The Many Faces of Japan-China Relations

Tackling China’s Diabetes Problem

Society- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

China now has the world’s largest diabetic population. In 2010, the International Diabetes Federation estimated that 92.4 million Chinese people were suffering from the condition. Lifestyle changes and other factors have triggered a surge in the number of diabetes patients.

I was involved in the proposals and planning for the Japanese-Style Diabetes Treatment Services Project, aimed at tackling this growing problem, which was implemented in Shanghai in fiscal 2011 (year starting April 2011) and Hangzhou in fiscal 2012. I also participated in the project as a physician. In this project, part of the Internationalization of Medical Services Initiative organized by Japan’s Ministry of Economy, Trade, and Industry, a medical team consisting of Japanese doctors, nurses, dietitians, pharmacists, and other staff worked in a consortium with Japanese corporations to examine and treat patients on-site in Chinese hospitals.

The impetus for this undertaking was an invitation I received to give a speech in China in 2010, at which time I also visited some medical facilities. China had been looking to the West in its thinking about diabetes treatment. However, one of the notable characteristics of diabetes is the great disparity in how it affects people of different races. I think the reason I was invited was because people in China had realized this and started to turn their eyes to Japan, the country with the most advanced medical technology in Asia.

I was taken aback by how treatment was handled in China. In Japan, the basis for diabetes treatment is managing diet, exercise, and lifestyles; doctors only resort to medication and insulin treatment if these initial approaches are unsuccessful in lowering blood sugar. The standard is patient-centered empowerment through team treatment, with nurses, dietitians, pharmacists, and physicians providing appropriate guidance and instruction at each stage and drawing out and maintaining patients’ motivation. But in China, such thinking is almost nonexistent. Doctors dictate treatment relying primarily on medication, and the amounts prescribed are similar to those given to patients in Europe and North America—two to four times the doses prescribed in Japan. As a result, patients often end up experiencing hypoglycemia (low blood sugar); this has eroded their trust in their physicians.

There are also many problems with the facilities themselves. Even China’s top hospitals do not take acoustics into account in their design, and they are extremely noisy with, for example, examination rooms where four doctors at a row of desks simultaneously examine four patients.

When I first learned all this, I felt keenly that I wanted not just to give a speech but also to introduce and spread the use of Japanese know-how and techniques in helping China’s many diabetes patients and genuinely advance medical cooperation between the two countries. Coincidentally, just then METI began inviting applications for participants in its initiative to export Japan’s high-quality medical treatment on a comprehensive basis. It was a perfect opportunity, and I seized it.

Surprising Reactions from Patients

I was sent to Shanghai for the first project in October 2011. We established a Japanese-style diabetes clinic at a city hospital and provided free services for Chinese diabetes patients, including checkups by physicians, classes conducted by nurses, and advice on diet from dietitians. The benefits were obvious, with patients showing improvements in all areas, including weight, blood sugar, blood pressure, and fats. And the improvements were more pronounced among patients whose visits to the clinic were more frequent.

However, we had not anticipated the reactions we would get from patients. After I checked them and they finished their rounds of seeing the nurse and the dietitian, many made a point of coming back to see me: “So many people have done so many things just for me. Thank you very much.” They bowed as they thanked me with words like these. And they all left with a smile on their face. Then there was the time I was taken aback when a patient suddenly burst into tears after emotionally describing his symptoms. When I asked him why, he replied, “Nobody has ever listened this kindly when I’ve talked about myself before.” Some Chinese medical staff members, startled and moved by the patients’ reactions, told me they would like to be part of the team creating a cycle of positive feedback through this kind of trust relationship.

In surveys too, patients showed an extremely high level of satisfaction with our Japanese methods. This, along with the alleviation of symptoms, reconfirmed my belief in the concept of team medicine and the importance of this approach.

Senkaku Flare-Up an Unexpected Obstacle

Although the project had got off to a flying start, it met an unexpected obstacle in 2012 in the form of anti-Japanese movements and demonstrations in China sparked by the Senkaku Islands dispute. Plans to more thoroughly implement the project over a wider area that year by making it a paid service in Shanghai and expanding to Guangzhou had to be shelved after both hospitals hastily withdrew. This must have been a tough decision.

However, despite the wave of anti-Japanese sentiment, we received a new invitation from Hangzhou urging us to implement our project there. To be honest, we felt somewhat hesitant. Even if the hospital management wanted us to come, we feared that the deterioration of relations between Japan and China might affect patients’ attitudes. But in the end the other project members and I decided that we would go and, while taking careful note of the potential problems, aim to provide an even higher level of service than we had in our first year.

When we actually went to Hangzhou, we discovered that our worries had been needless. Just as in Shanghai, the patients were satisfied with our Japanese-style treatment and thanked us sincerely. The people at the hospital came to appreciate the value of team medicine and invited us to work there again. And after we returned home, the Hangzhou hospital decided on a policy of asking interested candidates in all job types to apply for training in Japan. Not one of the Chinese patients or medical professionals I encountered considered the quarrel between our countries when we met or let it affect their attitude toward me.

Personal Connections

The main thing I learned in two years on the China project was that if you give your all when working in a medical setting, this will convey itself to the people around you and build mutual trust. By respecting and acknowledging differences in culture, customs, and ways of thinking while drawing on each other’s strengths, we can achieve a closer and more mutually beneficial relationship. I believe that value of this win-win approach is not limited to dealings with Chinese or other Asian counterparts but is in fact the essence of international exchange.

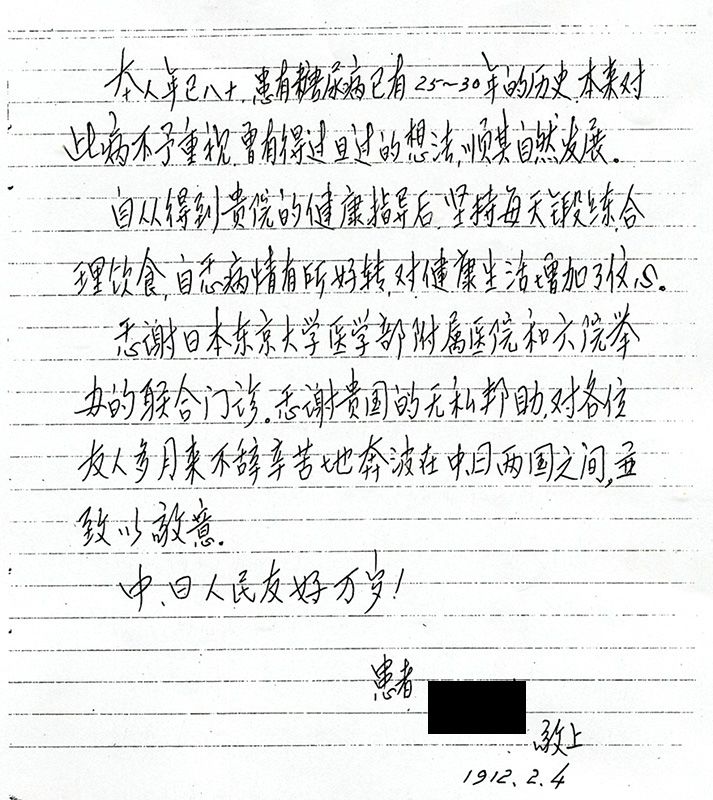

One 80-year-old outpatient who visited our clinic in Shanghai five times gave me a letter when he received his final checkup. Until he came to us he had been told “Don’t eat this. Don’t eat that,” and apparently he had fallen into a state of semidepression. We told him that so long as he paid attention to calories and balancing his diet, it was fine to eat the things he liked. His symptoms improved, and he gained a more positive approach to managing his diabetes. When I read his letter, I felt a renewed confidence in the ability of our approach not just to alleviate the symptoms of disease but also to change people’s lives.

Letter from an 80-Year-Old Patient

Letter from an 80-Year-Old Patient

I am 80 years old. I have had diabetes for 30 years. At first, I did not think it was much of a problem and left it to take its natural course. But from everything all of you have taught me, I have learned to maintain an appropriate daily diet and exercise routine, I have felt an improvement in my symptoms, and I have gained the confidence to live a healthy lifestyle. I am grateful for the cooperation between Japan and China in treating patients and I have great respect for the way you all have traveled repeatedly between the two countries for months without showing any fatigue.

Long live friendship between the Chinese and Japanese peoples!

Sincerely,

[Patient’s Name]

February 6, 2012

A Dream of Furthering Sino-Japanese Cooperation

I myself am half Chinese through my father and half Japanese through my mother, and I lived in China until I was 16. With that background, it has been my dream of many years and a personal mission to further Sino-Japanese medical cooperation based on the knowledge and techniques I have learned in Japan. As Japan’s population declines, the number of people receiving Japanese-style treatment will also drop. Exporting this treatment is a meaningful undertaking: Not only is it a way of contributing to the health of people in other countries, but it will help us maintain and develop Japan’s medical technology, which represents a precious resource, an asset to be shared by humanity as a whole.

Unfortunately, METI was obliged to cancel the China project after two years, but as there are still a lot of hospitals that would like us to continue, I plan to work on starting up again in some form or other. If possible, I would like to establish a network for prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of diabetes in China. I also want to create a base for cooperation in education and research as well as clinical treatment. And I would like to build a structure for working together in all areas where Japan’s high-level medical technology can make a difference. That is my goal.

(Originally published in Japanese on August 15, 2014. Based on an interview edited by Minamiyama Takeshi. Photographs by Kodera Kei.)

China University of Tokyo Shanghai medicine diabetes UTokyo Hangzhou