Glimpses of a Glittering North: Mizukoshi Takeshi’s Hokkaidō Photography

Hokkaidō Animals in Their Element

Environment- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Nature in Hokkaidō is completely different from that of Japan’s main island Honshū to the south. During the last Ice Age 20,000 years ago, sea levels dropped by 100 meters and Cape Sōya, the northernmost point in Hokkaidō, became a land bridge over which animals from the Eurasian continent crossed over. But the Tsugaru Strait, which separates Hokkaidō from Honshū, is 400 meters deep and its waters are swift. This prevented wildlife from crossing to Honshū, and thus many species living in Hokkaidō are endemic to that region. This zoogeographical boundary is known as “Blakiston’s Line,” after the English naturalist Thomas Blakiston (1832–91), who was the first to notice this phenomenon.

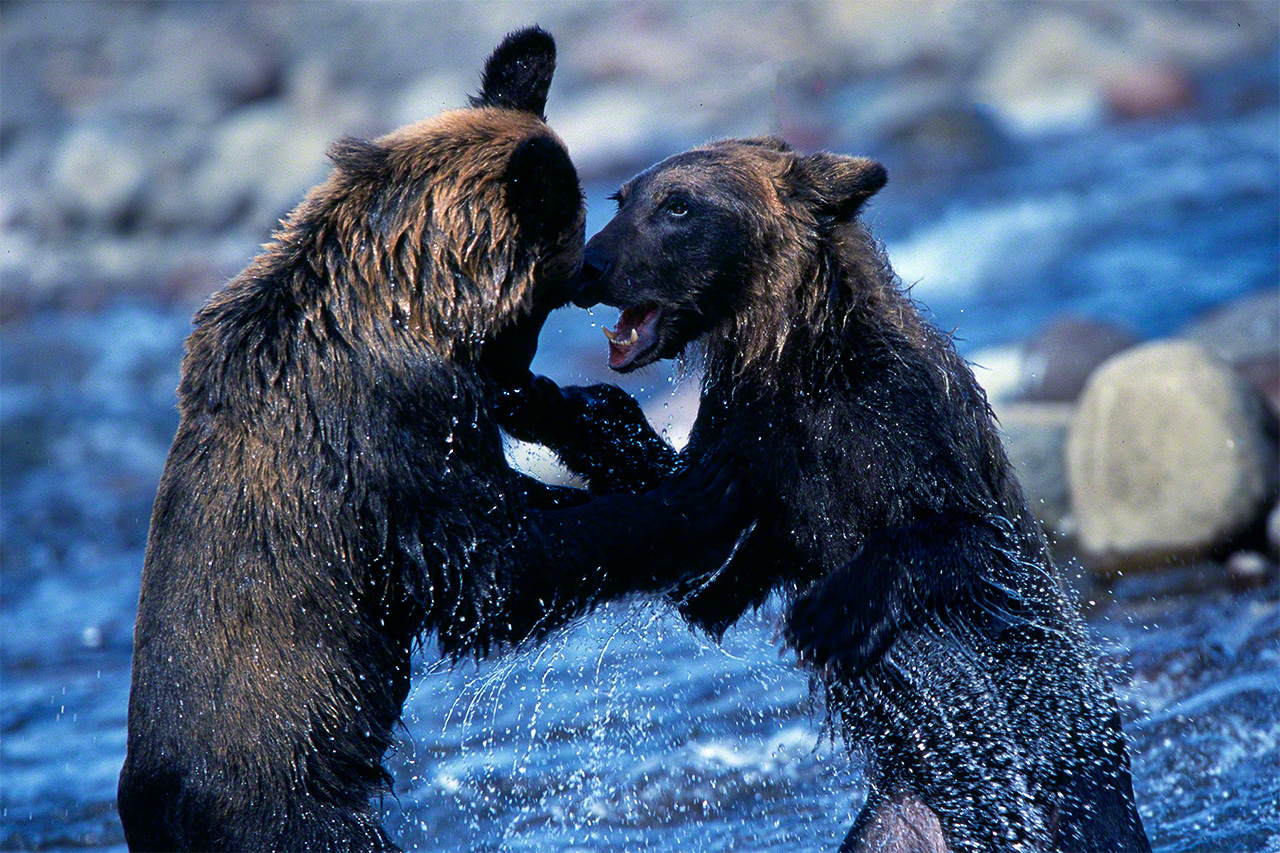

The Omnivorous Brown Bear

Two bear species are found in Japan: the Asian black bear south of Blakiston’s Line, and the brown bear north of the Line. Brown bears are omnivorous. Ninety percent of their diet consists of plants, but they also eat salmon and trout swimming upriver, ants and other insects, as well as animals such as the Yezo sika deer which have become plentiful in recent years. After accumulating sufficient fat, the bears hibernate over winter; females give birth to one or two cubs in their dens during that time. The cubs emerge from the den in April when the snow has melted and remain with their mother for the first year. After hibernating again that winter, the cubs begin to live independently the following spring.

Brown bear cubs sparring playfully. (© Mizukoshi Takeshi)

Mother and cubs on the lookout for salmon and trout. (© Mizukoshi Takeshi)

Brown bears are present only in Hokkaidō now, but fossils of these bears have been found on Honshū. Masuda Ryūichi, a specially appointed professor at Hokkaidō University whose specialty is zoogeography, has analyzed the DNA of Hokkaidō brown bears and identified three lineages—southern Hokkaidō, eastern Hokkaidō, and central and northern Hokkaidō. The southern Hokkaidō lineage is a close relative to the fossils found in Honshū, and although there is no definitive proof, this lineage may have traveled from the Korean Peninsula across the Tsushima Strait to Japan and crossed Blakiston’s Line into Hokkaidō millennia ago.

I myself have never seen southern Hokkaidō brown bears, but I have heard that they show some differences in size and temperament compared to their brethren to the east and north. Knowing that it is now possible to trace the path of ancient bears right up to their travels from the Eurasian continent adds a romantic dimension to scientific research.

A brown bear napping peacefully. (© Mizukoshi Takeshi)

The Owls of Hokkaidō

Several owl species live in Hokkaidō, ranging from abundant Yezo Ural owls, horned owls, and oriental scops owls to the rarely seen snowy owl and eagle-owl.

A Yezo Ural owl in winter. (© Mizukoshi Takeshi)

Blakiston’s fish owl, designated a national treasure by the central government and found only in Hokkaidō, has a wingspan of nearly two meters. Japan’s largest species of owl, this majestic bird is regarded by the indigenous Ainu people as kotan kor kamuy (the god that protects the village).

I once encountered a pair of Blakiston’s fish owls in a small valley in the mountains of Shiretoko. As I retreated to my tent and the sun went down, I remember fondly how I was lulled into a deep sleep by the owls’ voice sounding like a lullaby to my ears.

A Blakiston'’s fish owl naps atop a branch in the daytime. (© Mizukoshi Takeshi)

Owls fly silently as they home in on their prey. Even the huge Blakiston’s fish owl glides noiselessly through the night sky. (© Mizukoshi Takeshi)

A Blakiston’s fish owl sinks its claws into a trout. (© Mizukoshi Takeshi)

The red-crowned crane is the unparalleled symbol of Hokkaidō. Although some sightings of the bird were even reported in Honshū during the Edo period (1603–1868), it was believed to have become extinct early in the twentieth century. But in 1924, a dozen or so specimens were discovered living in the far reaches of the Kushiro marshes. Preservation efforts have been fruitful and today, this crane can occasionally be seen in places other than in eastern Hokkaidō too. A century after the birds were rediscovered, their population has now grown to 1,927 individuals as of January 2025.

A red-crowned crane soars high above. (© Mizukoshi Takeshi)

A family of red-crowned cranes in a snowy field. (© Mizukoshi Takeshi)

The cranes’ mating dance. The birds mate every year around February. (© Mizukoshi Takeshi)

In the Ainu language, the Yezo sika deer is called yuk. The word, which means “prey” or “meat,” indicates that these deer were a food source for the Ainu. Extinction loomed after massive snowfalls during the Meiji era (1868–1912), but herds have grown explosively in recent years with the increased availability of grasslands. Nowadays, however, the increase in the deer population is not always welcome, due to problems such as car accidents and trampling and grazing on farmland.

Sika deer under a full moon. (© Mizukoshi Takeshi)

Sika deer dash across the frozen surface of Lake Fūren. (© Mizukoshi Takeshi)

Sika deer foraging for grass in the snow. (© Mizukoshi Takeshi)

Swans on Lake Kussharo in winter. (© Mizukoshi Takeshi)

Swans on a winter morning. (© Mizukoshi Takeshi)

Northern pika dwell in mountainous rocky areas such as the Daisetsuzan or Hidaka ranges. (© Mizukoshi Takeshi)

The Ezo wolf once roamed Hokkaidō’s forests and marshes but was driven to extinction by human activity during the Meiji era. Today, coming into contact with Hokkaidō’s animals in all their wild majesty reminds me that each species is irreplaceable.

(Originally published in Japanese on July 22, 2025. Banner photo: A brown bear catching a pink salmon. © Mizukoshi Takeshi.)