The Shifting Landscape of Japanese Religion

Japan’s Religious Ambivalence: The Shaping and Dismantling of a National Polity

Society Culture Lifestyle- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Influences of Revealed Religions in Japan

In 1996 the religious scholar Ama Toshimaro published a book titled Nihonjin wa naze mushūkyō na no ka, which was translated into English (as Why Are the Japanese Non-Religious?) and Korean, becoming widely read internationally. In the book Ama suggests that, although the Japanese are said to be mushūkyō (nonreligious), this is because comparison is being made to “revealed” religions—those with a specific founder and a clear set of teachings. Christianity claims Jesus Christ as its founder, Buddhism has Gautama Buddha, and Islam has Muhammad. By contrast, Hinduism and Shintō have no identified founder. Folk religions have no founders either; rather, they are popular systems of belief that have evolved naturally.

Religion in Japan has been greatly influenced by revealed religions. Buddhism entered Japan in the sixth century and was the most influential religion until the mid-nineteenth century. Even today, most Japanese hold Buddhist-style funerals or are familiar with Buddhist statues. Some can distinguish between the different kinds of statues, such as Amida Buddha (Amitabha in Sanskrit), Kannon Bodhisattva (Avalokitesvara), and Jizō Bodhisattva (Ksitigarbha). The vast majority of Japanese people visit their family graves every year, in front of which they place their palms together in a Buddhist form of prayer.

Christianity has also exerted a strong cultural influence in Japan since the late nineteenth century through the establishment of missionary schools and the introduction of Western scholarship, but Christians as a religious group account for no more than about 1% of the entire population. There are some “revealed” variants of Shintō, including Tenrikyō, founded in the mid-nineteenth century by a village woman named Nakayama Miki. Many of the new Shintō sects have been influenced by Shintō-Buddhist syncretism, as Shintō, until the mid-nineteenth century, was largely inseparable from Buddhism, a fact that reveals the very powerful influence Buddhism exerted in Japanese society.

Natural Religion at the Core of Japanese Faith

Ama noted that while revealed religions have had a certain degree of influence, at the core of the Japanese people’s faith are aspects of natural religion. People worship local and family deities in the absence of highly developed doctrines. Thus the seeming nonreligious nature of the Japanese people can be said to be a manifestation of their Shintō (in the broad sense) or folk beliefs. At the heart of Japanese faith is a natural religion, which, despite the influence of later revealed religions, has not been uprooted. This is the reason many Japanese feel uncomfortable with a powerful revealed religion and conclude it is not for them. The self-applied mushūkyō label applies, then, only insofar as religion is defined narrowly (as revealed religion).

This is the gist of Ama’s argument in Why Are the Japanese Non-Religious? The book was published in 1996, the year after the subway sarin gas attack by Aum Shinrikyō. Many of the group’s members were men in their twenties, particularly undergraduate and graduate students, with specialized knowledge of computer graphics, medicine, natural science, and other areas. Were these young people lured by Aum’s teachings as an alternative to Japan’s mushūkyō religious vacuum?

Ama discounts the vacuum premise, noting the existence of an indigenous natural religion. Natural religions, certainly, are not a thing of the past. While they have been around since primitive times, many have evolved into revealed religions, scholars say, as humankind reached more exalted stage of sapience. This interpretation links the development of human civilization with the increasing sophistication of revealed religions. In Japan’s context, natural religions refer to faiths that predate the arrival of Buddhism.

Shintō can be considered a form of natural religion. Before Aum Shinrikyō’s activities began making headlines in the 1980s, animism was a popular filter through which Japanese religion was conceptualized. Although Shintō’s association with prewar nationalism gives it an aura of national exclusivism, that image changes when it is interpreted as a form of animism. The Shintō that existed before the country came under a centralized authority is known as Koshintō, or ancient Shintō; some Japanese contend that Koshintō lies at the very root of their religious sentiments, but from the perspective of a religious scholar, such notions are nothing more than a convenient, modern invention.

Confucianism as a Quasi-Religion

As I have described above, the Japanese can be characterized as being either nonreligious or practicing a form of natural religion. Despite people’s disavowal of adherence to any specific set of teachings or precepts, though, they do actively ascribe to quasi-religious practices and beliefs.

A case in point is Confucianism. The Japanese value courtesy and will show it by bowing to anyone—a custom that appears to derive largely from Confucianism. Honorifics are used, even by teenagers when talking to their seniors. The language they use when talking to their juniors is quite different, as they place importance on chōyō no jo (the Confucian concept of order between seniors and juniors, in which older people look after their juniors and younger people respect their elders). Honoring the dead is also characteristic of Confucianism. While funerals and grave-visiting customs are the domain of Buddhism, as stated earlier, they may also have been influenced by Confucianism.

Whether or not Confucianism is a religion depends on how religion is defined. But there is religiosity in the value it places on the mandate of heaven, the continuity of life from ancestor to descendant, and order imparted with sanctity through ritual. In East Asia, moreover, the word dō (or tao in Chinese, meaning the “way”) is considered to correspond to the Western-derived word shūkyō (religion). In the minds of seventeenth- and eighteenth-century Japanese, both Buddhism and Confucianism were disciplines that showed the “way.”

Solitude in Vagabond and the Modern Dō

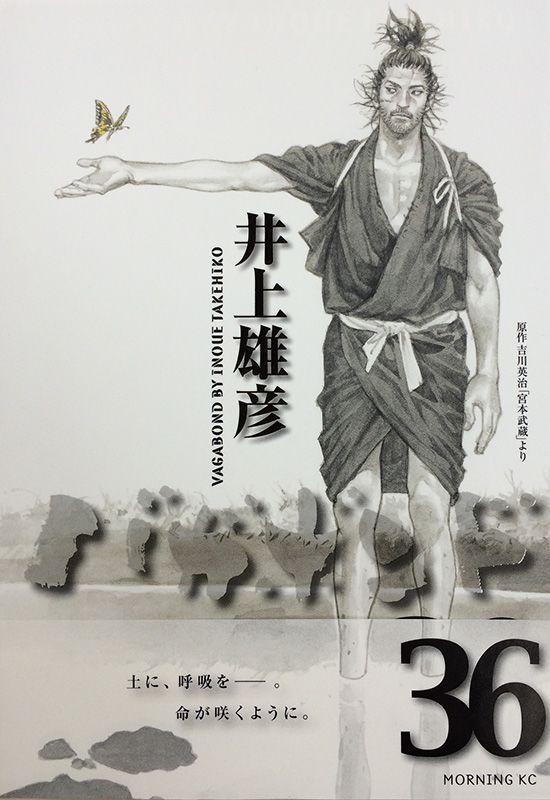

The role of Confucianism—a prime example of a quasi-religion—in society has declined since the Meiji Restoration of 1868. But there are many more examples of quasi-religion in Japan. Take the manga Vagabond, for instance. The series counted 36 volumes as of October 2013, with a total of more than 60 million copies printed in Japan since it was first serialized in a manga magazine in 1998. The protagonist is Miyamoto Musashi, a real-life samurai who lived in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Musashi was a rōnin (masterless samurai) but one of the most skilled swordsmen in history, and he also wrote a book on bushidō, the way of the warrior. The manga series is based on Miyamoto Musashi, a serial novel that Yoshikawa Eiji wrote for a newspaper in 1935. The novel became a bestseller and was adapted into film.

Volume 36 of Inoue Takehiko’s Vagabond, published by Kodansha in October 2013. © I.T. Planning, Inc.

Volume 36 of Inoue Takehiko’s Vagabond, published by Kodansha in October 2013. © I.T. Planning, Inc.

This romanticized tale of a loner who lives by the sword has struck a chord with today’s young people. Although the protagonist of Vagabond is a samurai, he has no master to serve, allowing him to live freely as he chooses. It is a life on the road, taking the swordsman around the country far away from home, where he duels with the most formidable opponents he can find and always comes out the winner. Every victory is earned at the risk of his own life, so he is always conscious of death. The protagonist struggles with the meaning of life, and he ponders why he must continue to fight. It is a worldview in which winning over others has become a goal in and of itself—and one that reverberates strongly with modern readers asking themselves similar questions.

Bushidō has become a buzzword in recent years, partly due to the 2003 US film The Last Samurai. It connotes a life in which one is prepared each day to give one’s life in combat for one’s master, so there is constant awareness of the possibility of death. People seem strongly attracted to this style of life, perhaps feeling that bushidō holds a clue to their own search for meaning in life. This is another example of how even “nonreligious” Japanese embrace religious themes, especially when framed in terms of dō.

Many of the students in the Department of Religious Studies at the University of Tokyo are also engaged in the arts, such music or theater. A great many also practice martial arts like aikidō and kyūdō (archery). Of the students I have personally met, a considerable number joined the department because they wanted to explore in greater depth the experiences they had while in high school or college through martial arts. This tendency is not limited to younger people; many seek emotional stability by learning pottery or practicing sadō (the way of tea) later in life, rather than seeking solace in lofty religious teachings. This preference for the acquisition of spiritual value through various forms of “art” or the “way,” which are more tangible and accessible, may be regarded as a feature of Japanese culture.

State Shintō Disseminated through Schools

There are thus many “quasi-religions” in Japan that are not perceived as being true religions, the most influential of which was probably State Shintō. Until the end of World War II, Japanese schools religiously followed the instructions contained in the Imperial Rescript on Education, the teachings on the fundamental spirit of education bestowed by Emperor Meiji in 1890. Elementary schools became the “shrines” where the imperial teachings were imparted, and the Japanese of this era grew up learning Shintō styles of worship. They would bow toward faraway Ise Shrine and the Imperial Palace, pay their respects at Yasukuni Shrine and Meiji Shrine, and bow their heads to the portraits of the emperor and empress and the framed Imperial Rescript on Education. This is what is known as State Shintō, and this is what was taught in Japanese schools.

Those of my parents’ generation, born in the early 1920s, remember the songs celebrating Kigensetsu(*1) on February 11 that they sung in school, and they would hum them even as adults.

The songs included lyrics depicting the reign of an unbroken line of emperors descended from the god Ninigi no Mikoto, grandson of the sun goddess Amaterasu Ōmikami. Also appearing in the lyrics is Asuka in present-day Nara Prefecture, which was the nation’s capital around the seventh century and where the imperial family established its rule.

Another song sings about primordial times, when Emperor Jinmu began his dominion as the first human emperor based on the unity of religion and the state. This emperor, shrouded in myth, is said to have ascended the throne in Kashihara, Nara Prefecture. The shrine Kashihara Jingū was erected there in 1890, the same year as the promulgation of the Imperial Rescript on Education.

State Shintō was disseminated more through schools than shrines. Not just Kigensetsu but most national holidays prior to World War II were days when the emperor conducted important Shintō rituals at the Imperial Palace. Imperial Shintō, Shrine Shintō, and school events were the primary vehicles of State Shintō rites, and children learned about the ideologies of kokutai (“national polity”) and emperor worship through the Imperial Rescript on Education, as well as in classes on such subjects as ethics and history.

The Story of State Shintō

One common misconception regarding Shintō is that it is a religion centered on shrines, the priesthood, and worshippers. This is much too narrow an understanding of Shintō. In fact, emperor worship was the main thrust of State Shintō, which was propagated not at shrines but through schools and at national festivals, which were much closer to the people of modern Japan, as well as by the media. It was a new form of Shintō that took shape in parallel with the modern nation state on the basis of the kokutai ideology developed in the Edo period (1603–1868).

Kokutai in the broad sense refers to a country’s political system. But in Japan, especially prewar Japan, it has had a more specific meaning, referring to the unbroken line of emperors descended from heavenly gods who have reigned over the people from the dawn of time. Kokutai also connotes the belief that this national polity makes Japan superior to every other nation in the world.

What place, then, does State Shintō hold in the long history of Shintō? It is difficult to pinpoint the origin of Folk Shintō, lying as it does on the same spectrum as various amorphous folk beliefs. Its beginnings may lie somewhere in the prehistoric Yayoi or Jōmon era, and some people use the word Koshintō to refer to this ancient incarnation.

The origins of Imperial Shintō, by contrast, can be determined with some degree of certainty. Its foundations were laid with the development of state rituals and legal codes modeled on Tang China between the late seventh and early eighth centuries, around the time of Emperors Tenmu and Jitō. Buddhism was the dominant religion in medieval Japan, however, and Imperial Shintō receded from popular view, as it had little bearing on people’s lives in the community. The effort to place Imperial Shintō at the center of national life through the ideas of kokutai and the unity of religion and the state gathered momentum toward the end of the Edo period, and these ideas emerged as the guiding principles of the Meiji state.

Postwar Transformation of State Shintō

From the Meiji era (1868–1912) up through World War II, the government (Ministry of Education) maintained that Shintō was not a religion but a Japanese folk custom. As such, all Japanese citizens were required to take part in State Shintō rituals at shrines and schools, even if they were Buddhists or Christians. Shintō sects upholding teachings distinct from those of Imperial Shintō were called Sect Shintō, though, and treated as religions.

The General Headquarters (GHQ) of the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers, which governed Japan after World War II, believed that the roots of Japan’s militarism and ultranationalism were to be found in the nature of religion in Japan, particularly, the lack of separation of religion and the state. The GHQ quickly took steps to remove what it felt to be the adverse religious and ideological influences that had led the Japanese into a reckless war. On December 15, 1945, it issued the so-called Shintō Directive, and on January 1, 1946, Emperor Shōwa made the “humanity declaration” denying the divinity of the emperor in his New Year’s statement.

These moves essentially dismantled the State Shintō machinery, but Imperial Shintō remained largely intact even after the war. Active efforts have been made to reinforce the ties between the imperial family and Shrine Shintō and to enhance Shintō’s national role. In that sense, State Shintō has not died out completely even after the war.

State Shintō was originally underpinned by grassroots movements associated with emperor worship and was supported by the Jinja Honchō (Association of Shintō Shrines), which became a private entity after the war. Although much weaker today, State Shintō continues to attract many devotees with its message of Japan’s divinity, owing to the freedom of religion that Japan enjoys. It goes without saying, though, that its activities must not oppress the freedoms of people with different religious and ideological beliefs.

Article 20 of the Constitution

Given Japan’s prewar experience, there may be fears that the Japanese people would again be forced to take part in State Shintō rituals and lose their freedom of thought and religion, but this is prohibited by Article 20 of the Constitution of Japan stipulating the freedom of religion. Section 1 reads, “Freedom of religion is guaranteed to all. No religious organization shall receive any privileges from the State, nor exercise any political authority.” Sections 2 and 3 continue, “No person shall be compelled to take part in any religious act, celebration, rite, or practice,” and, “The State and its organs shall refrain from religious education or any other religious activity.” In short, the Constitution makes clear that no one must be forced to submit to State Shintō, nor must the state grant a special status to Shintō.

Prime Minister Abe Shinzō’s visit to Yasukuni Shrine on December 26, 2013, has brought the significance of this shrine under renewed scrutiny. If Yasukuni were ever to be made into an official ceremonial facility of the state, it would imply a regression toward the prewar regime that drove the Japanese people to religious worship of the emperor. Article 20 has thus played an important role in keeping State Shintō in check.

Most Japanese have little involvement with religion today to the point of being regarded as nonreligious. But as State Shintō illustrates, religion does have significant implications for society and the state, even in Japan. This is a point that should not be overlooked.

(Title photo: People shopping at Yasaka Shrine in Kyoto for wooden plaques on which to write their wishes and decorative arrows to ward off misfortune. Photo by R-CREATION Co., Ltd./Aflo.)

(*1) ^ Established in 1872, based on the belief that February 11 is the day when Emperor Jinmu ascended the throne, as described in the Nihon shoki (Chronicle of Japan). Kigensetsu was abolished in 1948, but the day has been a holiday known as National Foundation Day since 1966.

Buddhism Yasukuni Shrine Shintō Christianity religion State Shintō Kokutai Article 20