Race Relations and the Battle for America’s Soul

Politics Society- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Racial tensions have spiked in the United States against the backdrop of a raging pandemic. At the center of this outbreak of racial strife are protests against police brutality toward African American citizens, a phenomenon with deep historical roots in American society. The immediate impetus for the protests was the killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis on May 25 this year. Video footage of the incident, in which a police officer knelt on Floyd’s neck until he lost consciousness—ignoring the latter’s repeated protests of “I can’t breathe”— went viral on social media, triggering nationwide demonstrations under the slogan Black Lives Matter. In several urban areas, the National Guard was called in to respond to outbreaks of rioting and looting.

With the November presidential election in the offing, President Donald Trump, much like Richard Nixon in 1968, sought to capitalize on the situation by setting himself up as the “law and order” candidate who would support the police and protect the public from rioters and looters. In this way, he seized on the Black Lives Matter Movement as a way to mobilize his core supporters: white blue-collar workers, right-wing Christian evangelists, and white supremacists.

Two Strains of Americanism

BLM has gathered momentum rapidly in recent months, metamorphosing into a global movement against racial discrimination. But it actually emerged during the administration of Barack Obama, the first African American US president. Obama’s 2012 election, initially hailed as the harbinger of a post-racial society, is now thought to have triggered the resurgence of white nationalism, particularly among the economically disaffected. How does one account for such an outcome?

In her acclaimed 2016 book Strangers in Their Own Land and Mourning on the American Right, American sociologist Arlie Russell Hochschild uses rigorous ethnographic methodology to illuminate the basic worldview underlying the rightwing populism that gained traction in the wake of Obama’s election, including its virulent opposition to taxes and federal regulation, anti-elitism, anti-intellectualism, the rejection of science, and white nationalism.

According to Hochschild, the Tea Party supporters in the economically depressed area of Louisiana where she conducted her study have embraced a historical narrative in which the federal government has consistently sacrificed the interests of white people in its eagerness to reverse discrimination against African Americans and other minorities. This conviction, she argues, is the common thread connecting the anti-government, populist, and white nationalist views of her subjects.

The election of President Obama, viewed as the culmination of decades of preferential treatment of African Americans by the federal government, fueled a major backlash among this and similar sectors of the population, which manifested itself in a rising tide of violence against African Americans. Black Lives Matter began in July 2013 in response to the acquittal of George Zimmerman, a member of a community watch group, in the February 2012 shooting death of an unarmed African American teenager, Trayvon Martin, in Sanford, Florida. The movement gained momentum after Trump’s election, as acts of anti-black violence escalated around the country.

Turning Point in Charlottesville

In August 2017, about seven months after Trump’s inauguration, members of neo-Confederate, neo-Nazi, and white supremacist groups including the Ku Klux Klan gathered in Charlottesville, Virginia, to oppose the removal of a statue of Confederate General Robert E. Lee. The protesters clashed with counter-demonstrators, one of whom was killed. In several important respects, the incident marked a major social and political turning point for the United States.

To begin with, the event highlighted historical divisions that time has failed to heal. It threw into relief sharply differing views regarding the Civil War, which ended more than 150 years ago, and highlighted lingering prejudices and injustices that have their roots in the institution of slavery. The achievements of the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s had fostered a belief in the inevitability of social progress toward racial equality and harmony; the incident in Charlottesville revealed the naivete of that belief.

Second, Charlottesville heralded the advent of an era in which fringe groups disavowed by both national parties for their racist and Nazi ideology need no longer hide in the shadows. It demonstrated that organizations that actively defend and promote racism continue to draw substantial support among certain sectors of society even in this age of global multiculturalism.

The third indication that the United States had reached a turning point was President Trump’s unwillingness to denounce the white supremacists and neo-Nazis who gathered in Charlottesville, even after he learned of the tragedy that had occurred there. Since the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which prohibits discrimination on the basis of race, color, religion, sex, or national origin, the federal government has played a pivotal role in the protection of minority rights, including the prosecution of hate crimes. Trump’s tepid response to the violence in Charlottesville sent a message that his government could not be counted on to perform that role.

In the three years since Charlottesville, racial tensions have clearly intensified in the United States. We can now say with a degree of confidence that the tools and systems put in place by the Civil Rights Act were insufficient to the task of overcoming the racism so deeply rooted in American society.

Two Strains of Americanism

In his 2001 book American Crucible: Race and Nation in the Twentieth Century, the social and political historian Gary Gerstle examines the conflicting ideologies of “civic nationalism” and “racial nationalism” that have existed side by side since the founding of the republic. Gerstle defines civic nationalism as a view of America as a collection of individuals—created equal and endowed with the “inalienable rights” set forth in the Declaration of Independence—who are bound by shared political beliefs centering on such universal values as freedom and equality. Racial nationalism views the nation in ethnic terms, as a people bound together by “common blood, skin color, and an inherited fitness for self-government.” The history of American nationalism can be seen as an ongoing tug-of-war between these two conflicting ideologies, as one side gains temporary ascendancy, only to retreat before a powerful backlash by the other.

The Civil War was an early and pivotal episode in this struggle. Through the painful reunification of the rebellious Confederate states into the Union, the ideals of civic nationalism written into the US Constitution temporarily triumphed over the racial nationalism of the South, founded on the institution of slavery. But once the federal government agreed to withdraw its troops and supervision, the Southern states passed the Jim Crow laws, which institutionalized racial segregation, discrimination, and disenfranchisement.

It was not until the mid-1950s that widespread organized resistance by African Americans began to challenge Jim Crow. In the South, police and white vigilantes responded to the civil rights movement with brutal acts of violence (frequently in the name of “law and order”). But with the help of courageous and inspiring leaders like Martin Luther King, Jr., the groundswell of nonviolent protests ultimately forced the federal government to take action. In 1964, more than a century after the end of the Civil War, the South’s system of racial segregation was legally abolished.

Progress and Reaction

But genuine equality proved difficult to attain. Since the end of World War I, vast numbers of African Americans had been migrating from the rural South to the industrial North in search of freedom and opportunity. In the cities, prejudice and resentment over the influx of cheap labor fueled a Northern brand of segregation. Even after the federal government began actively promoting the integration of schools, workplaces, and public facilities, segregation and inequality remained facts of life in the North. African Americans were effectively barred from many professions and faced rampant discrimination in employment, housing, and other areas.

In the late 1960s, against the backdrop of the Vietnam War, the frustration of young black ghetto-dwellers erupted in a series of urban race riots, exacerbated by police brutality and abuse of authority. Then in the 1970s, amid the economic strains of rising inflation and high unemployment, anti-black sentiment grew among white workers who saw themselves as victims of affirmative action and other federally mandated programs designed to counter racial discrimination.

In 1992, racial tension exploded in the city of Los Angeles. The acquittal of four LA police officers for the use of excessive force in the videotaped arrest and beating of Rodney King ignited several days of rioting in the city. By the time the unrest subsided, more than 50 people had died, about 1,700 had been injured, and roughly 6,000 had been arrested.

No End in Sight

As such events indicate, the passage of the Civil Rights Act did not signify the final victory of civil nationalism. To the contrary, the programs and policies instituted under the law quickly triggered a backlash by the forces of racial nationalism.

The pattern has continued into the current millennium. The election of Barack Obama—an African American and a true believer in the United States as a beacon of such universal principles as equality and democracy—provoked a backlash that opened the way for the election of Donald Trump, a man who tacitly countenances white nationalism.

The defeat of Donald Trump in the coming 2020 presidential election may or may not signal another swing of the pendulum. But viewed in a larger historical context, the conflict between these two mutually inimical strains of Americanism seems destined to continue.

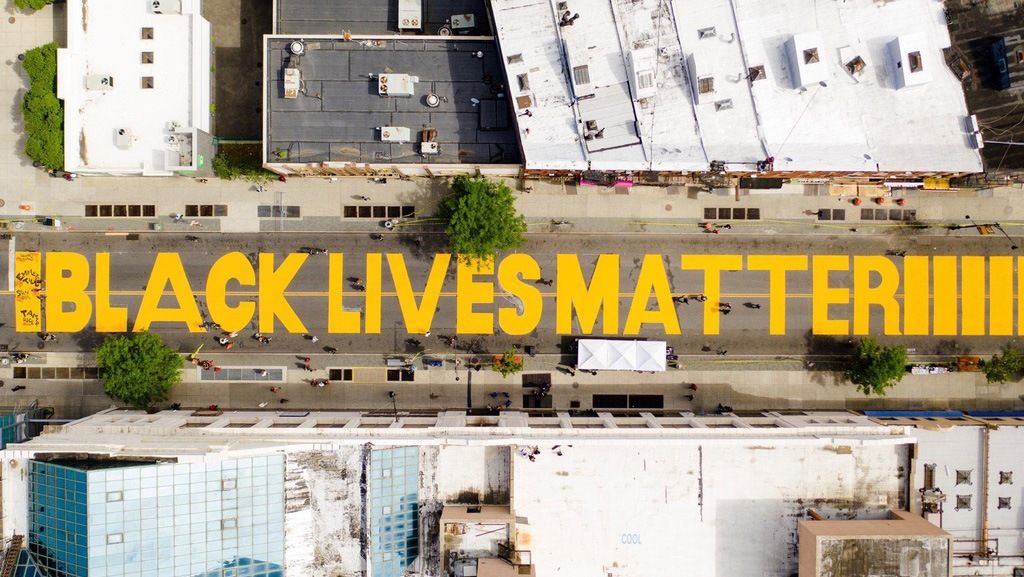

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner Photo: “BLACK LIVES MATTER“ painted in orange on Fulton Street in New York City in June of 2020. UPI Photo via Newscom/Kyodo News Images.)