Sacred Beasts: Hunting for Traces of the Vanished Japanese Wolf

Environment History- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Nihon Ōkami

Wolves—in Japanese, ōkami, with the scientific name Canis lupus hodophylax—once roamed the mountains and forests of Japan. Residents in remote communities both revered and reviled the fierce creatures: Wolves were known to attack horses and riders, but the marauding packs also kept the crop-damaging hordes of wild boar and deer in check. Wolves were thought by some to have supernatural powers, and in certain areas they were even worshipped as divine messengers of the mountain gods themselves.

The once abundant wolf, however, disappeared entirely from Japan a little more than a century ago. The last known living specimen met its fate on January 23, 1905, at the hands of hunters in the remote village of Higashiyoshino in the mountains of Nara Prefecture. Surveys were conducted in the hope of uncovering traces of the animal, but these yielded no evidence, and the Japanese wolf was officially declared extinct. But is it really gone? Even today, people in the mountains report seeing wolves or hearing howls. Such stories compel those convinced of the wolf’s survival to journey in the wilds in search of the mysterious creatures.

Much to my surprise, I learned that scores of sightings are reported in the rugged Okuchichibu and Okutama areas to the west and northwest from central Tokyo, a region with a long tradition of worshiping the Japanese wolf. The possibility that wolves still roam the hinterlands fringing Japan’s sprawling capital captivated me. I feel certain that as symbols of nature’s unfettered energy, their rediscovery would help reconnect residents of the metropolis with a primordial side of their being that has been eroded by city life.

For all my efforts, though, I have never seen or heard a wolf. But I remain vigilant, praying that the animals still prowl Japan’s mountains, hiding just out of sight and beyond earshot.

There are tales from around Japan of okuri ōkami—mystical wolves that appear at night to escort travelers safely to their destination. A person confronted by such a beast is torn between feelings of gratitude and paralyzing fear, for while the wolf keeps the spirits of the night at bay, it may also pounce on wayfarers should they stumble or fall on the path. Such conflicting images of the Japanese wolf—benevolent and menacing—make it hard to know the true nature of the animal and the relationship people in the past shared with the creatures.

In seeking out traces of the wolf, I wanted to convey some of the spirit of the Japanese people of yesteryear who coexisted with these mysterious, dualistic animals.

I snapped this photo on my first visit to the mountains of Chichibu in Saitama Prefecture after hearing of a sighting in the area from the head a nonprofit organization dedicated to finding Japanese wolves. Looking down at the river Arakawa snaking through the town, it was easy to imagine a wolf gazing across the same scene.

Wolves stand guard at a small Shintō shrine in the Chichibu mountains near the headwaters of the Arakawa. Some 20 such shrines dedicated to wolves dot the area and attract parishioners seeking to ward off calamities like fire and theft, as well as to safeguard crops against pests like deer and wild boar.

An abandoned residence on land that was once the domain of Mitsumine Shrine, deep in the mountains of Saitama Prefecture. Residents were parishioners of the shrine, an ancient center of wolf worship, and made their living tending the surrounding forests.

Wolves devour their prey bones and all. Japanese folklore tells of one greedy creature vexed at finding a bone lodge in its throat. Seeking relief, the wolf beseeches a villager, who reaches into the beast’s mouth to remove the errant bone. Relieved of its troubles, the wolf bows its head and departs, returning the following day carrying wild birds and a deer shank in its jaws as an expression of thanks.

The path to the Okumiya, or innermost sanctum, of Mitsumine Shrine climbs through thick forest. Travelers along the route frequently report hearing howls in the distance.

A stone wolf guards the entrance to Jōmine Shrine in the mountains of Saitama Prefecture.

Japanese folklore describes travelers being accompanied by wolves as they pass through the mountains at night on their journey home. Such wayfarers would step carefully as they made their way to their destination, fearful of being devoured by the beast if they were to stumble and fall. Upon arriving, they would turn to the wolf, thank it for keeping the mischievous spirits of the night at bay, and bid it to go on its way, offering gifts of salt and rice gruel flavored with adzuki beans.

Bones of a Guardian

Visiting a home in the Shinazawa area of Chichibu, I am confronted by an ancient skull of a wolf. Considered a holy item, it belongs to an animal shot during the late Edo period (1603–1868) by an ancestor of the household five generation earlier. According to local belief, wolves are messenger of the gods. To atone for killing the hallowed beast, the family renounced hunting all together, a resolution it still observes to this day.

Even into the early years of the twentieth century, people kept the skulls of wolves and foxes as charms to ward off evil spirits. Looking closely, I see the old bones have been ground smooth in places. In the past, powder made from these skulls was considered a potent medicine for treating fever.

The Taki River flows through Okuchichibu. Some 60 years earlier, two fishermen returning from a nighttime outing in the area reported seeing a line of six or seven wolves emerge from the surrounding forest and pass by without concern for the intruders.

Looking back over the Chichibu mountains from the Okumiya of Mitsumine Shrine. Beyond, the peaks give way to the Kantō Plain and the waters of Tokyo Bay.

Wolf Hunting

In 1969, Yagi Hiroshi was spending the summer tending a cabin for hikers in Naeba in the mountains of Niigata Prefecture. One evening, Yagi, then 19 years old, set off on the chore of lugging a 30-kilogram bag of rice to reprovision a hut at the top of the mountain. While walking on the trail under the full moon, he heard what eerily sounded like the howl of a wolf in the distance. Terrified by the cry, he turned on his heels and hurried back down the path, taking refuge in the cabin until daybreak.

He completed his delivery the following morning, but subsequently missed the bus he had hoped to ride to the base of the mountain. He sat lamenting his luck when news reached him that the vehicle had veered off the road and plunged down a cliff. The act of providence was unmistakable: the howl the previous evening had spared his life. Convinced of the existence of wolves, he has spent over five decades searching for traces of the creatures.

On October 14, 1996, Yagi was scouting the mountains of Chichibu when he encountered an animal resembling a wolf and managed to snap a series of photos. Prominent Japanese zoologist Imaizumi Yoshinori studied the images and determined that the creature shared 12 characteristics with a type specimen, used when a species is first identified, of a Japanese wolf kept in Leiden, the Netherlands. Although the evidence was not conclusive, the animal was given the name Chichibu yaken—the “wild dog of Chichibu.”

Since then, Yagi has collected more than 200 accounts of sightings and other reports. In 2010, he founded a nonprofit organization dedicated to uncovering evidence of Japanese wolves. Members of the group have installed upward of 90 camera traps in the Okuchichibu area and conduct regular forays into the mountains.

In May 2002, Yagi was surveying this stretch of the Nakatsu River basin when he discovered several canid-like paw prints measuring 7–8 centimeters and the partially devoured carcass of a serow, a sort of mountain goat. As he investigated the scene, he says the hairs on the back of his neck suddenly stood on end and that he was overcome by the feeling that a fierce animal was behind him, watching.

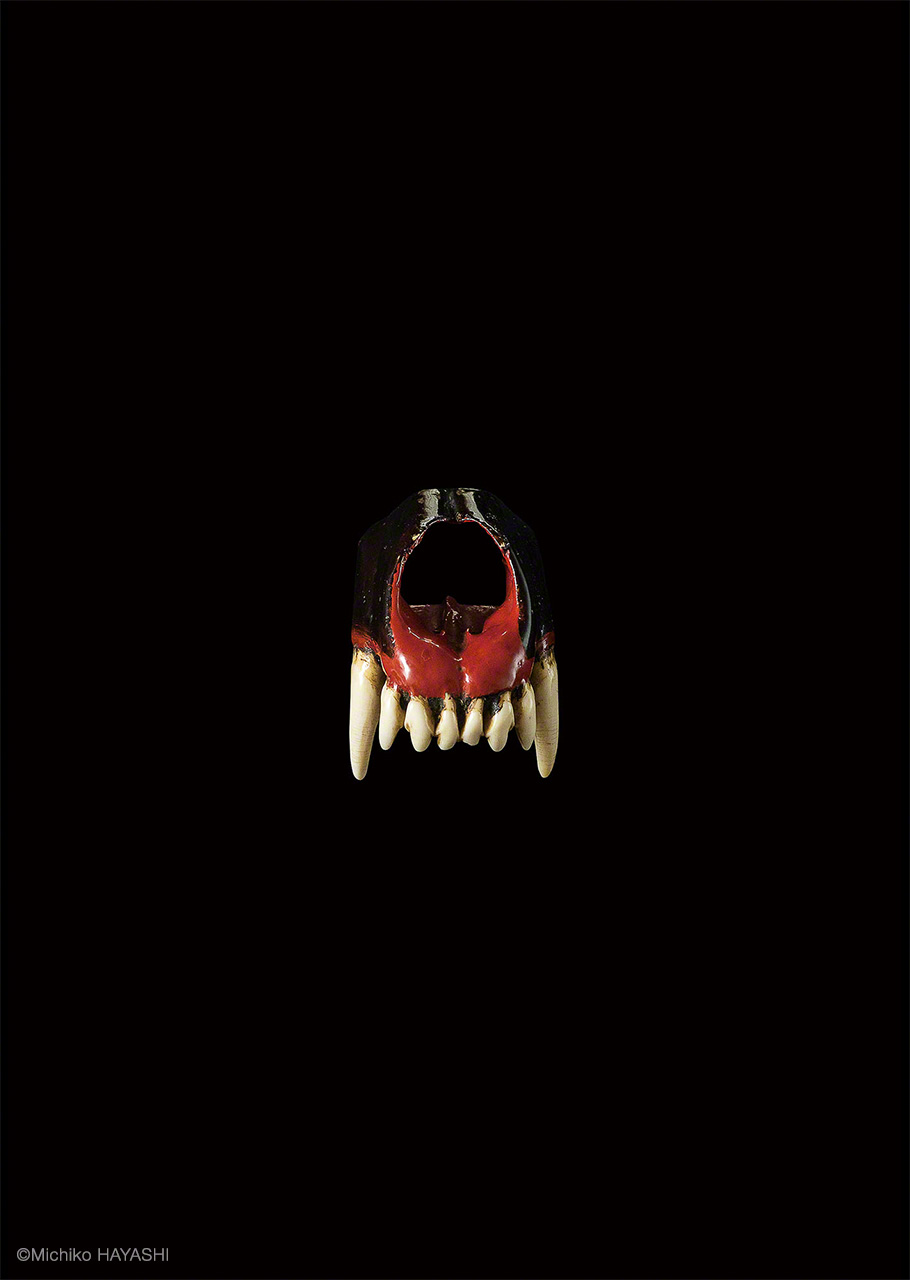

The partial upper jaw and teeth of a young male wolf killed near Mount Mitsumine in Okuchichibu. Painted with lacquer, the specimen belongs to a family in Sayama at the foot of the Chichibu range in Saitama Prefecture. It was purportedly a gift from the lord of the domain many generations back and was brought by the grandmother when she married into the family.

The full moon shines above Minoyama in Chichibu. A nearby hallow named for wolves is where the animals are thought to have had a den and raised their pups.

Telling the Hodophylax Tale

In 2016 I began thinking about how to tell the story of the Japanese wolf, a creative task made all the more challenging by the physical absence of the subject. In May of that year, I participated in a photobook workshop put on by Reminder Photography Stronghold, a curated membership gallery in Tokyo. The experience served as a springboard for creating the artist’s book Hodophylax: The Guardian of the Path, which went on sale in January 2017. I made 111 copies of the work to mark the number of years that had passed since the last Japanese wolf was captured in 1905 and the start of my project.

In the meantime, investigations of the Japanese wolf have steadily progressed. A recent project by the National Museum of Nature and Science in cooperation with several Japanese universities has used ancient DNA to help shed light on the origins of the Japanese wolf. In 2018, Yagi’s group recorded a howl that the Japan Acoustic Laboratory analyzed and found to closely resemble that of the eastern wolf, a small species native to the Great Lakes region of Canada, raising the prospect that the cry came from a Japanese wolf. Such news fills me with excitement for new discoveries that are certain to come in the days and years ahead.

Thanks to interest in the topic, the initial 111 copies of Hodophylax sold out. Like the creature that inspired the work, I hope to see it return someday.

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: Part of an upper jaw of a Japanese wolf owned by a household in Sayama, Saitama Prefecture. All photos © Hayashi Michiko.)