Japan’s Textbook Screening and History Textbook Controversies

Japan’s History Textbook System: Creation, Screening, and Selection

Politics Society- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

In this article I will offer a brief exposition of the way history textbooks are currently produced in Japan and how they are used in primary and secondary education. Though the characteristics of Japan’s textbook system have recently become well known among Japan specialists around the world, there seems to be considerable misunderstanding on the subject among historians not specializing in Japan and among the public.

Political and Social Background

Before I discuss the textbook system itself, I believe it would be helpful to touch on its political and social background. History textbooks currently constitute a delicate political issue involving an intertwined mix of international and domestic concerns in countries around the world. The intensity of the disputes over them waxes and wanes in response to the will of governments and civic movements, but they seem likely to remain a potential source of discord among nations for the foreseeable future. This is because of the tendency to view each country’s history textbooks as being written basically as “national history.” Their contents are seen as representing the national consensus on history with respect to both the country itself and other countries. People thus believe that these schoolbooks present the view of domestic and international history that the adult generations in each country seek to inculcate in their children as part of their education as members of the nation.

History textbooks first emerged as a source of international controversy in East Asia about a hundred years ago, but the present set of issues involving them originated in the 1980s. About 35 years after Japan was defeated in World War II and lost its colonial possessions, people in neighboring countries started to direct criticisms at its history texts. Asserting that these schoolbooks failed to present adequate accounts of Japan’s responsibility for its colonization of Korea and for the Sino-Japanese War of 1937–45, they started to demand that the texts be revised.

Now, however, the controversy in East Asia concerning historical perceptions has expanded beyond the sphere of pinning blame on Japan for past deeds. For example, since the start of the current century South Korea and China have taken to pressing competing claims to “ownership” of the historical kingdoms of Goguryeo (高句麗; also spelled Koguryo; Chinese name Gaogouli) and Balhae (渤海; also Parhae; Chinese Bohai). As this sort of controversy involves confrontation between two national histories, it presents a deeper set of problems than the concrete issues of Japanese responsibility for acts committed in the relatively recent past.

The controversy over history textbooks in East Asia encompasses a number of serious issues of this sort. Here, however, I will focus just on Japan, attempting to provide a systematic presentation of the basic facts required to consider the issue.

The Teaching of History at Primary and Secondary Schools in Japan

Japan’s public school system consists of elementary schools (six years), junior high schools (three years), and high schools (three years). History education starts in sixth grade, the final year of elementary school, with children learning about key figures in Japanese history. At the middle school level, history is taught as one of the fields in the social studies curriculum, along with geography and civics; all these subjects are required. The focus is on Japanese history, with some references to world history as background. Compulsory education end with middle school, but 97% of middle school graduates go on to high school. There the history curriculum is split between world history and Japanese history; the former is a required subject, but the latter is optional. So the emphasis is on Japan’s history at the elementary and middle school levels but switches to the history of other countries in high school.

The School Textbook System

Next I will describe the major features of the textbook system for public education in Japan. First, the use of approved textbooks is compulsory in elementary, middle, and high schools.(*1) Teachers may supplement these with materials that they prepare themselves or that are commercially available, but basically they are expected to follow the order and content of the prescribed textbook in their teaching. Japan’s history textbooks have been appraised as being relatively restrained in their presentation of political and ideological propaganda by comparison with those of other East Asian countries.(*2) In this respect, the constraints imposed by the official Courses of Study curriculum guidelines are an important influence on the structure of the historical image portrayed in the texts. Both the split between the history of Japan and that of other countries and the idea of Japan’s history as a continuum from ancient to modern times are firmly implanted in the minds of Japanese adults through public education.

A second feature of the system is the way textbooks are created and adopted: Multiple private-sector publishers draft textbooks and submit them to MEXT for screening; the ones that are approved may be used in schools. This screening system contrasts with the system of government-designated textbooks used in Japan before the end of World War II and in neighboring countries until recently. A pair of conflicting pulls can be observed in this process: the pursuit of uniformity by MEXT through its curriculum guidelines and screening of textbooks versus the independent initiatives and pursuit of diversity by schoolbook publishers and authors.

A third feature of the system is that the choice of schoolbooks for actual classroom use is made not by MEXT but by multiple actors. At high schools and at private elementary schools and junior highs the decisions are made by the school itself. Elementary schools and junior highs operated by prefectures or municipalities, are under the purview of local boards of education, but a system has been set up providing for “textbook selection districts,” within which all the schools use the same set of textbooks; as of 2011 the country as a whole was divided into 582 such districts of roughly similar population. So to sum up the features of Japan’s textbook system, the position that textbooks occupy in school education is very important here by global standards, and while private publishers create multiple textbooks independently, the screening process is under the centralized control of the national government, with selection of textbooks conducted at the local government level.

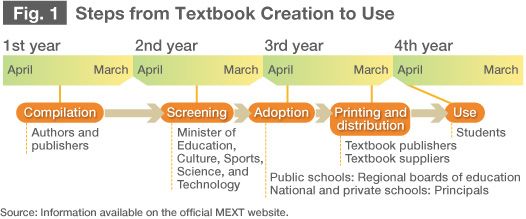

In what follows, I will explain the three stages leading to classroom use of textbooks, namely, creation by private publishers, screening by MEXT, and selection by schools and local government bodies.

Creation by Private Publishers and Authors

Textbooks in Japan are created and sold by private-sector publishers on the basis of the Courses of Study set by MEXT. Publishers generally revise their textbooks once every five years, starting work on the next edition in the year after a new edition starts being used in classrooms. The editorial committees for history textbooks normally consist of two or three employees of the publishing company along with history scholars from universities and schoolteachers responsible for history classes at junior high schools or high schools. In drawing up the table of contents, these committees refer to the MEXT Courses of Study, which stipulate textbooks’ purposes, the scope of their content, their structural framework, and their approximate volume. Textbooks that deviate from these MEXT standards will not make it through the screening process.

The Courses of Study, however, provide only a rough guideline, and so it is up to editorial committee to decide on the actual contents of the textbook. After determining the table of contents and assigning the authors their parts to write, the committee holds 10 or so meetings, at which the participants consider revisions on the basis of teachers’ experiences with existing textbooks and shifts in points of interest and perspectives that have arisen from changes in society. Key considerations include the question of where to place emphasis, ease of learning, ease of reading, and the selection of topics and expressions matching pupils’ level of mental development. Schoolbook publishers put together their drafts of new editions over a period of somewhat more than one year, completing the process two years before the new texts will start to be used. They then print and bind the new editions and apply to MEXT to have them screened.

Screening by MEXT

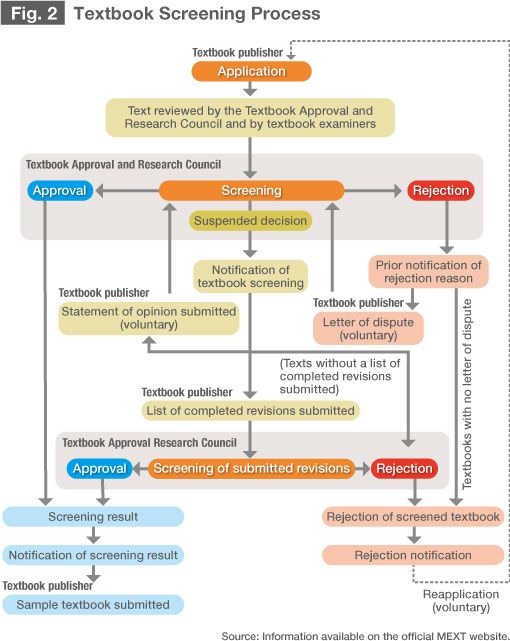

MEXT examines the draft textbooks prepared and submitted by publishers, and it approves or disapproves them. The procedures and standards for this process are determined on the basis of the ministry’s Textbook Examination Standards and its Courses of Study, and they are made public. Under these provisions the Textbook Approval and Research Council, an organ within MEXT, is responsible for examining the textbooks, and the minister of education, culture, sports, science, and technology decides whether to approve them or not on the basis of this council’s recommendations. In line with common practice in the Japanese bureaucracy, it is rare for a minister to overturn a decision by the council.

The council’s deliberations are conducted on the basis of studies prepared by textbook experts from within MEXT and outside researchers appointed by the ministry (there are several hundred of these outside researchers nationwide, consisting of classroom teachers from the university to elementary school levels). In practice, the MEXT experts consider the textbooks scrupulously, and their findings apparently carry great weight. The council issues its recommendations around November of the year in which the draft textbooks were submitted. If a textbook is approved, the applicant is notified immediately, but in almost all cases the council withholds its final decision and requests revisions. Sometimes textbooks are rejected, but in such cases the applicant is notified in advance, told the reasons, and given a chance to rebut and request reconsideration.

When a final decision is withheld, the council prepares an evaluation report listing the points on which it seeks revision and conveys this to the publisher and authors, accompanied by a verbal explanation from a MEXT textbook expert. Publishers may submit a formal objection to the evaluation report, but apparently in almost all cases they consider the contents of the report and submit a list of revisions. In theory there could be major differences of opinion between the council and the authors, but in practice most of the points cited in the evaluation report concern errors in objective matters of fact, orthographic mistakes, or vague or difficult-to-understand forms of expression, and publishers rarely object. The council then considers the revisions submitted by the publisher and issues a final decision in the minister’s name.

The Compulsory Education Textbook Examination Standards, which serve as the basis for the council’s decisions, consist of general items applicable to all subjects and items relating to specific subjects. The general items are as follows:(*3) (1) In terms of scope and degree of difficulty, all items specified in the Courses of Study must be included and no unnecessary items may be included. (2) In terms of selection, treatment, organization, and amount, (a) the textbook must not include content that is inappropriate in light of the Courses of Study or that fails to consider the developmental level of the students ; (b) the treatment of politics and religion should be impartial; (c) there should be no bias towards specific subjects, phenomena, or fields, and an overall balance should be maintained; (d) one-sided views should not be included without adequate safeguards; and (e) the overall amount of material and its allocation, organization, and linkage should be appropriate. (The final point probably relates to the fact that textbooks are distributed free of charge and the prices paid to publishers are fixed by the government—as of 2011, the price was ¥694 for junior high school history texts, less than half the normal price for other published works of the same scale—meaning that the total volume must be strictly limited.) (3) Textbooks must be accurate and use correct orthography and expressions. (As noted above, this is the item that is the source of frequent requests for revision in the examination process.)

In addition to the above, the following subject-specific items are applicable to social studies texts (except maps) for elementary and junior high schools: (1) Textbooks are not to include definitive statements about uncertain topical events. (2) Sufficient regard must be given to international understanding and harmony when dealing with modern historical events that involve neighboring Asian countries. (3) When quotes are taken from written works, historical materials, and the like, the materials used should be ones with established reputations and high reliability, and they must be handled fairly. When quoting legal documents, the original orthography is to be carefully preserved. (4) Important dates in Japanese history should be given in both Japanese and Western formats.

Overall, these examination standards demand that textbooks be as objective and balanced as possible. The standards applicable to texts for social studies courses, except for items (2), the “Asian neighbors clause,” and (4), the use of Japanese era names for years, may be considered sweeping directives, with the details specified in the Courses of Study. These fussy standards, along with the limit on volume, clearly have the effect of making Japan’s textbooks uninteresting as reading matter, but they seem to be well considered in terms of assuring procedural fairness. This assessment is confirmed by viewing the examination process in action, that is to say, the implementation of the standards.(*4)

In 2010 MEXT received applications for examination of eight junior high school history textbooks, of which it approved seven. After receiving notification of approval, the publisher produces and submits sample copies of the textbook; the following year these texts undergo a process of inspection and selection at the local level.

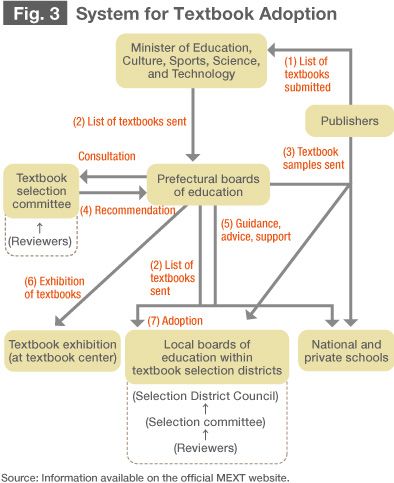

Selection at the Local Level

The next stage is adoption of textbooks for use in schools. It is only by clearing this hurdle that an approved textbook can actually reach the classroom and students’ hands. High schools can make their own selections from among the textbooks approved by MEXT, as can private and national elementary schools and junior high schools (private schools account for slightly over 6% of students at these levels and national schools for about 1%). But for prefectural and municipal elementary and junior high schools the selections are made by “textbook selection districts.” Under the Act on the Organization and Operation of Local Educational Administration, educational policy for public schools operated by local governments is determined by local boards of education, which are established at the prefectural and municipal levels and are composed of residents selected by local assemblies, but the textbook selection districts are established at an intermediate level between the prefecture and the municipalities; they generally encompass around three cities or gun (counties). As of 2011 there were 582 such districts in existence. Within each district a single textbook is selected and used throughout the district for each subject.(*5)) The selection process is conducted as follows:

A textbook selection committee is established in each prefecture, consisting of school principals, teachers, and academics. These committee members prepare selection reference materials on the basis of studies conducted by small groups of teachers for each subject, such as math and world history, and they then provide guidance and advice to those responsible for the final selection. In the case of prefecture-run schools (which include special-needs schools and combined junior-senior high schools), the committee’s input is directly reflected in the final selection. In the case of municipal schools included in selection districts (as most junior high schools are), a district selection council is established, and it makes the selections with reference to investigation and research conducted jointly by teachers and others. These councils’ selections are the final decisions.

This local selection process differs from the screening process in MEXT in that it is designed to reflect more input from parents and others. The selection councils include schoolteachers and academics, whose opinions carry weight, but other voices are also heard. When the Japanese Society for History Textbook Reform emerged early in this century and started a movement calling for a more nationalistic approach to the teaching of history, it therefore focused on the local selection process, seeking to drown out the voices of classroom teachers and academics by appealing to parents, local boards of education, and local assemblies.(*6)

In Closing

The Japanese textbook system emphasizes procedural transparency at the stage of screening by MEXT and input from citizens at the stage of local selection. In other words, transparent, decentralized decision-making procedures have been established in a manner befitting the system of liberal democracy set forth in Japan’s Constitution.

This system did not arise directly from the democratization process after World War II, however.(*7) In the mid-1960s, Ienaga Saburō and other textbook authors, along with publishing company workers and junior high and high school teachers, undertook a strong protest movement against the screening process conducted by the Ministry of Education (predecessor to MEXT). They argued that this screening constituted censorship, which is forbidden by the Constitution, and they filed three lawsuits. At first the courts mostly ruled against them, but in the 1990s they won a substantive victory. The court ruled that the screening itself was constitutional but that the specific demands for revisions issued by the ministry were arbitrary and illegal. In line with this court ruling, the ministry subsequently exercised restraint in its requests for revisions under the screening process.

The shift in the ministry’s posture occurred in the context of two developments. One was that Japanese society had come to view liberal democracy as a self-evident value. Even after World War II some of the bureaucrats in the ministry continued to hew to the prewar values of imperial Japan and resist the introduction of democratic thinking, but as they grew older and retired, a younger generation of civil servants educated under the postwar democratic system rose to management posts. The change of generations was also prominently visible among judges. Another development was that in the 1980s neighboring countries started to criticize the contents of Japan’s history textbooks. The administrations in power during those years were seeking to turn Japan, which had become a major economic power, into a major political power as well, and in pursuit of this goal they were stressing harmony with neighboring countries in particular. For this reason, the Japanese government took their criticism into account and revised the Textbook Examination Standards with the addition of the “Asian neighbors clause” mentioned above.

The shift toward greater transparency in the screening process and restraint by the ministry from arbitrary interference ended up making it more difficult to accept the demands from neighboring countries. At first South Korea and China believed that the Japanese government could intervene in determining the content of textbooks, just as they could with their systems of government-designated texts. They thought that if they applied pressure on Japan’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs and if this were relayed to the Ministry of Education, the latter could, through the screening process, make textbook publishers and authors incorporate the Korean and Chinese interpretations of the historical record. But this ran contrary to the liberal orientation of the Japanese government at the time, and it was a dangerous path to advocate. If it had been permitted to undertake major interventions affecting textbook contents through the screening process, there was a real possibility that the results could have been the opposite of what these neighboring countries intended: Certain Japanese politicians and groups could have ended up with the power to force history texts, which had been kept relatively liberal in content, to be revised in a nationalistic direction. The emergence of the movement led by the Japanese Society for History Textbook Reform in the mid-1990s and the fierce debate over textbooks in 2001 have clearly shown the existence of such a danger, as has the controversy over visits by Japanese prime ministers to Yasukuni Shrine (a sore point with Japan’s neighbors because the spirits of the war dead enshrined there include figures convicted as war criminals).

The new, liberal approach toward textbook screening that became established by the 1990s has proven its resiliency by coming through this political turmoil. And it seems unlikely that a movement to make major changes in the existing system and practices could gain traction in today’s Japan.

We do, however, hear voices from academia and from within the school system expressing dissatisfaction with the content of history education. People are asking, for example, whether it is appropriate to split the history of Japan and the history of other countries into separate subjects in this age of globalization. They also question the validity of a history curriculum that does little more than make students memorize dry facts. Eventually the Courses of Study will come up for their decennial revision, and it is hoped that opinions of this sort will be taken into account at that time.(*8))

(Originally written in Japanese.)

(*1) ^ More details on Japan’s textbook system can be found on the Ministry of Foreign Affairs website: “How a Textbook Becomes Part of a School Curriculum,” . The following collection of essays is also a good reference: Yang Daqing, Liu Jie, Mitani Hiroshi and Andrew Gordon, eds., Toward a History Beyond Borders: Contentious Issues in Sino-Japanese Relations (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Asia Center, 2012).

(*2) ^ Peter Duus, “War Stories” in Gi-Wook Shin and Daniel C. Sneider, eds., History Textbooks and the Wars in Asia: Divided Memories (New York: Routledge, 2011).

(*3) ^ English translation from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs website, http://www.mofa.go.jp/policy/education/textbooks/overview-3.html.

(*4) ^ Mitani Hiroshi, “Writing History Textbooks in Japan” in Gi-Wook Shin and Daniel C. Sneider, eds., History Textbooks and the Wars in Asia: Divided Memories (New York: Routledge, 2011).

(*5) ^ This system was introduced early in the 1960s along with the start of free distribution of textbooks for compulsory education, and it created the possibility of differences of opinions between the selection districts and municipal boards of education. Such a case has this year (2012) become an actual issue in the Yaeyama Islands of Okinawa Prefecture. See, for example, this editorial from the Daily Yomiuri (February 24, 2012): http://www.yomiuri.co.jp/dy/editorial/T120223005510.htm (In August 2011, the Yaeyama Textbook Selection District Council, composed of the boards of education of the city of Ishigaki and towns of Taketomi and Yonaguni, selected textbook published by Ikuhōsha and edited by the Committee to Improve Textbooks (Kyōkasho Kaizen no Kai), an organization that split from the conservative Japanese Society for History Textbook Reform, for use in junior high school civics classes from April 2012. The Taketomi Board of Education opposed this decision and independently opted to use a text published by Tokyo Shoseki.—Ed.

(*6) ^ Mitani Hiroshi, ed., Rekishi kyōkasho mondai (The History Textbook Issue) (Tokyo: Nihon Tosho Center, 2007).

(*7) ^ Ibid.

(*8) ^ The recommendation of the Science Council of Japan published on Aug 3, 2011, can be accessed here (Japanese only): Atarashii kōkō chiri/rekishi kyōiku no sōzō: gurōbaruka ni taiō shita jikūkan ninshiki no ikusei (Creating a New System for High School Geography and History Education: Fostering New Awareness in Response to Globalization

World War II China Yasukuni Shrine South Korea textbook controversy Korean Peninsula