Munakata Taisha: A Birthplace of Japan’s Ritual Practices

Culture History Travel- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

One morning in early 2016, I received a telephone call from a friend in Kyūshū who operates an event planning business. He wanted me to photograph the shrines of Munakata Taisha in Munakata, Fukuoka Prefecture. The timing was not good for me, as I was working hard preparing two shows I would be having in the spring. Besides, having spent eight years, from 2006 to 2014, documenting the cyclical reconstruction and reconsecration of Ise Jingū and Izumo Taisha, I felt I had had enough of shrines for a while.

Still, I did not want to brush off my friend, so I decided to do some research on Munakata Taisha. The more I learned more about the shrine’s history, the more I was fascinated by Okinoshima, an island that is one of the three sites making up the shrine. The island, untouched by civilization, is where Japan’s indigenous form of worship was born, and I felt that an unknown world was calling to me from across the water. Unable to wait a moment longer, I jumped on a plane bound for Fukuoka.

Off Limits to Visitors

Chartering a small boat, I arrived at Okinoshima on February 19. I had to undergo a purification ritual, which called for dipping myself in the sea stark naked. The frigid waters of the Genkai Sea stung my skin like a knife. Now I was ready to take photos on the island. A number of ancient prohibitions have protected this sacred spot, which is off limits to all but a few people. After the piercing cold of my immersion, my heart beat faster at the thought of what intimations of kami spirits I might encounter.

I set out for Okitsumiya, midway up the island’s slope, climbing steep stairs in dense forest. At the end of my climb, I came upon the shrine, standing all by itself in the shadow of huge boulders. The shrine office was occupied by a lone priest, who is relieved by a replacement after 10 days of praying and tending to the kami on the island.

Twelve Shintō priests, each staying 10 days at a time, take turns living on the island year-round. Every day, the resident priest purifies himself in the sea before heading to Okitsumiya. When seas are rough and travel is difficult, the priest remains on Okinoshima until his replacement can arrive. (© Masuura Yukihito)

Dense forest closes in over the path to Okitsumiya. (© Masuura Yukihito)

The clearing behind Okitsumiya has an even more mystical atmosphere. Sites of ritual ceremonies carried out from the mid-fourth century to the ninth century remain in a virtually untouched state. In the absence of shrine buildings, rituals were conducted atop rocks, within rock crevices, or in the open air. Fragments of votive offerings like magatama curved stones, mirrors, and earthenware are strewn about, although some objects remain intact. The strict prohibition against taking anything, not even a leaf or a pebble, off the island has been faithfully observed, and the relics remain undisturbed.

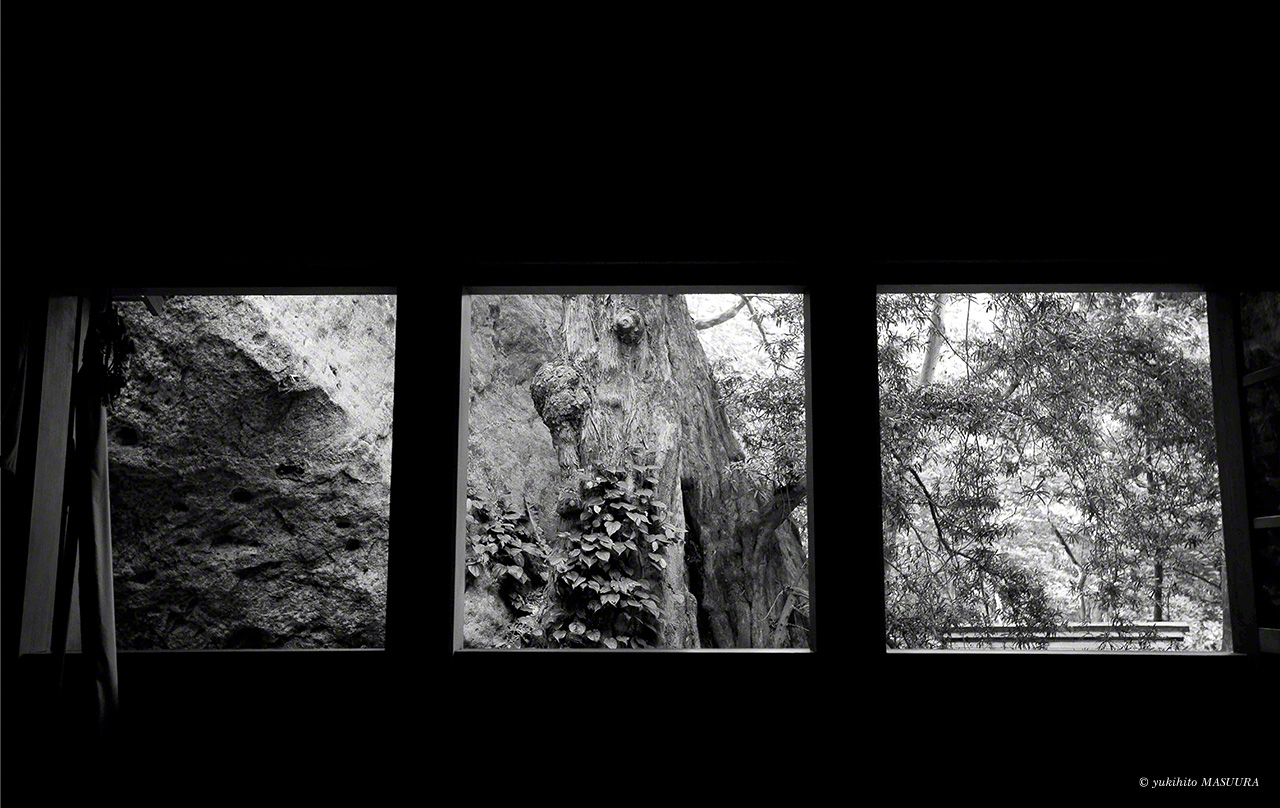

A view of huge rocks and virgin forest from inside Okitsumiya’s prayer hall. (© Masuura Yukihito)

Okitsumiya’s main hall, surrounded by boulders. (© Masuura Yukihito)

Votive offerings used for rituals lie scattered in and around ceremony sites. (© Masuura Yukihito)

Gilt bronze dragon-head ornaments excavated from a ritual site. Over 80,000 objects, collectively designated national treasures, have been found on Okinoshima. This has earned the island the name of “Shōsōin of the seas,” a reference to the eighth-century Nara repository built to store priceless historical treasures. (© Masuura Yukihito)

Coming upon these remains of these rituals, I had a gut feeling that the roots of native religious sentiment of nature worship lie in pure, unadorned sites like those on Okitsushima. Ancient Japanese had probably felt the presence of spirits everywhere, and I vowed to give an unadulterated view of prayer ceremonies carefully preserved for a millennium or more through my photographs.

Sacred island Okinoshima, a monolith between sea and sky. (© Masuura Yukihito)

Munakata Taisha: Preserving an Ancient Form of Prayer

A project to photograph all the works of Michelangelo had been in the works since 2000 but was on the verge of collapse and I was feeling stuck. In February 2001, I had my lens trained on a representation of Christ in a church in Rome when suddenly a ray of light came through a broken rose window in the ceiling and shone on the Christ figure. In that instant, I felt the presence of something invisible and yet palpably there. That experience later led me to Ise Jingū and Izumo Taisha, as well as to my fortuitous encounter with Okinoshima.

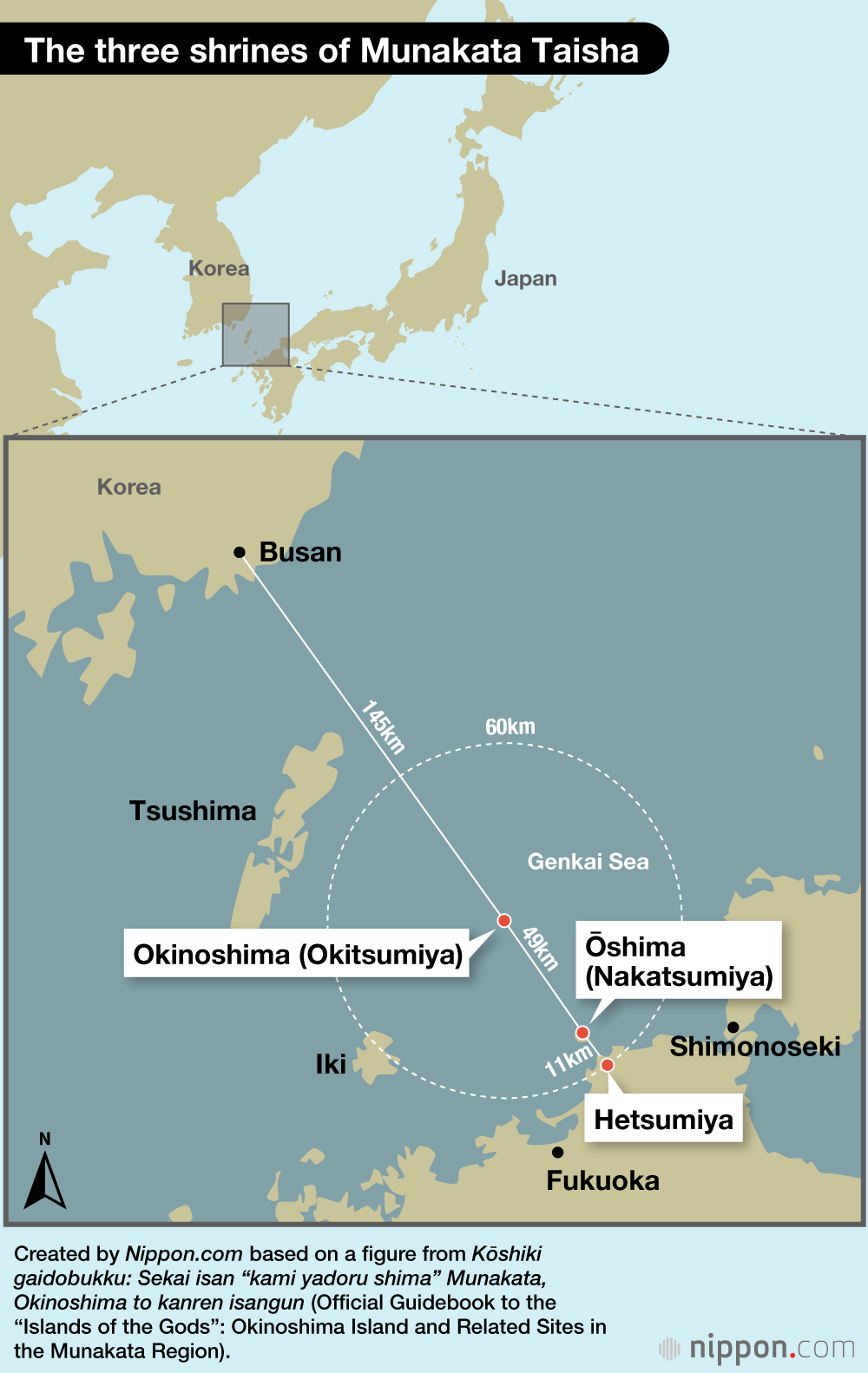

Beginning in the latter half of the seventh century, rituals similar to those on Okinoshima spread to Nakatsumiya on Ōshima, an island 49 kilometers away toward the Kyūshū mainland, and to Hetsumiya on Kyūshū itself, around 60 kilometers from Okinoshima. Those three entities compose the shrine complex known as Munakata Taisha. In recognition of Munakata Taisha’s great cultural significance, Okinoshima Island and Related Sites in the Munakata Region were inscribed as a UNESCO World Heritage site in 2017. My mission as a photographer was to convey images of these sites, untouched for over a millennium and the birthplace of the religious beliefs and prayer rituals of the Japanese people, to future generations.

The worship hall on the north side of Ōshima faces Okinoshima. Since members of the general public are not allowed on Okinoshima, they address their prayers to Okitsumiya here instead. (© Masuura Yukihito)

Inside Nakatsumiya’s worship hall on Ōshima. On clear days, Okinoshima is visible far across the water. (© Masuura Yukihito)

The shrine precincts of Hetsumiya on Kyūshū. The 108 spirits once worshipped at 75 of Hetsumiya’s subordinate shrines have been transferred to the main shrine. (© Masuura Yukihito)

The sacred oak standing beside Hetsumiya’s main hall was planted about 550 years ago. Its thick trunk attests to the passage of the centuries. (© Masuura Yukihito)

A dance performance in the Suki style at Hetsumiya’s spring festival. (© Masuura Yukihito)

Hetsumiya’s prayer hall is visible from the shrine gate. Behind it lies the inner shrine, where Ichikishimahime is worshiped. Munakata Taisha’s chrysanthemum crest features prominently on the gate. (© Masuura Yukihito)

The arched bridge over Shinji Pond amid blossoming cherry trees. The stone lanterns in front of the torii gate were a gift from Idemitsu Sazō, founder of petroleum company Idemitsu Kōsan. (© Masuura Yukihito)

The Takamiya ceremony site, in the rear of Hetsumiya’s vast grounds. The open-air site, said to be where Ichikishimahime alighted to Earth, exemplifies Japan’s ancient form of indigenous worship. (© Masuura Yukihito)

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: Okinoshima. The entire island, 4 kilometers in circumference, has been worshipped as sacred since ancient times. All photos © Masuura Yukihito.)