Isezaki Jun’s Beautiful “Bizen” Pottery (Photos)

Culture Lifestyle- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

A Rustic and Earthen Aesthetic

Isezaki Jun

Isezaki Jun

Born in 1936 in Bizen, Okayama Prefecture; the second son of bizen potter Isezaki Yōzan. Studied fine arts at Okayama University and then spent one year as a high school teacher before becoming a potter. Designated as a living national treasure in 2004.

Isezaki Jun is one of the most renowned masters of bizen pottery, a traditional craft that emerged nearly a thousand years ago in the Inbe district of Bizen, Okayama Prefecture. His exquisite work as a potter has earned him the coveted title of “living national treasure,” bestowed by Japan’s Agency for Cultural Affairs.

Pottery workshops equipped with the kilns needed to produce the bizen style first appeared in the twelfth century, near the end of the Heian period (794–1185). Various utensils and containers were made in these workshops and the ones produced in the Momoyama period, in the second half of the sixteenth century, were highly prized—as they are today—by proponents of the wabisabi aesthetic, particularly for use in tea ceremonies and other traditions.

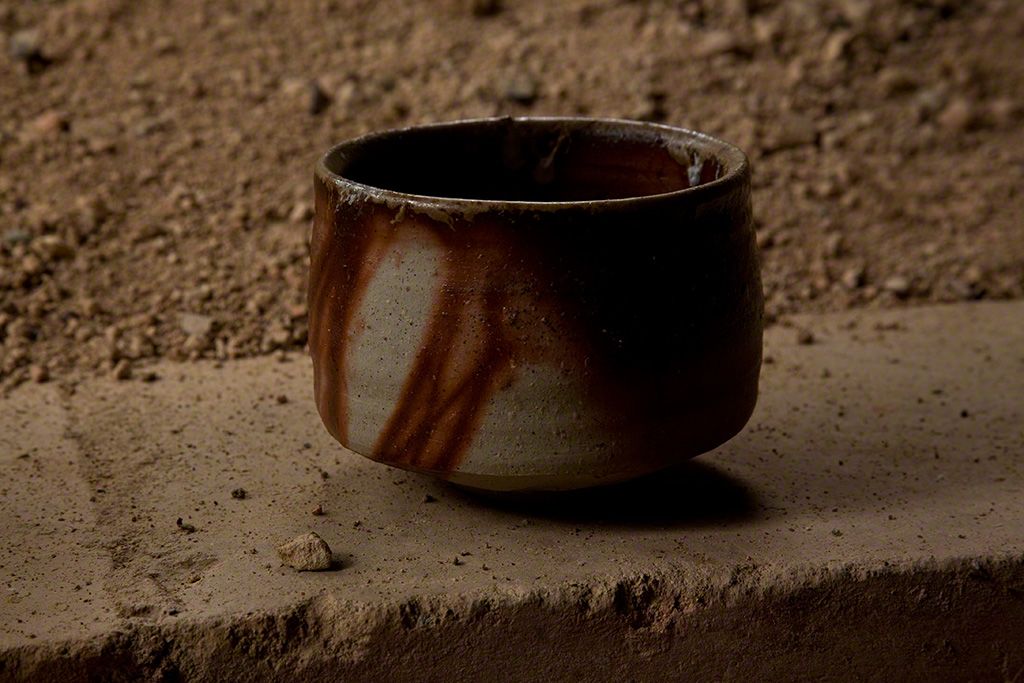

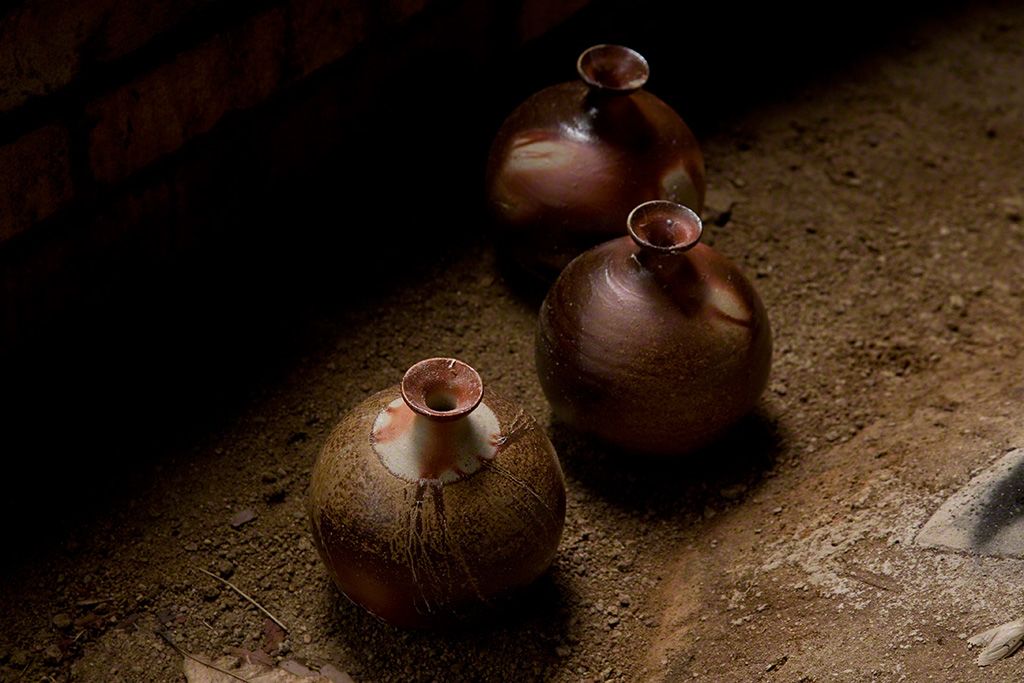

The appeal of bizen pottery lies in its tasteful, earthen feel. The pottery is never glazed and no designs are painted on the finished pieces. Each piece spends around two weeks in the kiln, and the color changes that take place during the firing process lie at the heart of the art form.

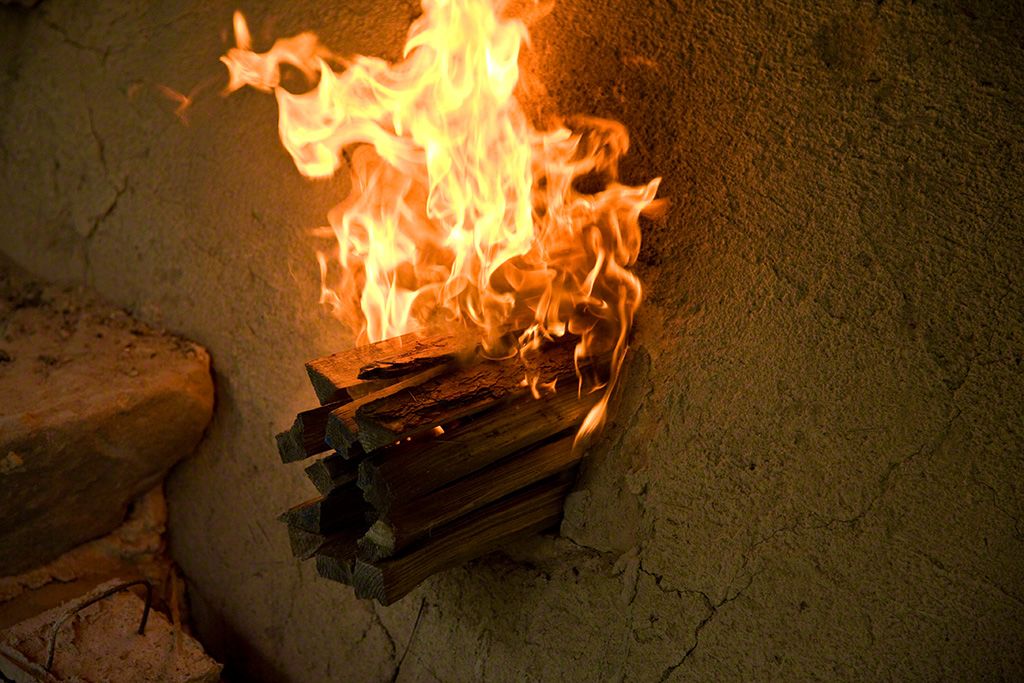

The clay used has a low resistance to heat and contracts a great deal so that sudden and extreme shifts in temperature can easily result in damage. This is why the firing process is stretched out over such a long period of time, gradually raising the temperature level.

The Element of Unpredictability

“The pottery slowly interacts with the blazing fire,” Isezaki points out. “Many unanticipated changes can occur inside the kiln, there are many changes that you cannot anticipate so there is a very deep and wide variety of expressions that can appear. That is not to say that everything is left to chance, however, as he goes on to explain:

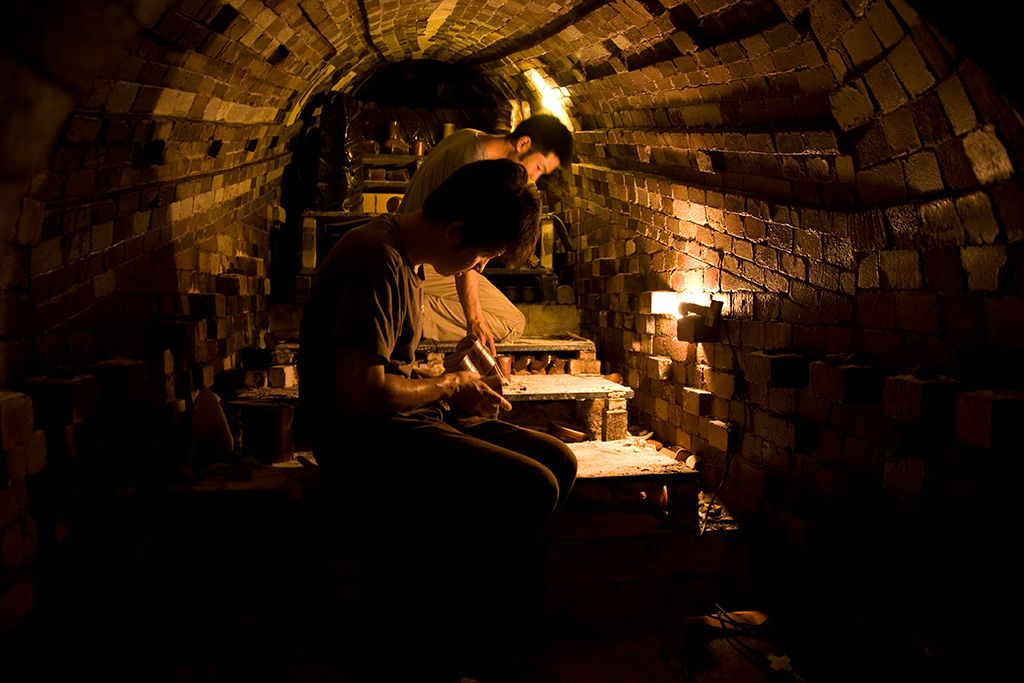

“The placement of the pieces inside the kiln is of crucial importance for bizen pottery. You need to work out how the flames will fire through the chamber and calculate where the ash is likely to fall. Putting the clay works into the kiln is like putting your creation in god’s hands. Sometimes a beauty emerges that couldn’t have been created by someone on their own. It’s a combination of the craftsman’s careful design and the randomness introduced by the firing process. When these two factors align, a truly satisfying bizen creation can emerge.”

The entire process—from putting the clay works into the kiln to taking them out again as finished products—takes around a month. Isezaki does this twice a year and says that, even after all this time, he is still nervous with anticipation when the day comes to remove the pottery from the kiln.

A Marriage of Creativity and Tradition

Isezaki is the fifth person to be designated as a living national treasure for work with bizen pottery.(*1) His unique characteristic is his modern take on this traditional craft. He has brought back the traditional kind of kiln used in the middle ages—a kiln that is dug into a hillside like a tunnel. For the past hundred years or so it has been more common to instead use a “climbing kiln,” built on the top of the slope, which makes it possible to produce a large amount of pottery with a consistent quality. In order to bring back the earlier type of kiln, Isezaki thoroughly researched the history and spent time learning from great artists like Isamu Noguchi (1904–88) and Ikeda Masuo (1934–97).

He continues to break new ground in his craft, with creations ranging from traditional tea ceremony implements to larger objects and installations. The bold, new forms that he creates year in and year out have captured the attention of artists in Japan and around the world. But his own creativity is rooted in the traditions of bizen pottery, as he explains:

“It was through many years of hard work that my predecessors pioneered the methods of bizen pottery used today. They managed, through that struggle, to overcome the weaknesses inherent to clay. This tradition built up over the years is essential. I believe that it is precisely through tradition that we can discover new possibilities for bizen pottery.”

Isezaki continues to seek to new ways to express himself in this artistic medium, thereby passing on to the next generation a legacy that they can build upon.

A tea bowl that has just been taken from the kiln.

Isezaki (left) keeps a close eye on the inside of the kiln.

The “hidasuki” markings resulting from the chemical reaction between the iron in the clay and the straw in the kiln.

Containers being fired inside the kiln.

Red pine inserted to fire the kiln—its high resin content helps the fire burn strongly.

Putting more wood into the kiln—a process that lasts two weeks.

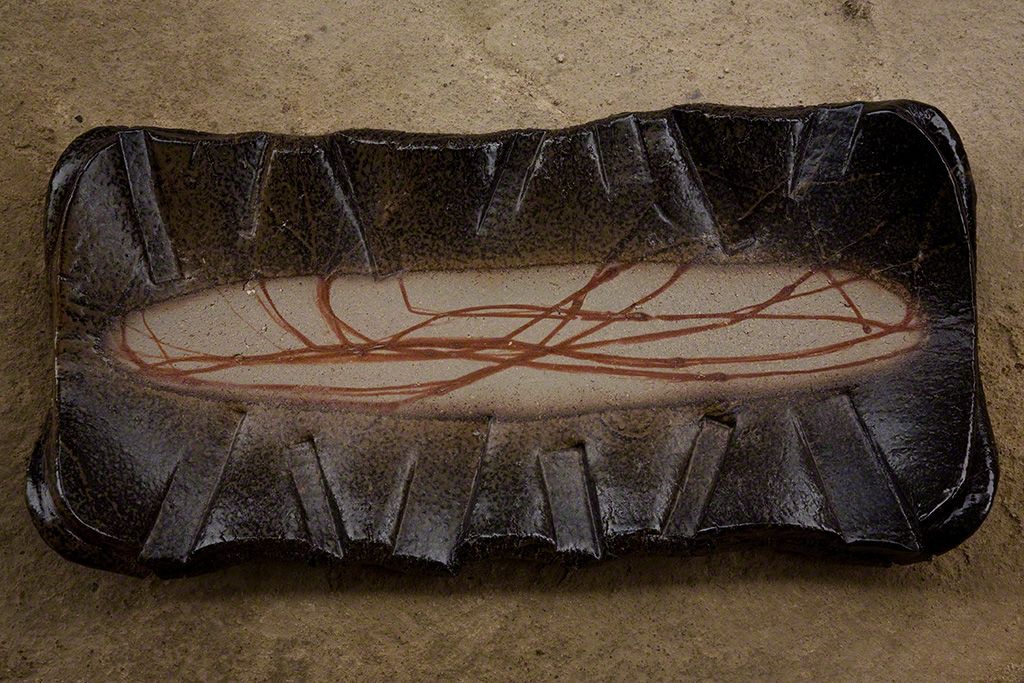

A large plate with the characteristic reddish-brown markings.

Wood is added and clay creations near the opening of the kiln are taken out and checked.

A tea bowl that was taken out in the middle of the firing process.

A pot with the distintive rustic, earthen feel of “bizen” pottery.

Another tea bowl taken out half way through the process.

A round plate with the characteristic markings.

Pottery is taken out of the kiln.

Isezaki looks on as the items are removed from the kiln.

Sake bottles fresh from the kiln.

Isezaki enters the kiln after it has cooled down to check his creations.

A long, thin plate in the “bizen” style.

Sake bottles just removed from the kiln.

The clay used to make “bizen” pottery, collected from the earth beneath rice fields.

An offering to the gods placed above the opening to the kiln.

Isezaki’s kiln, which he uses twice a year.

Isezaki with one of his creations.

(*1) ^ The four other living national treasures are Kaneshige Tōyō (1896–1967), Fujiwara Kei (1899–1983), Yamamoto Tōshū (1906–94), and Fujiwara Yū (1932–2001).