Has Japan Sidestepped a Pandemic Unemployment Boom?

Economy- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

The Country Gets Away with a Slight Increase

With the spread of COVID-19 cases, the government declared a state of emergency for seven prefectures in April 2020. This created unprecedented difficulties for many workplaces, such as the sudden suspension of normal work. The Labor Force Survey (Statistics Bureau, Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications) indicates that the number of employed persons fell sharply by 1.07 million (seasonally adjusted) from March to April. This sizable monthly decline is exceeded only by the decrease of 1.13 million recorded in December–January 1963 on account of heavy snowfall and is about twice the decrease of 520,000 occurring in February–March 2009 in the aftermath of a global financial crisis.

Meanwhile, the number of unemployed in April 2020 was up by 60,000 persons over the previous month, and the unemployment rate rose 0.1 percentage point to 2.6%. Despite the sharp contraction of the number of employed persons, though, a sizable increase in unemployment was avoided. This was the consequence of the number of involuntarily unemployed for such reasons as dismissals or contract terminations being unchanged since March. While momentarily exceeding 3% during the year, the unemployment rate averaged just 2.8% in 2020. It appears that unemployment during the pandemic has not been as serious in Japan as in other advanced economies.

Growing Numbers Give Up on Work

What explains the sharp decline of the number of employed persons being accompanied by only a modest increase in the unemployed? The first reason is the substantial rise in the number of people not in the labor force. This group is defined as those 15 years or older who are not looking for work or who are unable to begin working immediately when seeking work. Unemployed persons, meanwhile, are those who are without jobs but who are looking for work and are able to begin working immediately upon searching for a position.

The number of people in the former group, those not in the labor force, rose by 940,000 in the month to April 2020, an increase surpassed only by the increase recorded in January 1963. That winter, heavy snowfall kept people at home, and the number of people not in the labor force soared. In the current moment, fear of catching COVID-19 or stay-at-home appeals by the government meant that many people losing jobs did not become unemployed persons looking for work. Rather, by giving up working, they became people not in the labor force.

The increase in April 2020 of people not in the labor force largely centered on the elderly with a high risk of developing severe COVID-19 symptoms and on women concerned about their families. During Japan’s population decline since the 2010s, labor shortages have been moderated through the growth of the number of working elderly. The pandemic, however, has brought this trend to a halt. It is usually the case that women take care of the home in Japan, such as looking after children and caring for elderly parents. This has led women to give up working from worries about catching COVID-19 and from a desire to prevent household transmission.

Beginning in May 2020, the elderly and women began to rejoin the labor force due to an increasing need for income to support livelihoods and to the appreciation that hand washing and mask wearing help to prevent COVID-19 infections. However, as cases spread rapidly in 2021, the number of people not in the labor force turned to rise, and a situation is continuing where people are giving up working from their fears of becoming infected.

Compared to the downward trend before the pandemic, I estimate that people not in the labor force have increased by more than 1 million at a maximum. Had these people remained in the group actively seeking work, the number of unemployed would have risen by 2 to 3 million and the unemployment rate would have climbed to around 4.5%. Should the risk of infection be reduced to some degree, inducing many of the people not in the labor force to begin looking for work, the unemployment rate could increase going forward.

Since the second half of the 2010s, legal and regulatory changes have promoted the employment of women and the elderly, and the number of employed persons has increased despite the contraction of Japan’s population. The number of people not in the labor force returning to its former downward trend, which had increased due to the Covid-19 pandemic, will profoundly influence the long-term trend of Japan’s economy burdened with the structural problem of a shrinking population.

An Upsurge in Employed Persons Not at Work

Another reason why the economy has been able to avoid a significant increase in unemployment in the midst of the pandemic is the upsurge in employed persons not at work. The number of such persons likely reached a postwar high in April 2020.

Employed persons not at work are persons who are still employed but who are not performing their jobs. Such persons increased to a record high of 5.97 million, thereby accounting for 9.0% of all employed persons and marking an unprecedented year-on-year increase of 4.20 million. If these people had lost their jobs and joined the 1 million persons who left the labor force to look for work, the unemployment rate would have surpassed 10%.

As of April 2020, many employed persons not at work were in the sectors of accommodations and eating and drinking services. In these sectors, employed persons not at work climbed to 1.05 million from just 100,000 a year previously. With COVID-19 cases spreading in healthcare settings, employed persons not at work in the medical, healthcare, and welfare sectors doubled to 500,000 in April 2020 from the 250,000 of the same month in 2019.

Employed persons not at work include those who are not working for personal reasons, such as people taking leave or caring for children or other family members. It was, however, employed persons not at work for company reasons who increased sharply in the spring of 2020. In the first quarter of 2020, out of the total of employed persons not at work, 13.5% were in that position due to company reasons; this figure more than doubled to 38.7% in the second quarter.

The increase of employed persons not at work for company reasons is thought to be explained by many corporate managers believing as of April 2020 that the contraction of business, or the worsening of earnings, would be temporary in nature. They therefore sought to ride out the situation by suspending business operations. They anticipated that the lifting of the state of emergency would be followed by the prompt recovery of earnings and the immediate need for workers. Bearing in mind forecasts for the long-term shortage of labor, companies hesitated to dismiss workers in view of the difficulty of recruiting them. Such reasoning resulted in the upsurge of employed persons not at work.

Government employment policies also contributed to the increase of employed persons not at work. In the early stages of the pandemic, the government tapped the ample resources of employment insurance and instituted a series of emergency measures, such as the expansion of subsidies to maintain employment and the easing of eligibility restrictions to obtain them. These temporary measures helped to reduce labor costs and contributed to companies’ decision to suspend business operations.

After surging in April 2020, the number of employed persons not at work fell by half in May, and many such persons were able to return to work. By autumn, this figure returned to its prepandemic level. With COVID-19 regaining force in February 2021, employed persons not at work rose somewhat, but not as far as in the previous year. Today, more than 18 months since the initial announcement of emergency measures, the government is running out of resources for its policies facilitating business suspensions. Although such suspensions momentarily forestalled a sizable increase in unemployment, employment-maintenance measures are encountering limits, and the risk of higher unemployment is growing.

Nonregular Employment and Telework

While Japan has avoided a sizable increase in unemployment in the pandemic, the disparity between regular and nonregular employment, which has widened since 2000, has grown further.

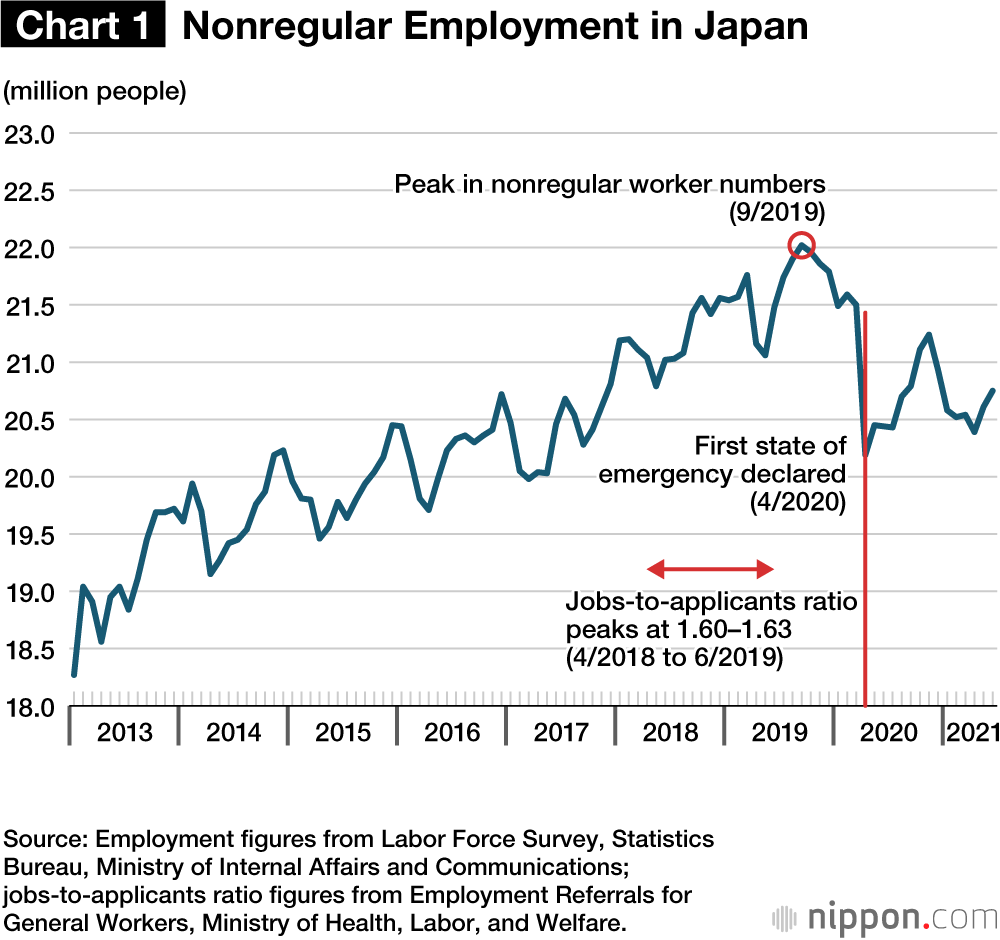

Chart 1 illustrates the trend for the number of nonregular employees. Such employees decreased by more than 1 million in April 2020 against the previous month as COVID-19 cases spread. Employees were dismissed in the eating and drinking, manufacturing, and other industries; many of them, as noted above, were the elderly or women in nonregular positions who voluntarily decided to leave their jobs. For example, the closing of all primary and secondary schools resulted in mothers in part-time positions leaving their jobs out of concern for their children at home.

From the spring of 2018 to the summer of 2019 preceding the pandemic, labor was in extreme short supply in Japan, and a huge increase in job offers led to the growth of nonregular employment. As companies responded to the acceleration of demand prior to the increase of the consumption tax in October 2019, the number of nonregular employees reached an all-time high of 22 million in September.

Having grown steadily for some time, the number of nonregular employees began to trend downward in October 2019. In January 2020 before the pandemic became widespread, nonregular employees had dropped by about 500,000 from their high of three months ago. Even without the spread of Covid-19 cases, nonregular employees had entered a correction phase around 2019 year-end. Such employees began to recover in July 2020 but then turned to decline when Covid-19 cases started climbing in November. The number of nonregular employees is currently far below its September 2019 high.

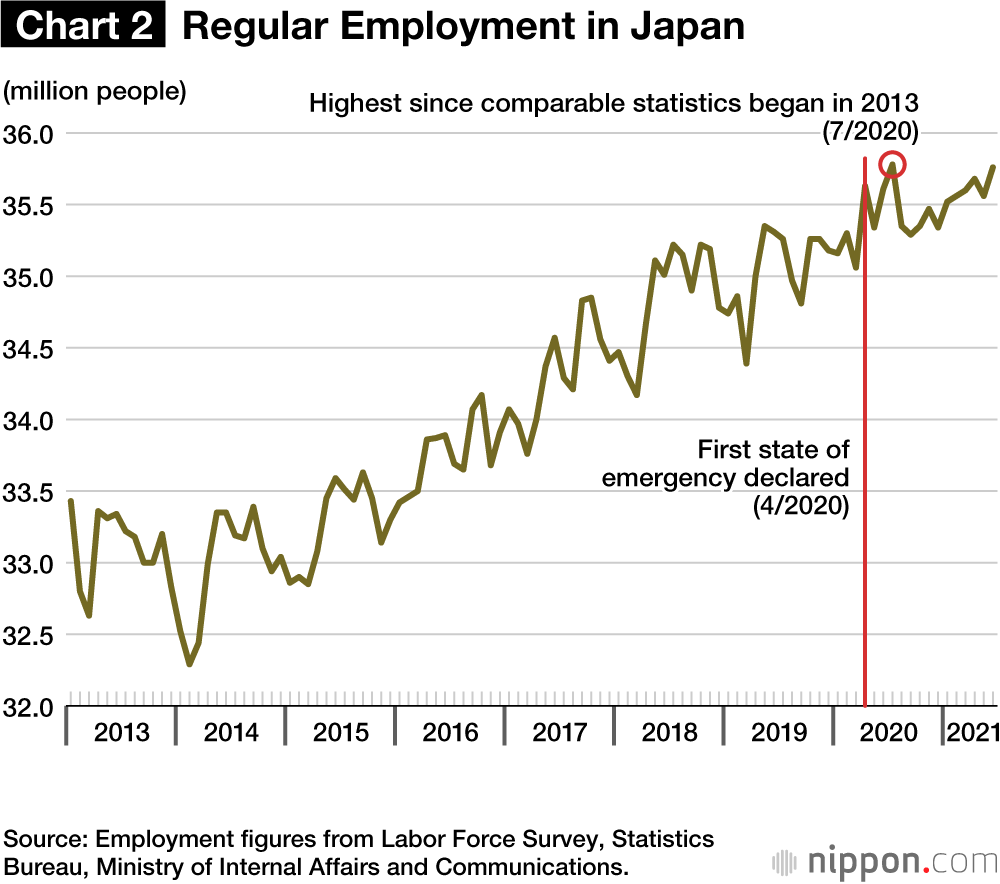

Surprisingly, when a state of emergency was declared in April 2020, the number of regular employees was at its highest level since 2013 (Chart 2). Regular employees then climbed further with the lifting of the state of emergency in July. While the number of regular employees then stalled momentarily starting in August, its upward trend from before the pandemic has continued. As a result, the number of regular employees has returned to the 35 million level for the first time since 2002, a year that experienced a serious economic downturn.

Regular employment is often said to be generously protected during economic downturns in Japan, and this was also the case with the pandemic. The exception is the period between the second half of the 1990s and the first half of the 2000s, when companies made major adjustments to employee levels. That such adjustments did not occur with the pandemic is another reason why an increase in unemployment was avoided. The disparity between regular and nonregular employment, however, has widened.

With regard to the increase of the number of people giving up working or to the decrease of nonregular employees, some of these people may have been able to keep working through teleworking. Government and private-sector surveys disclose that teleworking had a penetration rate of about 30% at its peak. In the spring of 2020, many people began working from home for the time being, but then subsequently returned to the office.

Teleworking has spread among the employees of large companies and among regular employees in specialist positions. It has not seen similar uptake among small and medium-sized enterprises or among the many women and elderly working as nonregular employees in generalist positions, though. Spurred on by the pandemic, the expansion of opportunities to work from home will be indispensable in broadening further the ways of working in Japan.

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photograph: People in front of Tokyo Station heading for work on April 26, 2021, the first Monday morning after the third declaration of a state of emergency. © Jiji.)