An Ode to Parents and Children: Photographer Bruce Osborn’s “Oyako” Family Portrait Project

Lifestyle- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

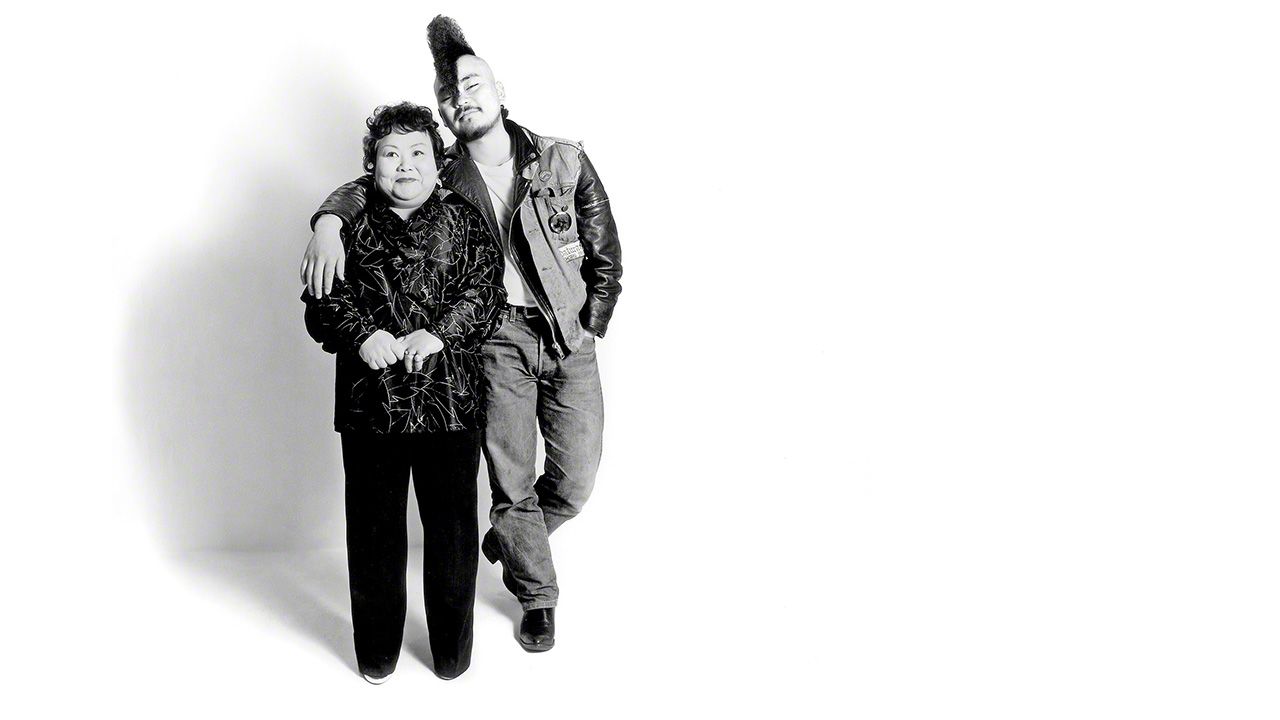

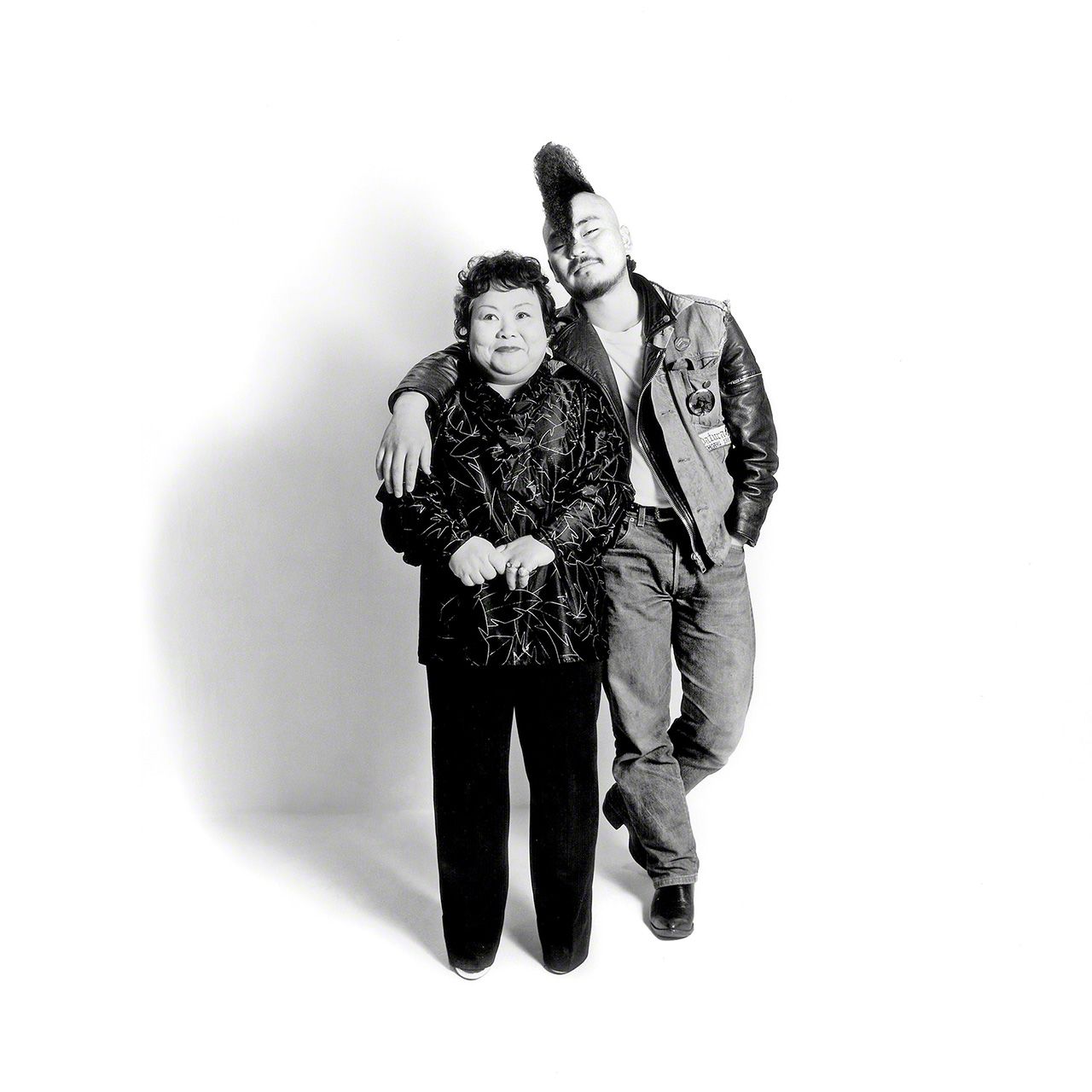

Back in 1982, a magazine commissioned Bruce Osborn to take portraits of Japanese punk rockers. At the time, it was just one among many jobs for the Tokyo-based photographer and director, but Osborn came up with the unusual idea of photographing the leather-clad musicians with their conventionally dressed parents. It was the beginning of a project that would end up his life’s work.

Thirty-seven years and over 7,500 portraits later, Osborn’s “Oyako” project—named with the Japanese word for “parents and children”—is still going strong.

In October 2018 Osborn published a book, Oyako: An Ode to Parents and Children, containing 88 of his favorite portraits from the series. There are photos of Buddhist monks and housewives, tea ceremony instructors and lawyers, sumō wrestlers and office workers. Many of his subjects are unknown members of the public, but some others are very famous indeed.

Parent: Nomura Mansaku, kyōgen stage actor. Child: Nomura Mansai, Kyōgen stage actor.

Parent: Kagenaka Taijun, Buddhist monk. Child: Kagenaka Akira, Buddhist monk.

Parent: Watanabe Sōgetsu, tea ceremony instructor. Child: Mitsui Keiko, tea ceremony instructor.

Parent: Kida Mitsunari, former sumō wrestler and restaurant owner. Child: Kida Tsuyoshi, preschool student and future sumō wrestler.

Kabuki actor Ichikawa Danjūrō XII is included with his son Shinnosuke. (The elder Ichikawa passed away in 2013 and his son is now Ichikawa Danjūrō XIII). Another portrait is of butō dance legend Ōno Kazuo with his son Yoshito. There is even a portrait of two people costumed as Hello Kitty and the superstar cat character’s mother, Mary White.

Parent: Ichikawa Danjurō, kabuki actor. Child: Ichikawa Shinnosuke, kabuki actor.

Osborn chose to take all the photographs in monochrome with a simple white background. He wanted to “keep the focus on the parent and child and their relationship,” he says.

“The other good thing about taking the photos in an empty studio is that it’s a new and different experience for them,” says Osborn. “Even though they might not physically look like each other, you can see something similar that they share—little things, like laughing or being embarrassed.”

Parents: Ōwada Mitsuaki, tattooist, and Akie, housewife. Child: Ōwada Keiko, elementary school student.

Parent: Koike Takeshi, farmer. Child: Koike Yoshihisa, policeman.

Parent: Sheena, rock musician. Child: Ayukawa Junko, high school student.

A Jazz Session

While some subjects pose formally in the manner of family portrait at a neighbourhood photo studio, others have been caught in exuberant motion.

“I don’t like to direct them too much and want their poses to be unrehearsed,” says Osborn. “Like musicians having a jam session, there is a rhythm when taking the photos; the music is playing, strobes are flashing, their movements begin to get in sync with the beat and my camera shutter. We get into a groove together.

“We’re enjoying taking photos together and their actions become more spontaneous. If they are smiling or laughing, it’s not only shown in their expressions; you can see it in their eyes and feel it in their whole body.”

In one portrait, the photographer Yokoyama Taisuke is leaping over the head of his high-school student son, Tai. In another, the interior and graphic designer Yamada Noboru is doing a little dance while his daughter Shinobu, also a high-school student, curls up with laughter.

Taken over almost four decades, the photos are a record of changing Japan, at turns ordinary and extraordinary, traditional and modern. There is a portrait of bald and bull-necked Iwahashi Ken’ichirō, formerly leader of Japan’s largest motorcycle gang, with his father Tatsurō. Perhaps the most striking portrait is of Suenaga Yōzō, a pet shop owner dressed in a crumpled suit next to his completely naked daughter, Momonoki Mai, an adult film actress.

Right at the front of Osborn’s book are four portraits taken at decade-intervals of Nakano Shigeru, one of the original punk rockers from the dawn of the project, and his mother Yae. The punk fashions change, but the love between mother and son is just as visible in 2012 as in 1982.

Parent: Nakano Yae, housewife. Child: Nakano Shigeru, musician.

Oyako Day

In 2003, Osborn’s project took a fresh turn with the inauguration of “Oyako Day,” held on the fourth Sunday in July each year. (The date was chosen because it follows Mother’s Day and Father’s Day.) On the first Oyako Day, the Osborns invited 100 families to have their photos taken. After the success of this first year, they have continued inviting 100 families every year since.

“More than anything, we wanted to express our gratitude to the families that we have met through this project,” says Osborn. “We hoped it would provide an opportunity for all of us to re-examine and reaffirm this bedrock relationship that our lives are tied to.”

Meanwhile, other photographers have joined the project. This year—the seventeenth Oyako Day— over 50 will run their own Oyako photo sessions.

In 2011, Osborn found himself taking a quite different kind of family photo. Following the disaster that struck Tōhoku in March that year, he asked to photograph families whose homes had been destroyed by the tsunami.

“I realized that I needed to go there and take oyako photos to give to the families . . . something they could have to look back on and remember how they worked together to rebuild their lives.”

He decided to take the photos in color and at locations that had special meaning for the subjects: a family on a lot where their home had once stood; fishermen in front of boats that were washed up on the streets; a gas station owner whose business was destroyed and was filling up cars tanks with gasoline from 20-liter containers in the back of his truck.

“I have since gone back several times to take more photos of the same families to show how things are changing with them and their communities,” says Osborn.

Parent: Yamada Jisaku, sushi chef. Child: Yamada Eiichi, sushi chef.

Parent: Suzuki Katsuji, carpenter. Child: Suzuki Katsuo, junior high school student.

Parent: Nakamura Yūjirō, theater group leader. Child: Matsumoto Rika, acting school student.

Two People, One Word

Having grown up in the United States before living in Japan for many years, Osborn sees differences between the parent-child relationships in his old and new homes. For example, Japanese has a single word for parent and child: oyako, composed of the characters 親 (oya, “parent”) and 子 (ko, “child”). There is no single-word equivalent in English.

“I felt it was an indication of the different way that these languages saw this relationship,” he says. “In Japanese, parent and child are combined into one unit, but in English, they are as separate individuals.

“In America, parents want their child to able to stand on their own two feet. Like a lioness pushing the cubs out of their den, parents want their children to grow up strong and independent.

“In Japan, working together and supporting each other is important. Young children usually sleep with their parents and take baths together. As the parents get old, it’s the child’s turn to take care of them.”

Osborn believes that there is something to learn from both Japanese and Western ways of thinking and tries to find a balance between the two cultures. But he stresses that he wants his project to go beyond cultural differences.

“Even you don’t have children of your own, we all have or had parents who gave us the gift of life. We are connected to them in a long chain that goes back to the beginning of life itself.”

It wasn’t a coincidence that Osborn started his parent and child photo project just a few months before the birth of his eldest daughter. Today, both she and her younger sister help with the project (one is a designer and the other an illustrator.) Osborn’s wife Yoshiko, meanwhile, assists with the photo shoots, in addition to producing and coordinating Oyako Day.

“It is a real oyako project,” says Osborn. “And of course, whenever we are together, we like to take a family photo.”

Oyako: An Ode to Parents and Children

Photographs by Bruce Osborn

Sora Books, 2018

- Book information: http://oyako.org/en/news-en/2018/12/oyako-book-ode-parents-children/

- Bruce Osborn’s website: http://www.bruceosborn.com/

- Oyako Project site: http://oyako.org/en/about/

(Originally written in English. Banner photo: Punk rocker Nakano Shigeru and his mother Yae. © Bruce Osborn.)