Reshaping the Japanese Workplace: Can “Work-Style Reform” Succeed?

Japan’s New Labor Laws and the Need to Shift from a Culture of Excessive Working Hours

Work Society Economy- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

For decades, excessive working hours have been one of the hallmarks of Japanese society. Despite repeated calls for reforms to move away from this culture and improve the way Japanese people work, the reality remains unchanged: Japan still has some of the longest working hours among developed countries. Prime Minister Abe Shinzō has made work-style reforms one of the key objectives of the current session of the Diet. But will the proposed new legislation succeed in bringing real change to Japanese working habits? In this article, I want to look at recent moves to reform Japan’s working culture and examine some of the outstanding problems that remain, focusing on five key issues: upper limits on overtime, use of paid leave, achieving more diverse and flexible working styles, promoting side business, and employee training.

New Caps on Overtime: A Step-by-Step Approach

First, regarding the upper limits on overtime, the labor standards law was recently amended to include new regulations that will supposedly limit the amount of overtime to less than 100 hours in any one month, and no more than 720 hours in total over the course of a year. This amounts to 60 hours a month, or roughly 3 hours of overtime per working day.

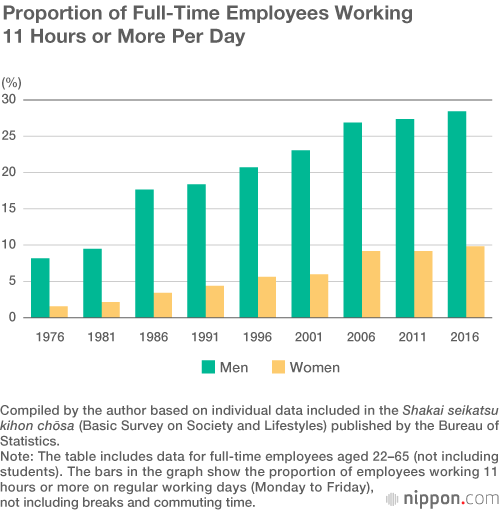

As shown in the table below, Japanese people are steadily getting busier on weekdays. This is based on my calculations using individual data from a time-use survey carried out regularly by the government’s Bureau of Statistics. In 2016, around one third of men and 10 percent of women in full-time jobs were working 11 hours a day or more. This represents actual working hours, and does not include commuting time or breaks. If we take regular full-time hours to be eight hours a day, these figures mean that many people are working for three hours or more of overtime on average every day.

The recently introduced caps on overtime have been criticized in some quarters for setting the limits too high: 100 hours of overtime a month could still lead to “overwork” in some cases, critics claim. But there is also a risk that the legislative system would lose its effectiveness if an attempt were made to impose overambitious standards that are totally detached from the current reality.

The priority should be to start with caps that can realistically be implemented, and make sure that they are followed. Ideally, further revisions would then be introduced at an early stage to bring down the monthly limits further and gradually reduce the total amount of annual working hours.

In making these revisions, it is important to consider ways of simplifying the rules. The recent caps on overtime were set after consideration of a wide range of diverse opinions; as a result, the rules are quite complicated. A system of rules that is easy to understand would also make it easier for citizens to keep an eye on companies that may be breaking the law.

Forcing Workers to Take Time Off

Second, the recent revisions to the Labor Standards Act include provisions designed to encourage employees to use more of their annual paid leave. For employees who receive an allowance of ten days or more of paid leave a year, five of these days will now have to be taken within a designated period. This revision has attracted less attention than the limits on overtime, but is also an important step toward changing work-styles in Japan.

At present, Japanese workers take an average of around eight days of paid leave per year. This is less than half of what they are theoretically entitled to. Somewhere between 10 and 20 percent of workers do not take a single day off in a whole year. One reason why these figures are so low is that in the past the decision when to take time off lay entirely with employees.

This meant that employees could not use their annual leave entitlements unless they specifically asked permission do so. This often created an atmosphere in workplaces in which employees felt reluctant to ask for leave if their colleagues and superiors were not taking days off. This recent change places an obligation on employers to “force” employees to use at least five days of leave a year, whether they like it or not. This is regarded as a first step, and it is hoped that the take-up rate for annual leave will further increase in the future.

Why Working Hours Increase During a Recession

Regarding the need to support more diverse and flexible work-styles, a new work style system has been introduced for high-level professionals in specific specialized fields. The system applies to workers in certain clearly defined fields requiring a high level of specialized knowledge, who earn at least ¥10.75 million a year. With the consent of the individual employee and following approval by a committee, these workers may be exempted from restrictions on working hours, holidays, and additional pay for late-night work, while ensuring that measures remain in place to protect employee health.

It seems that there is a strong belief among employers that performance-based pay rather than paying by the number of hours worked will improve productivity by providing an incentive for workers to produce better results. On the other hand, many workers are opposed to the new system, claiming that it will lead to overwork.

Do working hours change when a worker becomes exempted from overtime regulations? In a 2012 study I carried out together with Professor Yamamoto Isamu of Keiō University, we used panel data that tracked the same individual over a prolonged period. We analyzed the impact on working hours when a worker who was previously subject to working hour regulations moved to the current discretionary labor system or promoted to managers or supervisors who are not to subject to time regulation.

Using econometric methods, we matched workers as much as possible with two groups: those for whom overtime regulations applied and those not subject to strict time supervision. Our results revealed a statistically insignificant difference between the average working hours for the two groups. But when we limited our focus to the period of global financial crisis in 2008, we found that the working hours of the exempted group became longer than those subject to overtime regulations.

Our interpretation of this data was that when the economy slows down, companies that want to save overtime payments tend to assign work to employees who are not subject to overtime regulations . When the economy was dominated by secondary industry, production tended to slow down and working hours got shorter when the economy was doing badly. But today, when the tertiary sector dominates the economy, there is a tendency for the working hours of incumbent employees to get longer during recessions, as clearly shown by a 2015 research paper I wrote with Genda Yuji and Ohta Souichi.

Performance-Based Pay: Proper Incentives Are the Key

In today’s world, there is a lot of work that needs to be done even during an economic downturn, and there is a tendency for firms to assign jobs to a limited number of exempted workers during a slump. If more relaxed monitoring of hours is to be considered in the future, due care should be taken to consider carefully how widely these new standards should be applied.

As one of a range of diverse options, a work-style that allows greater freedom and does not restrict employees to a single workplace or particular hours certainly has the advantage of improving workers’ welfare. I do not deny the benefits that a greater choice of working styles can bring. But it is important to note when introducing these more flexible, apparently freer working styles, that setting up incentives by employers may result in productivity falling rather than improving, if it is not done correctly.

Extrinsic motivations from performance-based pay that evaluates results rather than process can function well in jobs where the quality and volume of work can be easily observed, and in which using the same methods will predictably produce the same results. But studies in psychology and behavioral economics suggest that in the case of highly skilled and unpredictable jobs, the same approach can often lead to results that are the opposite of those intended. For workers in professions that require creativity and novelty, it is essential to provide an environment that tolerates failure. In these cases, intrinsic incentives are essential.

The Danger of Encouraging Work on the Side

The fourth point concerns promotion of side business. As part of the recent work-style reforms, the Japanese government is encouraging people to earn supplementary income. In the past, many Japanese firms prohibited workers to take secondary jobs, but, with “cloud workers” increasing around the world, it has become difficult to continue the practice. But as the governor of the Bank of Japan said in a press conference in June 2018, “the deflationary mindset that presided from 1998 to 2013 still remains.” Despite the severe labor shortage in Japan as the effects of a declining population combine with a recovering economy, upward rigidity in wages still remains.

But encouraging secondary work while wages remain stagnant is risky for two reasons. First, it could easily discourage efforts to correct the culture of long working hours. Second, labor supply increase caused by more people taking secondary jobs might also act as further downward pressure on wages. Implementing policies in the wrong order can lead to unexpected consequences. Encouraging secondary work while the new provisions for correcting the culture of long working hours are not fully in place is particularly risky. It is vital to be careful about the order in which these two new policies are put into effect.

Improving Productivity: The Need to Reexamine Employee Training

Lastly, I would like to add a few words about the close connection that exists between work-style reforms and employee training. In the past, many Japanese companies traditionally allowed young employees to learn by trial and error, and were happy to regard long and not necessarily productive hours as a medium- to long-term investment. Companies generally developed employees' human capital through long-term education and training .

Given the recent workplace reforms, many firms encourage employees, particularly young ones, not to work overtime and leave the office early. These young people, who are being sent home “early” before they have received full training and while their work performance is still only modest, will make up the most important part of the workforce in another decade or so.

Using data from the time use survey already quoted above, in 2016 less than 5 percent of Japanese full-time workers used 15 minutes a day or more on self-improvement or skills enhancement. This shows just how little time people are investing in improving their skills and acquiring new ones.

With the work-style reform, it has become more difficult than it used to be to invest a lot of time in on-the-job training. This makes it essential to consider the impact that work-style reforms might have on Japanese productivity in the future. We need to fundamentally reassess the way in which we carry out workforce education and training.

“We should make steady efforts to reduce working hours, with the aim of bringing them below the current levels in the United States and Britain as soon as possible.” This phrase does not come from any strategy unveiled as part of the current government-sponsored attempts to reform workstyles in Japan. In fact, it comes from the Maekawa Commission Report on structural reforms commissioned by the government in 1987. It is now 30 years since this plan was released, but, as I said at the outset, Japanese work styles remain unchanged.

With a population steadily in decline, the Japanese labor market can no longer afford to tread water if it is serious about securing an adequate workforce and achieving economic growth. One of the pressing tasks ahead of us as a society is to plan for the coming shift from a uniform, one-size-fits-all society that takes ultralong working hours for granted, to one that is tolerant and accepting of a wider diversity of working styles and allows people to work according to their own preferences and circumstances, including the need to look after children, care for elderly relatives, or take care of their own health issues.

References cited

Genda, Yuji, Sachiko Kuroda and Souichi Ohta, “Does Downsizing Take a Toll on Retained Staff? An Analysis of Increased Working Hours in the Early 2000s in Japan,” Journal of the Japanese and International Economies, 36, 2015, pp.1-24.

Kuroda, Sachiko and Isamu Yamamoto, “Impact of overtime regulations on wages and work hours,” Journal of the Japanese and International Economies, 26(2), 2012, pp.249-262.

(Originally published in Japanese on July 6, 2018. Banner photo: A woman holds a banner reading “Tadabataraki sasenaide” (Don’t make people work for nothing) at a march to demonstrate against the government’s workstyle reforms after the traditional May Day gathering National Confederation of Trade Unions. May 1, 2018, Yoyogi Park, Tokyo. © Jiji.)