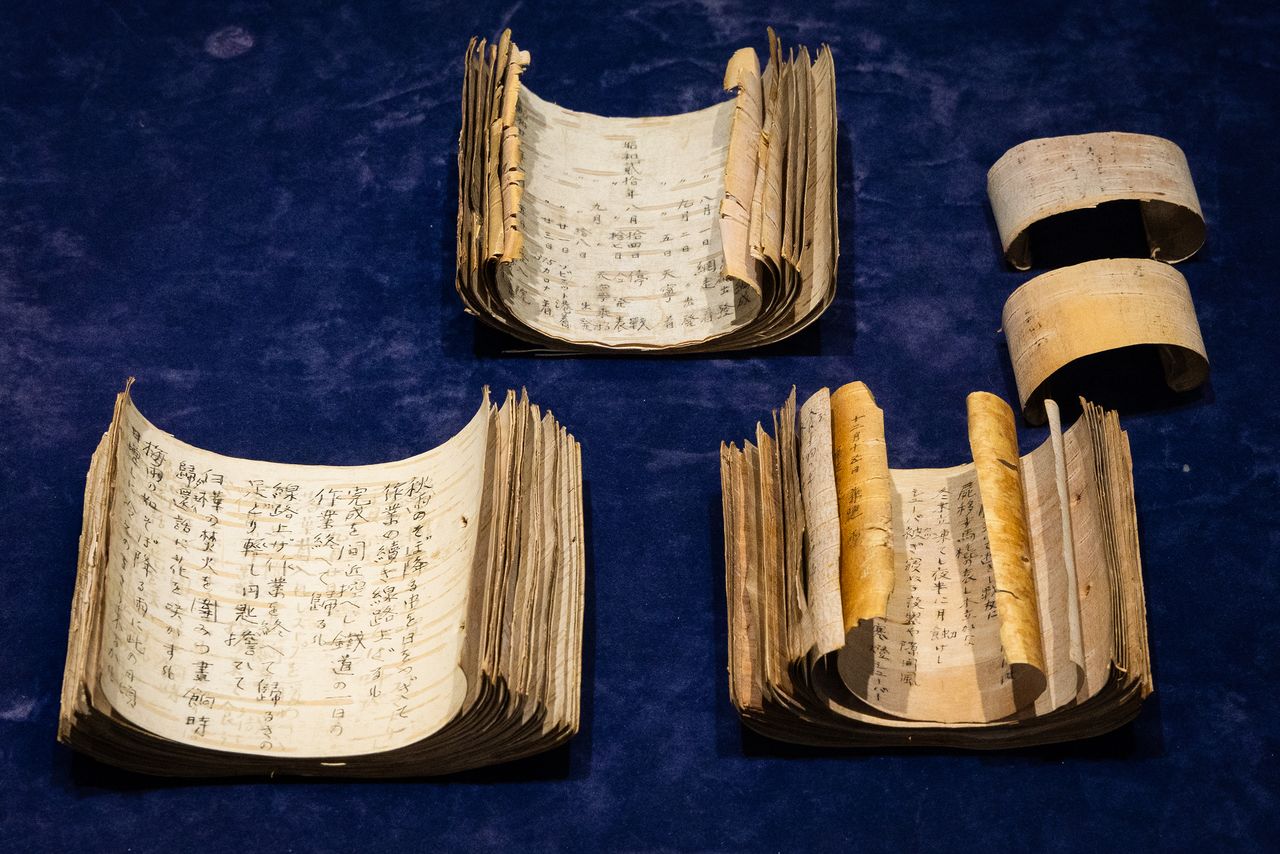

Clinging to Normality

In 2015, 570 of the artifacts held by the museum were inscribed in UNESCO’s Memory of the World International Register. These include precious historical records such as the Shirakaba nisshi (White Birch Diaries), expressing the internees’ longing for home. These were brought back from Siberia by Seno Shū, who was repatriated via Maizuru in 1947. The Shirakaba nisshi contain 200 haiku and tanka poems, written on 36 pieces of birchbark with implements fashioned from tin cans using ink made from a mixture of soot and water.

The Shirakaba nisshi exhibit. (© Nippon.com)

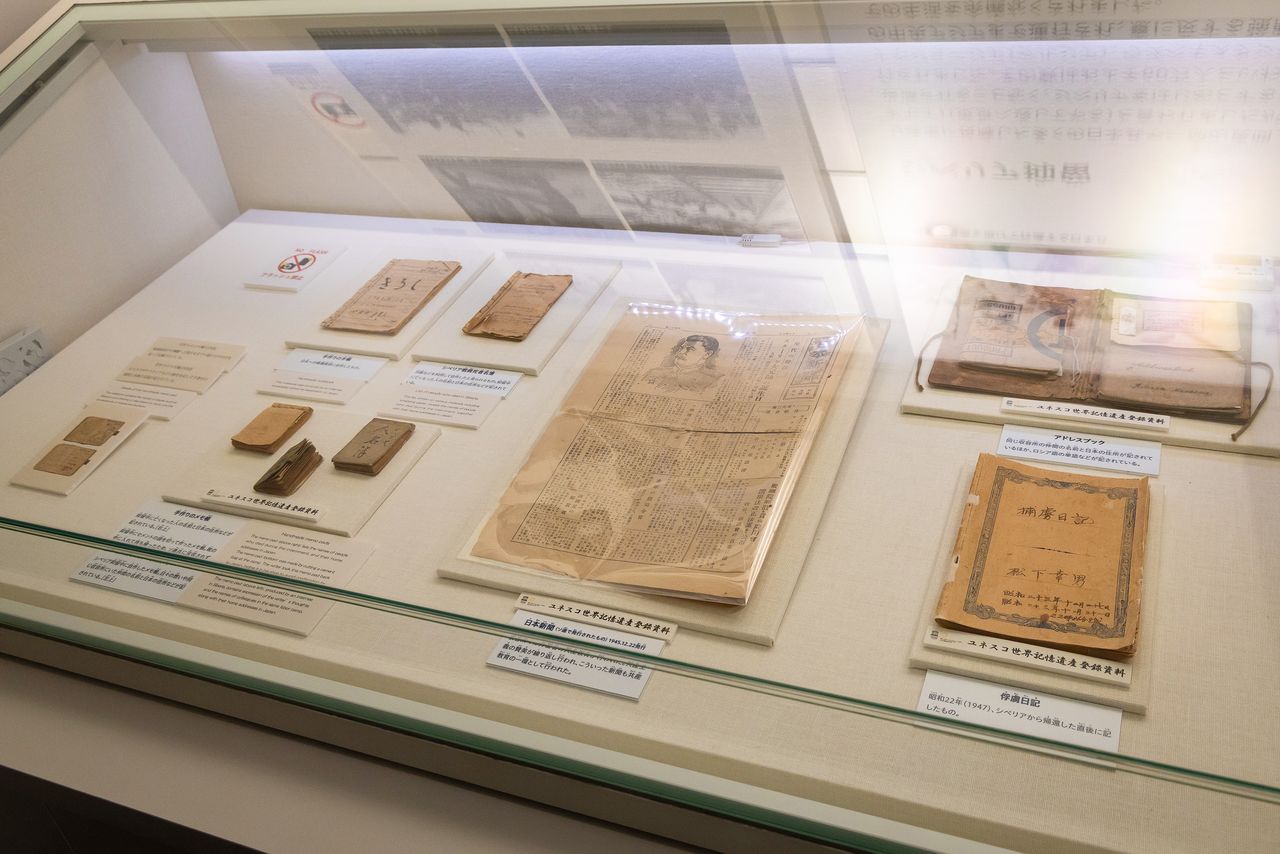

At the labor camps, anyone taking notes or keeping a diary would be suspected of espionage; materials were promptly confiscated. Fearful that information about postwar conditions in the Soviet Union could leak out, Soviet troops would take any records they found when detainees boarded repatriation ships, as did Allied occupation forces when the men disembarked at Maizuru.

But the Shirakaba nisshi, written on 9-by-12-centimeter birchbark sheets the size of a man’s palm, could easily be rolled up and concealed. Miraculously, they made it back to Japan, a potent record of the senselessness and tragedy of war.

Improvised writing implements were used to record the detainees’ thoughts. The writing on the bark remains sharp even 80 years later. (© Nippon.com)

Other items owned and displayed by the museum include lists of detainees’ addresses, letters to their families, and other articles. Writing allowed them to pour their hearts out and hold out in the hope that they would one day see their homeland again.

The prisoners also devised amusements to keep their minds off their daily trials. For example, they played mahjong, using expertly crafted tiles. Many survivors no doubt found comfort in these and other small diversions.

Lists of names and other information on those who died in the labor camps form part of the documents in the Memory of the World International Register. (© Nippon.com)

Wooden mahjong tiles were crafted to fit perfectly in their boxes. (© Nippon.com)

Keeping the Memory Alive

When it first opened, the Maizuru Repatriation Memorial Museum attracted over 200,000 visitors yearly. Initially, they were labor camp survivors’ groups and their families. This helped give a boost to Maizuru, a small city with a population of 80,000. But as memories of the war faded, visitor numbers declined, dropping below 100,000 a year in 2010. City authorities led a movement to place the museum’s materials on the Memory of the World International Register, giving Maizuru a much-needed shot in the arm and renewing recognition of the role it had played as a repatriation port.

Many visitors make their way to the reconstructed Taira Repatriation Pier. (© Nippon.com)

Those who remember the war are very old now, and the task now is to pass on their memories to succeeding generations. Maizuru instituted a storytelling tutorial in 2004, currently operated by the nonprofit Maizuru Repatriation Storytelling Association. Its members are participants who have completed the course, two of whom are always on duty as storytellers at the museum.

Other attractions developed in the city in the past few years include the Maizuru World Brick Museum, a collection of storehouses used when Maizuru was a home port for the Imperial Japanese Navy, and a sightseeing boat that tours sights associated with the area’s history as a navy port. A visit to the city—a poignant reminder of the horrors of war and how we must all continue to strive for peace—is always worthwhile, but perhaps especially pertinent in 2025, the eightieth anniversary of the war’s end.

The Maizuru World Brick Museum houses cafés, a museum shop, and a boarding pier for sightseeing tour boats. (© Nippon.com)

Aegis warships photographed from a sightseeing tour boat. Maizuru is today Japan’s only naval base serving as a port for both the Maritime Self-Defense Force and the Japan Coast Guard. (© Nippon.com)

Maizuru Repatriation Memorial Museum

- Location: 1584 Azataira, Maizuru, Kyoto Prefecture

- Hours: 9:00 am to 5:00 pm (Entrance allowed until 4:30 pm.)

- Closed: Wednesdays (or the following day, if Wednesday falls on a public holiday), New Year’s holidays (Dec. 29–Jan. 1)

- Fees: ¥400 (adults), ¥150 (students)

(Originally published in Japanese. Reporting, text, and photos by Nippon.com. Banner photo: An experience room replicating life in a Soviet internment camp. © Nippon.com.)