JFL Today: Considering Japanese-Language Education for Foreign Residents

Vlas Kobara: Japanese Language Education Breaks Down Barriers for Foreign Children in Japan

Society Education Language- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

A Memorable Encounter

I was born in Khabarovsk, Russia, in 1992, after the collapse of the Soviet Union, but moved with my mother to Japan when I was five years old. We lived in Himeji, Hyōgo Prefecture, at first. A family story goes that when I entered nursery school, I insisted on wearing sunglasses and jewelry. Looking back, I suppose I was struggling in my own way to fit into Japanese society.

When I was little, there was one person, a man I met in a park in Himeji, who made a strong impression on me. He called me over and gave me candy and we talked. When I spoke about myself, I copied what my friends called me and said “Vlas-kun is...” but he corrected me, saying, “You don’t use ‘kun’ when you talk about yourself.” He also taught me the Japanese words for “bench” as well as “baseball,” pointing to a nearby game to explain a little how to play.

You might say he was a nosy old man, but when I think back now, he was only trying to bring me into the community of that park using simple Japanese. I was very lucky to meet someone like that and for the subsequent friends I have made, who helped me become part of Japanese society.

Foreign children can feel isolated, and I believe that Japanese educational spaces should create room for them to join and talk with people outside their families so they can get to know others in their community.

Sharing Dreams

I head the organization Supporting Foreign Children to Attend School, which provides 100 hours of free online Japanese language education to children who cannot yet speak Japanese well. The aim is to give them the minimum level of language ability to participate in school lessons. Our basic financing is through crowdfunding, with lessons being run with the help of students from Reitaku University.

An online session to support foreign-born children in Japan to enroll in Japanese school. (© SFCS)

The children often struggle to simply introduce themselves, and sometimes break into tears during the lessons. But they learn words quickly. After around 30 hours, they can talk about their favorite anime and tell us about their marks in school. After 100 hours of lessons, some children are even able to describe what they want to be when they grow up.

Of course, 100 hours is not sufficient to master Japanese. But it is enough to make Japanese friends and to give people the confidence to say, “It’s all right for me to be here.”

Children typically do not have a say in their parents’ decision to move to Japan. In the country, they suddenly find themselves face to face with a language barrier that makes it nearly impossible to communicate with their peers and others around them. Imagine being in a class where you are the only student who does not understand the words being spoken. It goes without saying that it is a stressful experience. That is why we need to create environments where children are not isolated and are able to express their thoughts.

The SFCS was established in 2021, and I became director in 2022. I am charged with raising awareness of the need for Japanese language education for foreign-born children and supporting and interacting with our students, including speaking at the program’s graduation. Acquiring Japanese language skills is a comprehensive process that cannot be easily divided into areas like study or play, which is why instructors need to be clever in their approaches.

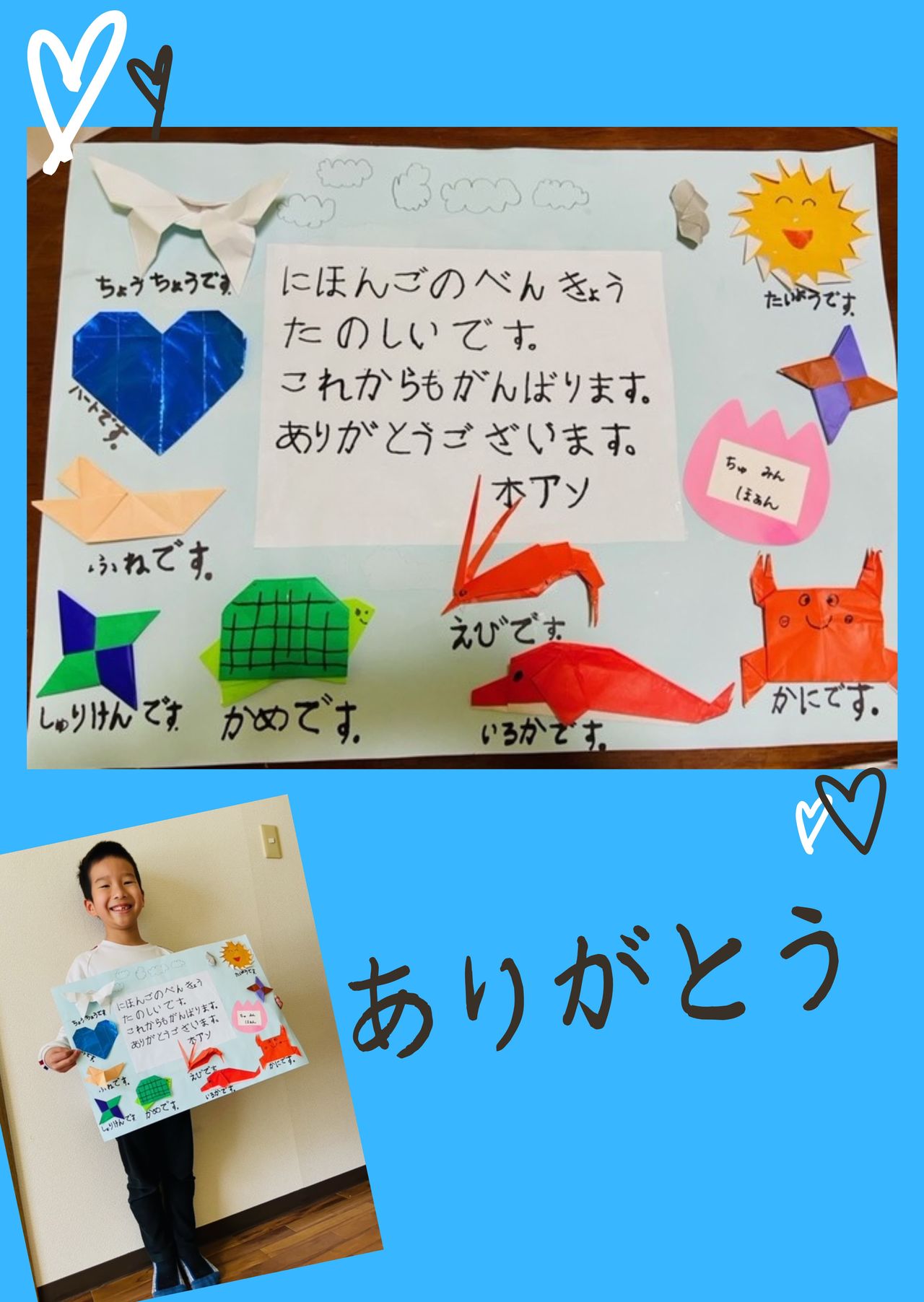

A letter of thanks decorated with origami from a child who went through the SFCS Japanese lessons. (© SFCS)

Lack of Understanding Builds Up

As Japan’s foreign population increases, there is talk of closed communities of, say, only Vietnamese or Chinese resident, who isolated from their Japanese neighbors struggle to come to terms with Japanese society and share their grievances to blow off steam. If there is not a way for such groups to communicate with Japanese people directly to learn how they see the world, then such foreign communities run the risk of growing ever more polarized and the views of members becoming more extreme. If Japanese people can learn more about the reasons behind foreign residents’ behavior, though, we can find better balance. The bridge spanning those two sides is the Japanese language.

The Japanese government has said that there are over 8,600 school-age foreign children in Japan who are possibly not attending elementary or middle school. Children who do not attend school or learn Japanese will not make Japanese friends or become attached to Japan as a country, leading to fractures in society. I have read numerous articles about immigration issues in Western countries that describe how many second-generation children who did not go to school ended up grouping together and forming gangs. Such stories negatively impact the immigration issue, fueling anti-foreigner sentiment and bolstering support to remove immigrants.

The value of learning Japanese for foreign residents in Japan is that it breaks down barriers. Being able to understand and answer someone or making friends with Japanese people are experiences that help open children’s minds, and I believe can lead to a society that is better for everyone, foreign and Japanese alike.

Vlas Kobara recording a podcast. “If you look at reality with clear eyes, you soon see what’s needed right now.” (© Almost Japanese)

“We Have to Live Together.”

Anti-immigrant sentiment is growing in Japan and around the world. But what if in this country we could go back to earlier times, before such negative views had gained a foothold and ask people whether they wanted to reject immigrants. I think the majority of people would not be anti-immigration and be open to taking in foreigners.

This is because immigration is an economic necessity. Japan’s population is falling and foreigners support Japanese society by working, paying taxes, and paying into the national pension. For better or worse, we are in a time when we have to live together.

As the foreign population grows, we frequently hear phrases like “cultural diversity” and “coexistence.” These are important ideas, but Japan does not have to embrace every aspect of foreign culture brought by immigration. It is not necessary nor possible to understand everything about each other. Rather, people should find those aspects that they can embrace, and distance themselves from those that are hard to accept. What is important is to strike a balance.

I want foreigners coming to Japan to know that the country is not suited to everyone. There tends to be a rosy image of Japan being warm, open, and peaceful. I agree that it is a wonderful country with lots of great people, but there are certain types of individuals and points of view that are hard for foreigners to come to grips with. Similarly, there are Japanese people who have no interest in understanding foreigners’ points of view. This is a reality that must be accepted, making it all the more important that foreign residents strive to communicate with Japanese people in their own language.

Private Sector Taking Action

I am uncertain what official measures Japan is taking to support immigrants, but there are many individuals in the private sector who are taking action. When we put out the word looking for cooperation in Japanese language education, we had lots of people volunteer to help or support our crowdfunding efforts.

The current situation is less about waiting for the government to take the lead and more centered on private citizens and organizations taking action because they see a need. One problem, however, is a lack of coordination among different projects. To bolster collaboration there needs to be more information sharing and integration among the different support organizations.

I want to help foreign children learn not to be afraid of interacting with Japanese people and the broader society by giving them the skills and experience to communicate effectively. I want more foreigners to be able to express themselves, and to create an environment where they can feel comfortable with the way of studying in Japan, attending Japanese schools, and being a part of a society where friends from different backgrounds can accept each other. This starts with the simple joy of having someone understand what you are saying.

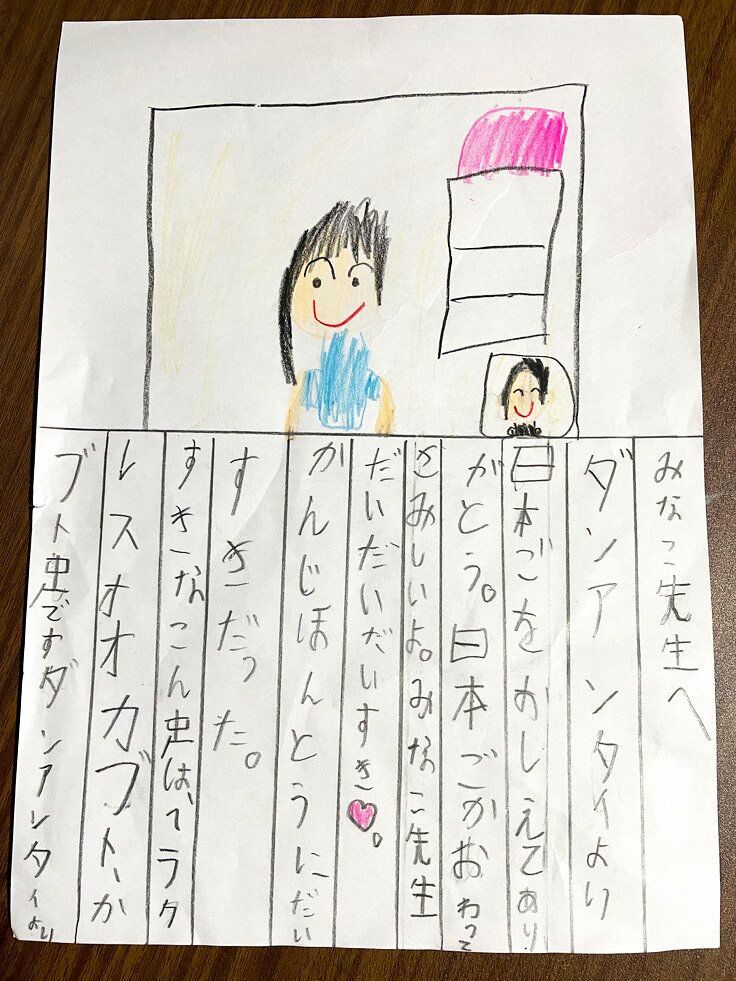

A diary page written by a foreign-born child who learned Japanese through SFCS online program. (© SFCS)

I believe that a society where any child can feel like they belong benefits everyone, Japanese and foreign resident alike.

It is important to discuss what is working and deal with ongoing issues. It is not enough merely to point out that there are children who are struggling to fit in at schools. It is vital to show that there are children who are succeeding and have found their place in Japan. I believe that sharing positive examples builds the desire to change society.

(Originally published in Japanese, based on an interview by Matsumoto Sōichi of Nippon.com. Banner photo © Ochi Takao.)