The Creative World of Ōsaka Hiromichi, Living National Treasure (Photos)

Culture- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

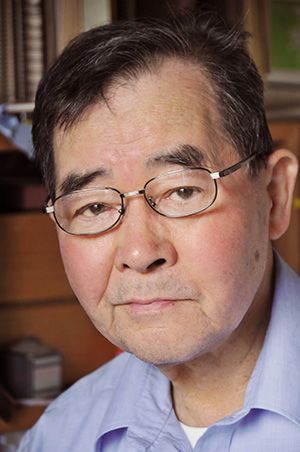

Ōsaka Hiromichi

Born in 1937. After graduating from the fine arts department of Tokyo Gakugei University, worked as a junior high school art teacher. In 1980, he was commissioned by the Imperial Household Agency to recreate several treasures from the collection of the Shōsō-in treasure house at the Tōdai-ji temple in Nara. In 1984, he retired from teaching to concentrate on his craft on a full-time basis. He has won numerous awards and decorations for his work, culminating in his recognition as a Living National Treasure in 1997.

Woodworking that Transcends Time and Space

The living national treasures embody Japan’s rich traditions in the arts and crafts. Officially certified as “preservers of important intangible cultural properties,” these elite artisans possess techniques and skills of exceptional historic or artistic value in a performing art or traditional craft.

Ōsaka Hiromichi, recognized as a Living National Treasure for his woodwork in 1997, honed his skills by creating replicas of historic objects from the Shōsō-in treasure house in Nara. Dating back to the eighth century, the wooden treasure house contains some 9,000 cultural artifacts, including Buddhist ceremonial objects, weapons, ornaments, documents, and scrolls. The treasures include objects from as far afield as Rome and Persia that reached Japan via the Silk Road. The influence of European and West Asian art can be clearly discerned in many of the pieces that Ōsaka was hired to recreate.

Seven Years to Replicate Shōsō-in Treasures

When Ōsaka was commissioned to replicate the Shōsō-in treasures, his first step was to locate the materials he needed. He used his life savings to acquire the special materials and woods he needed to create authentic replicas of these ancient treasures. Ōsaka spent five years researching the tools and materials that the original artisans would have used and tracking down modern equivalents. His first project, a replica of a rosewood box from the Nara period (710-94), took seven years to complete.

Ōsaka specializes in a style of carving known as mokuga (literally “wood picture”), in which delicate patterns are inlaid into wooden objects using ivory, horn, and different types of wood and metal to create complex decorative effects on the surface of the wood. Ōsaka’s rosewood box featured remarkably intricate geometric patterns, in which 30 wafer-thin layers of different materials were used to create delicate decorative motifs just 1 cm wide. Ōsaka succeeded in reviving the techniques used by woodworkers in ancient times.

Painstaking Approach to Beauty

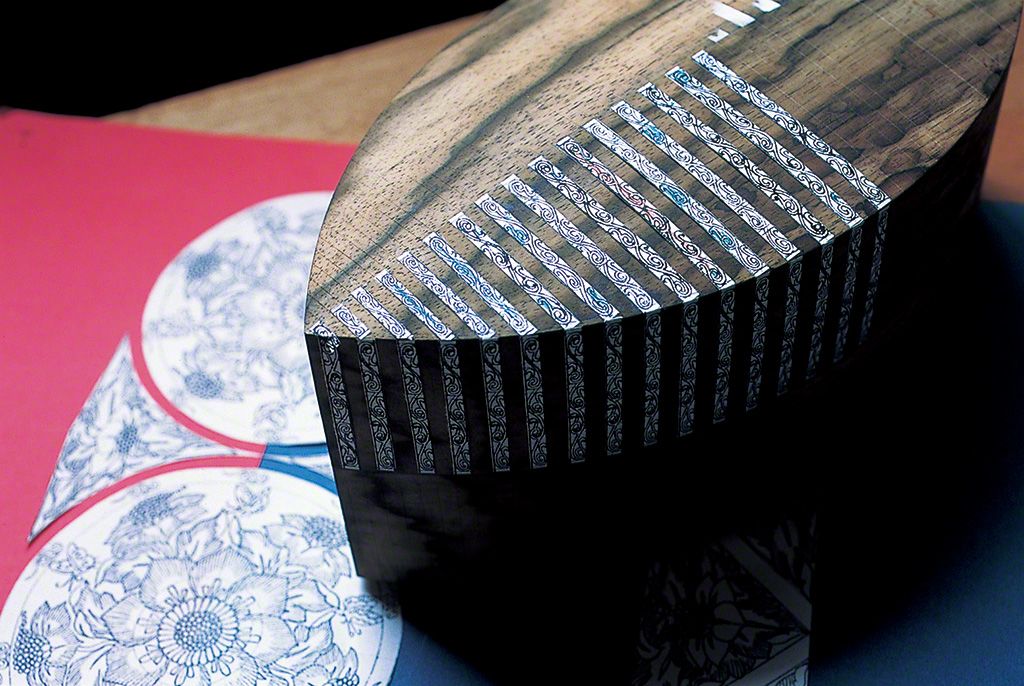

Ōsaka discovered that artisans in the Nara period had used tin inlays to create the patterns on some of the rosewood boxes he was replicating. This inspired him to come up with a distinctive technique. This involves carving a latticework of fine, filigree-like lacing into narrow strips of wood with a coping saw (itonoko) and inlaying thin layers of tin or other material into this lacing. The charming combination of intricate metal tracings and the beautiful surface of the black persimmon wood, tinged with red sappanwood dye, is one of the chief pleasures of Ōsaka’s work.

Ōsaka takes a painstaking approach to making his beautiful objects, creating them at the rate of just two per year. This slide show introduces some of Ōsaka’s masterpieces—works that transcend the framework of traditional Japanese crafts and exert a universal appeal.

The Creative World of Ōsaka Hiromichi, Living National Treasure

Box for writing brush with inlaid scrolling floral design (1994). Tin inlay on black persimmon wood.

Lotus-petal shaped covered container with an inlaid lattice of arabesque-style patterns (1999). Black persimmon wood inlaid with tin. Opening the lid reveals a vibrant world of gold leaf.

Container with an inlaid hōsōge floral design (2002). Tin inlaid on a surface of black persimmon wood. Hōsōge is a type of arabesque that was popular during the Nara (710– 794) and Heian (794–1185) periods.

Incense box inalid with raden and tin (2010). Tin and various shells inlaid on a surface of black persimmon wood. The piece has a beguiling luster, which changes subtly depending on the viewer’s perspective.

Ōsaka Hiromichi in his studio at home. Ōsaka says he is never happier than when he is absorbed in his work.

After carving the lattice, Ōsaka uses a small tool to smooth out the surface of the wood.

When carving a piece from a single piece of wood, the slightest mistake can been disastrous. Ōsaka needs to make sure he gets everything absolutely right every step of the way.

Boxwood incense container with filigreed latticework and hōsōge-style arabesque patterns (2011). This is Ōsaka’s most recent piece.

The lotus-flower design on the lid is carved out of a single piece of wood. The beauty of the minute details is breathtaking.

Writing brush box inlaid with arabesque-style patterns (1997). Tin inlay on black persimmon wood.

Floral incense container made from boxwood inlaid with tin (2009).

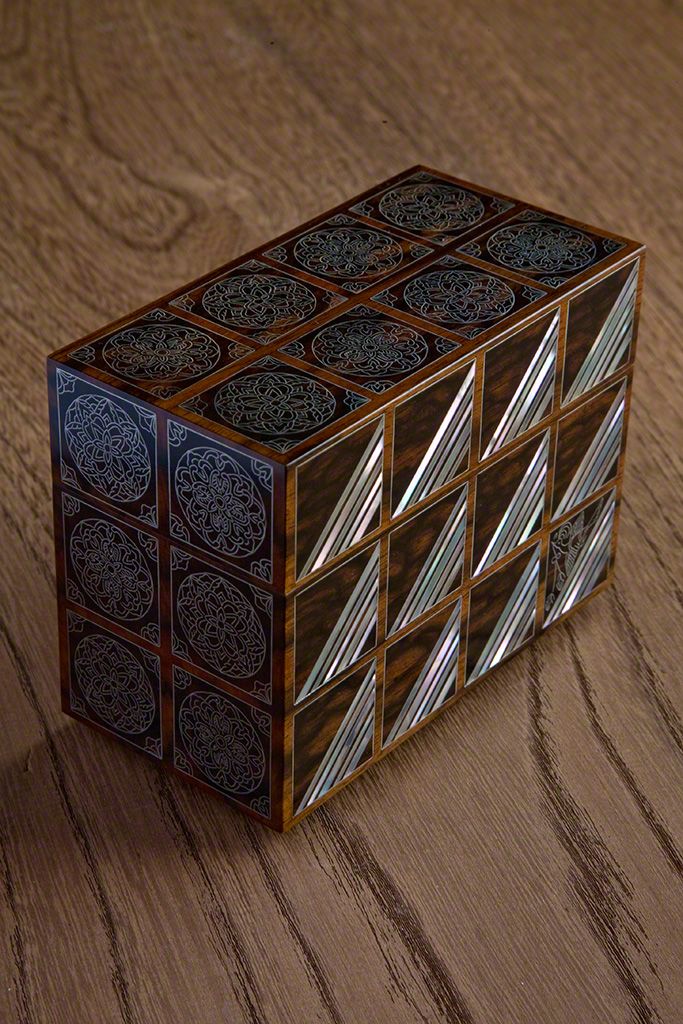

Raden incense box with inlaid arabesque-style patterns (2009). This piece features a base of black persimmon inlaid with tin and marbled turban shell. The straight lines of the inlaid shells immediately give the work a contemporary feel.

Design sketches. Ōsaka’s detailed sketches guide him during the painstaking carving stage of his work.

A work in progress: Ōsaka’s own funerary urn (kotsubako). For this piece, completed in 2003, Ōsaka used an alternating inlay of tin and gold to create an intricate arabesque pattern.

Ōsaka inserts the tin inlay into a piece of wood that will be incorporated into a design. This work requires remarkable precision—down to one tenth of a millimeter. These strips of wood are the building blocks of Ōsaka’s artistic vision.