Japan’s Welfare Policies at the Crossroads

Policy Fixes Needed for Japan’s Elderly Women

Society Culture- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Elderly Women’s Needs Ignored

In examining the phenomenon of aging in Japan, let me start with some numbers. Japan’s average life expectancy in 2013 was 80.21 years for men and 86.61 years for women—marking the first time that male life expectancy exceeded 80 years.(*1) Japanese women could expect to live six-and-a-half years longer than men, though, and have long been at the top of the world’s longevity rankings. This means that the older one gets, the higher the share of women in the population.

The 65-and-over population is 56.9% female. The share rises to 61.4% for those aged 75 or over—when all residents switch to the Latter-Stage Elderly Healthcare System—and to 70.2% for people aged 85 or over. This means that for this age set, women outnumber men 2.3 to 1.(*2) There were 58,000 centenarians in Japan in 2014, 87.1% of whom were women.(*3)

The old-age population, in short, is predominantly female. One would assume from this that policies for Japan’s eldest citizens would focus on the needs of women, but this is far from the case. In fact, policymakers have all but ignored women’s needs at key junctures in their lives in areas like employment and social security. The first step in rectifying these policy gaps, then, would be to ensure that women appear on the policy radar screen by raising their visibility. The lack of visibility, though, is not a problem for women alone; senior men and women alike have surprisingly failed to elect their cohorts to positions of policymaking influence.

Underrepresented

Following the December 2014 general election, the share of House of Representatives members aged 65 or over was 16.8%, and that of those aged 75 or over was just 1.3%. These percentages are much lower than the corresponding ratios for the general population, where over 25% are aged 65 or older and 12.5% are aged 75 or older.

This means that the Latter-Stage Elderly Healthcare System for people aged 75 or older, introduced in April 2008, was drafted, discussed, and adopted by bureaucrats in their thirties, forties, or fifties and by under-70 politicians and policy council members—without any direct input from anyone for whom the policy was actually intended.

Such lack of representation is also prevalent in the country’s dementia policy. Participants at the Global Dementia Legacy Event Japan, held in November 2014 in Tokyo, expressed the concern that they had no voice at all in shaping the measures governing their lives. In January 2015, therefore, the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare announced a New Orange Plan, a strategy to meet the growing dementia challenges that explicitly calls for greater input from dementia patients and their families.

Japan’s elderly may be the target of numerous policies, but they do not have the final say on the content of those measures. Among the small number of Diet members over the age of 75, not one is a woman. The share of female legislators is just 9.5% in the House of Representatives and 15.7% in the House of Councillors (as of December 2014). The Global Gender Gap Report issued by the World Economic Forum ranks Japan 104th among the 142 countries surveyed in terms of gender equality.

Old-Age Poverty

Japan’s elderly women are thus doubly shut out of the decision-making process, first for being a woman and second for being old. Throughout Japan’s modern history, policies concerning women’s education, family relations, social role (such as employment), social security, and childbirth (including pregnancy and abortion) were all decided by men. Given women’s lack of representation in key social and political decision-making forums, it is no wonder that few are prosperously engaged in their golden years.

Women in old age are invariably at a disadvantage. They not only face financial difficulties but are also burdened by expectations that they serve as caregivers. These women, trapped in poverty, though, have long sustained Japan’s growth and development.

In The Second Sex, French writer and feminist activist Simone de Beauvoir noted, “One is not born, but rather becomes, a woman.” In Japan, one might say that a woman is not born poor but becomes so as she grows old.

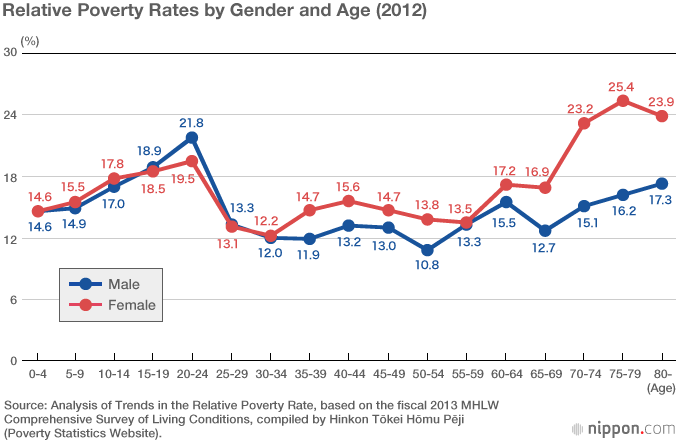

Statistics bear this out. The relative poverty rate, which refers to the percentage of people whose disposable income falls below the 50% median, is higher for women in all age groups, except briefly during the late teens and twenties. The income gaps widen as they age, particularly after reaching 65; by the time they are 80, 23.9% of women are in relative poverty, some 7 points higher than the 17.3% of men.(*4)

The disparity is especially pronounced for those living alone; while 29.3% of men aged 65 or older were in relative poverty, the figure for women was 44.6%.(*5) The respective percentages living alone were 11.1% for men and 20.3% for women. The share earning less than ¥1.2 million annually was 23.7%—nearly one in four—for such women, and the figure rose to 32.5% for those who were divorced.(*6)

Disguised Housewives

One reason for the income inequality is that women were long discouraged from becoming breadwinners. Girls were raised to become brides, and their chief fears were being “left over” (unwed) and “sent back” (divorced). Traditionally, women joined the labor force only to supplement the household income or during the years between graduation and marriage. Until the Equal Employment Opportunity Act was enacted in 1985, not a few workplaces had very early retirement ages for female employees or obliged women to leave the work force when they married or had children.

The institutionalization of the income-earning husband and full-time housewife was reinforced during Japan’s high-growth years by the country’s corporate giants. Home economics was a free elective in the immediate postwar years but became a compulsory course for all high school girls to groom them into becoming full-time homemakers.

Forces for change began encroaching on Japan’s shores following the 1975 World Conference of the International Women’s Year, organized by the United Nations, and during the ensuing United Nations Decade for Women. In 1985 the Japanese government announced pension reforms under which full-time housewives earning less than ¥1.3 million a year would be entitled to benefits as Category 3 beneficiaries, even if they had not been paying into the national pension scheme individually. While this meant that divorced women would still be entitled to pensions, it also discouraged homemakers from earning more than ¥1.3 million. The reforms thus resulted in keeping the wages of married women low and became a big drain on fiscal resources.

Three Hurdles

Women thus face three hurdles in pursuing a career during their lifetime. The first is childbirth; even today, some three-fifths of all working women leave the work force to give birth. The second is being forced to move for family reasons, such as accompanying a husband who has been transferred. And the third is the need to care for aged parents or other relatives. The average length of employment for women is 9.3 years, which, on the surface, does not appear much lower than the 13.5 years for men.(*7) But this does not consider the fact that many women are employed in part-time and other nonregular formats, which often do not come with social security benefits. Tellingly, the average benefits under the employees’ pension plan in fiscal 2013 were ¥183,155 for men and just ¥109,314 for women.(*8) Given the need to curtail working hours to look after family members, women have fewer opportunities for career advancement leading to higher paying positions.

The low wages in the nursing care industry, said to be around 60% of other sectors, might be seen as an extension of these realities. While the industry itself is growing due to ballooning demand, there appears to be a lingering categorization of care-giving services as something that had traditionally been provided free of charge by female members of the family. And there is now increasing pressure from health administrators for healthcare and nursing care to be provided by the community or in the home, despite the changes in Japan’s family structure. What is really needed today is a fundamental rethinking of the value of institutionalized care as an essential component of contemporary life and efforts to improve working conditions.

Without such efforts, Japan could, in just another decade or two, tragically tumble into a country of “lonely deaths,” a society where the elderly die alone without anyone to look after them.

(Originally published in Japanese on April 6, 2015. Banner photo © Jiji.)

(*1) ^ Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare, “Abridged Life Tables for Japan 2013.”

(*2) ^ Population estimates as of March 1, 2015, Statistics Bureau, Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications.

(*3) ^ According to Basic Resident Register data of the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare, as of September 1, 2014.

(*4) ^ Abe Aya, 2014, Trends in the Relative Poverty Rate for 2006, 2009, and 2012 (Hinkon Tōkei Hōmu Pēji).

(*5) ^ See supra note 4.

(*6) ^ Cabinet Office, “Kōrei danjo no jiritsu shita seikatsu ni kansuru chōsa kekka” (Results of a Survey on Self-Reliant Living Among Old-Age Males and Females). Men and women aged 55 to 74 were surveyed.

(*7) ^ Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare, Basic Survey on Wage Structure, 2014.

(*8) ^ Pension Bureau, Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare, Overview of Employees’ Pension Insurance and National Pension, 2013. The figures are the average monthly benefits provided to beneficiaries (65 and older) under the employees’ pension scheme.

elderly women dementia poverty longevity income gaps housewives national pension