JFL Today: Considering Japanese-Language Education for Foreign Residents

Volunteer Language Support for Foreign Children in Kawaguchi, Saitama

Society Education- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Four Decades of Helping People in Kawaguchi

The entrance to Cupola, a public facility in front of JR Kawaguchi Station, features colorful posters announcing a variety of Japanese classes for nonnative speakers. These classes are offered by the Kawaguchi Voluntary Evening School, established 40 years ago. When I visit the classrooms at Cupola, I see that the desks are occupied by a number of foreign language learners, assisted by volunteer staff.

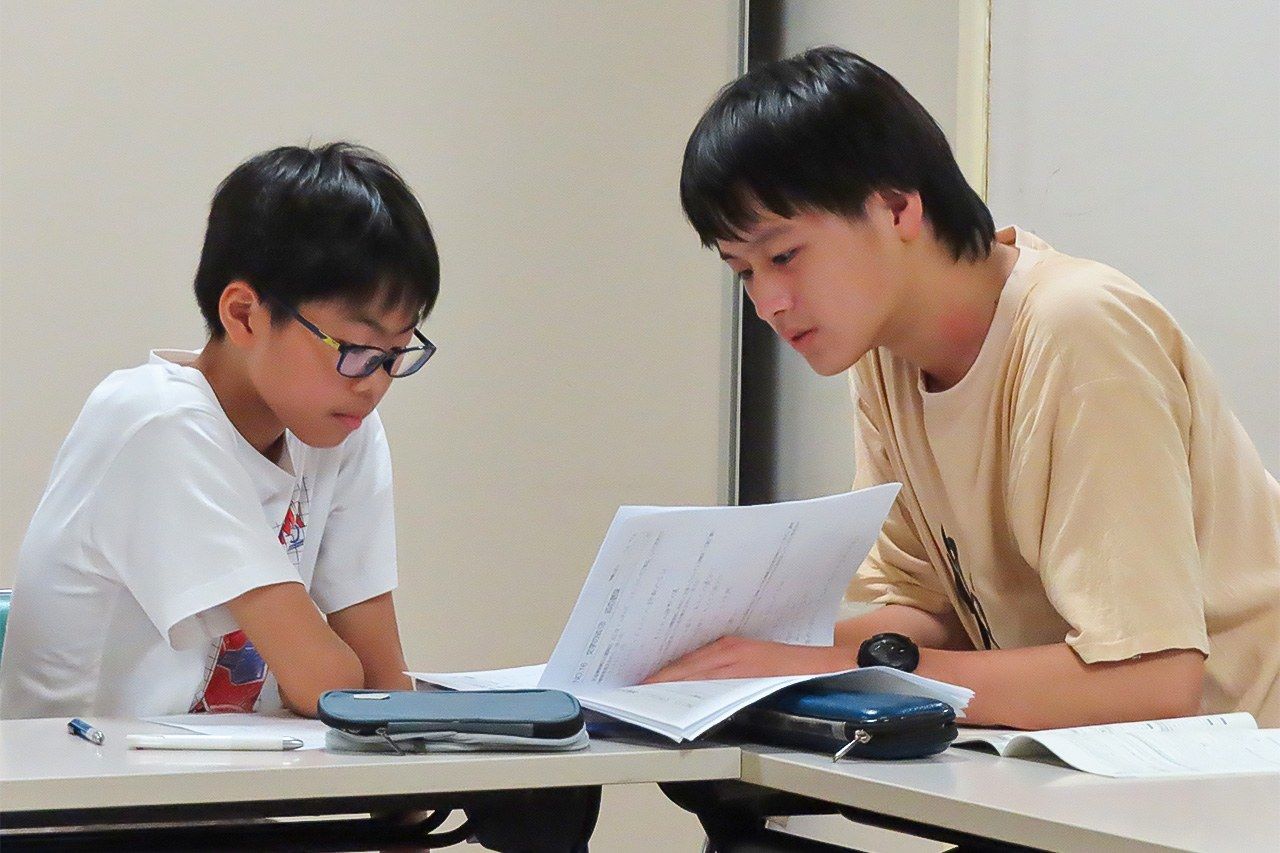

A male Chinese high school student learned Japanese there and succeeded in entering one of Saitama Prefecture’s top high schools. He is now coaching a younger Chinese student, all the while continuing to study Japanese himself. He credits the class’s environment for helping him to learn naturally and feel comfortable asking questions.

Non-Japanese students studying at the school can sometimes be seen coaching younger students. (© Tanaka Keitarō)

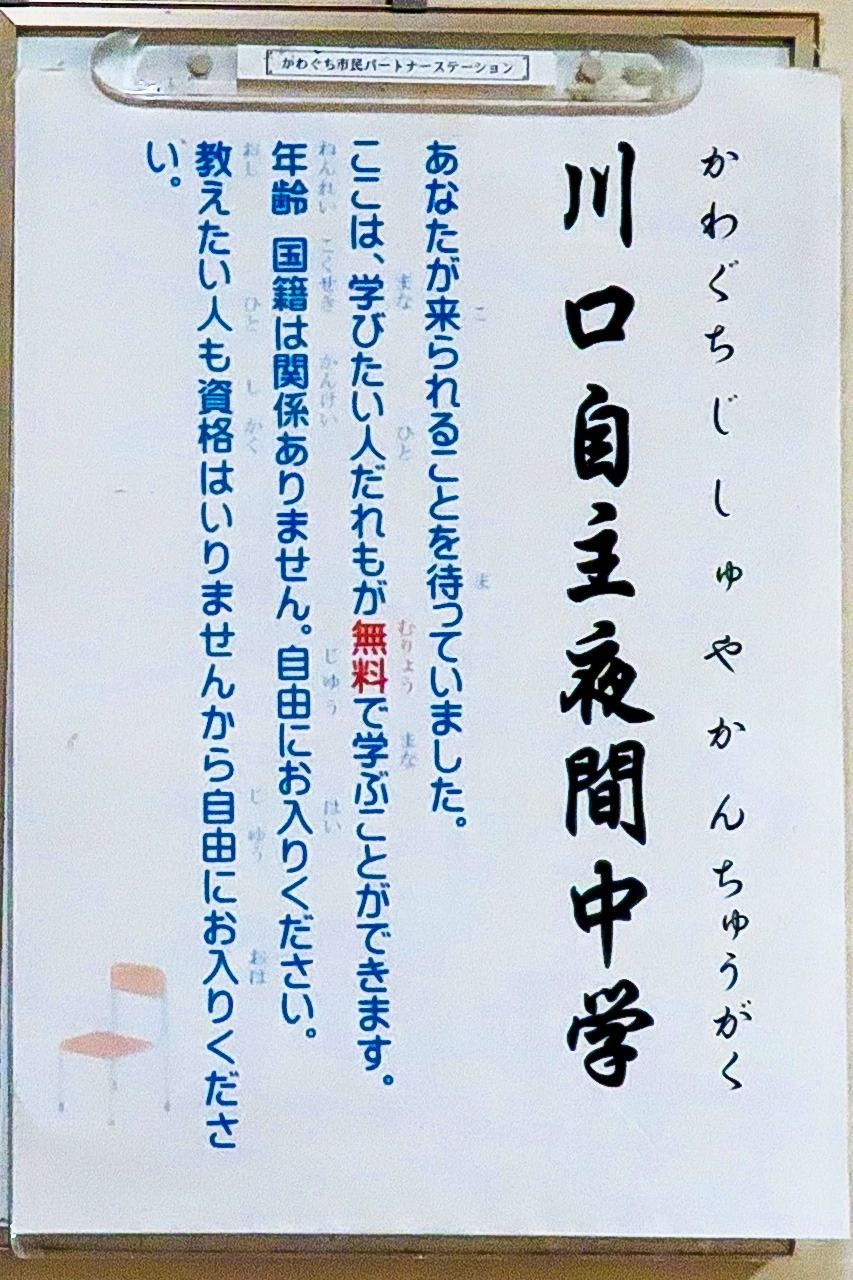

A sign at the facility welcomes new participants to the Kawaguchi Voluntary Evening School’s programs. (© Tanaka Keitarō)

A poster at the classroom’s entrance says: “We’ve been waiting for you to come. Instruction here is free of charge. Anyone, regardless of age or nationality, can attend. Please feel free to come in. Anyone willing to teach is also welcome; no qualifications needed.”

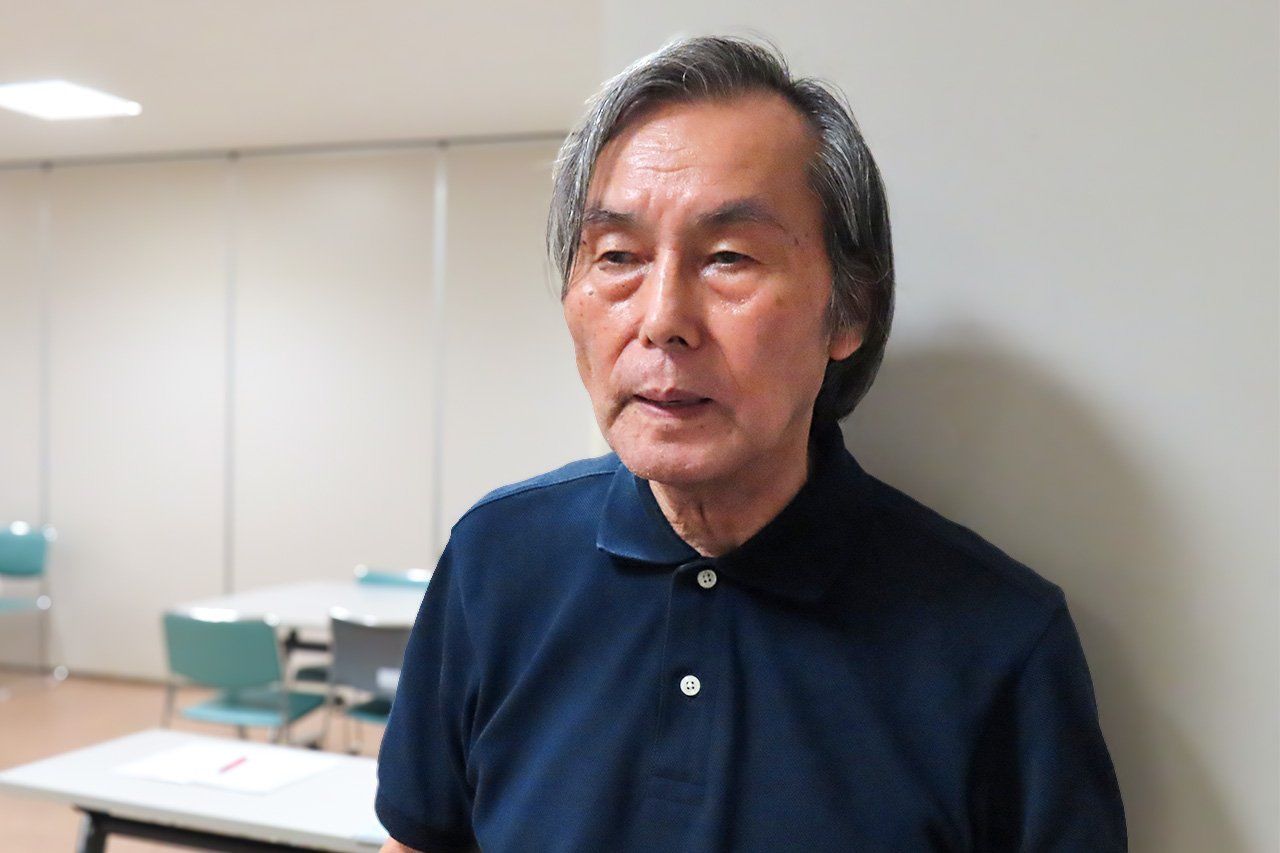

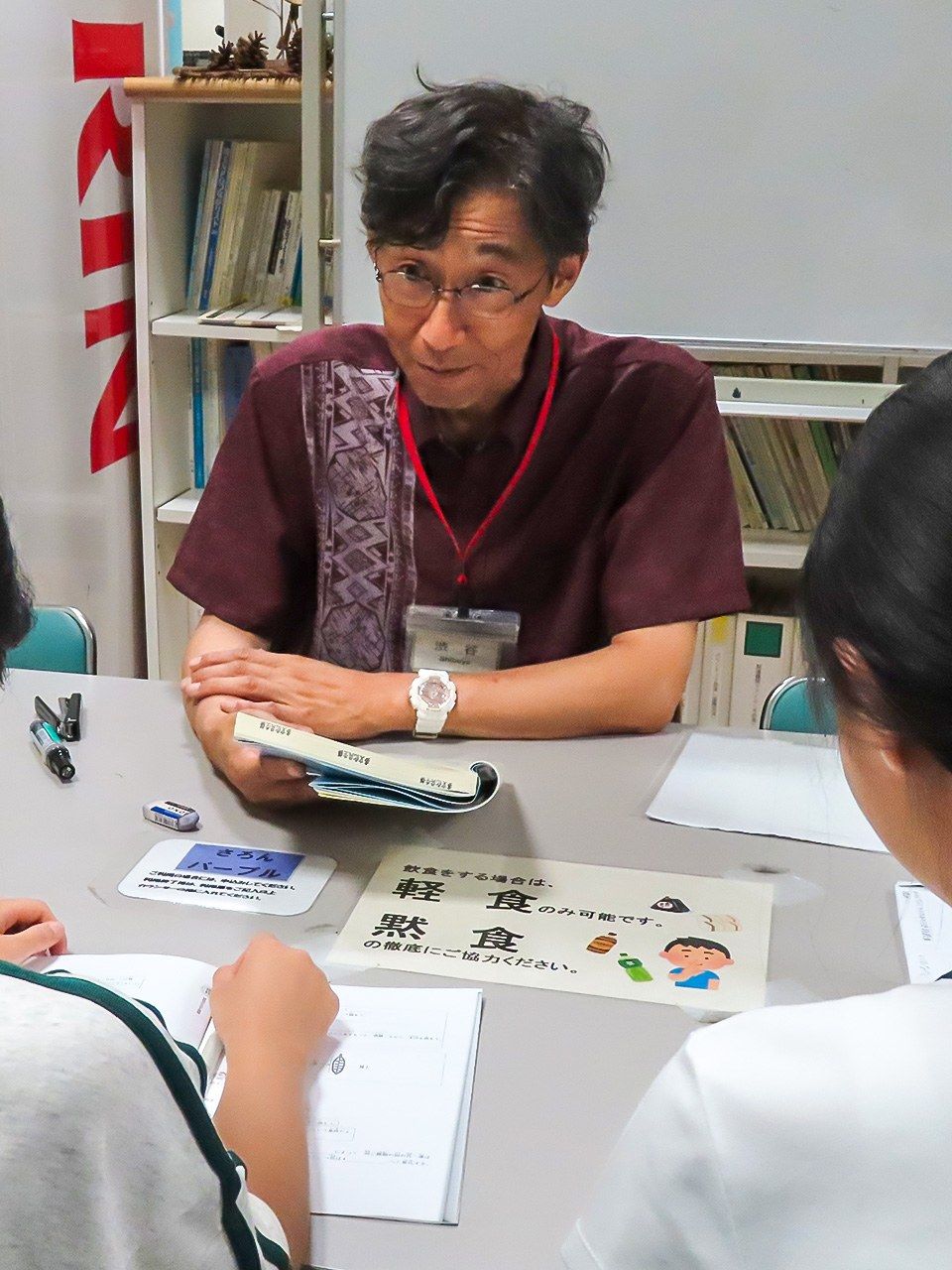

Nogawa Yoshiaki, a former public servant, heads the program. He recalls: “At first, we had six students, and they were all Japanese. At one point, we welcomed many students who were not attending regular school, but now, many of our students are non-Japanese. I often hear it said that night schools expose the cracks in our society.” Due to a lack of staff, the program currently accepts only students aged 13 and up, and there is a waiting list for those wishing to attend.

The operators of the Kawaguchi Voluntary Evening School also urged local government authorities to establish after-hours learning programs for Saitama residents. The school’s extensive track record helped persuade the authorities to set up the Yōshun Branch of Shiba-Nishi Junior High, a public night school that opened in April 2019. It is near Shibazono Danchi, a public housing complex where the majority of residents are Chinese. Although instruction is primarily geared to native Japanese speakers past the compulsory school attendance age, the school also accepts non-Japanese learners.

Kawaguchi Voluntary Evening School head Nogawa Yoshiaki. (© Tanaka Keitarō)

“We Want to Help Them Thrive”

There are also a variety of programs focusing on children ages 6 to 15; the oldest program is the Kawaguchi Japanese Class for Children. Many of the students attending are Chinese or Vietnamese, and more and more younger children, ages 6 to 8, are joining. The vice head of the program, Shibuya Jirō, says: “Even though foreign children receive Japanese instruction in school, many of them may not have the vocabulary necessary for absorbing subjects such as mathematics or social sciences.”

The Kawaguchi Japanese Class for Children, where many students are from Vietnam or China. (© Tanaka Keitarō)

The program’s staff are unanimous in wanting to help the children thrive and to give a hand up to those who want to learn. The driving force behind their efforts is a sincere desire for foreign children who will be living their lives in Japan to create bright futures for themselves.

School Lessons Not Enough

According to a Kawaguchi Board of Education survey conducted up through May 2025, around 3,000 non-Japanese children attend the city’s public elementary and junior high schools. Of these, 1,600, 60% of whom are Chinese and 20% from Turkey, require Japanese-language coaching.

The city has over 90 instructors on hand to provide supplementary Japanese instruction. The program is thus relatively well staffed, but the basic Japanese the children learn in school is not enough to allow them to follow lessons effectively. Satō Akinori of the municipal Board of Education says: “Although the children can converse in Japanese, they will not be able to understand lessons well if, for example, they are not familiar with terms like ‘vertical’ or ‘horizontal’ used in mathematics.” That is why, for children who want to learn more, Japanese teaching offered by civic groups is an essential complement to school instruction.

Diversity in Response to Local Issues

Professor Tsuboya Mioko of Yokohama City University, an expert on support for non-Japanese children, says that Japanese language support volunteer programs for adults began throughout the country in the 1970s, when Japan admitted refugees from Vietnam and surrounding countries during the conflict in Indochina. Later waves of foreign adults admitted to the country included young Japanese left behind in the turmoil after World War II who had grown up in China, and South Americans of Japanese descent. Support programs further expanded after the 1995 Hanshin-Awaji earthquake, and new programs targeting children also sprang up.

Today, the aging of volunteers who have supported these programs over the years, a lack of successors for them, and the unstable financial conditions are some of the issues the programs face. The situation is no different for the Kawaguchi volunteers.

The Act on the Promotion of Japanese-Language Education, enacted in 2019, incorporates policies for expanding opportunities for non-Japanese to learn the language. This national legislation sets out the roles of community groups in teaching Japanese, along with the education system, and indicates that the government will continue to rely on community support for Japanese instruction.

A Shifting Political Environment

In Kawaguchi, citizens have played a leading role in promoting coexistence with their non-Japanese neighbors, as exemplified by Shibazono Danchi, where the majority of residents are Chinese. More nationalities are flooding into the city, though, and conflicts over issues like trash disposal and noise due to differing customs are becoming more common. In the July House of Councillors election, some candidates spoke in terms that could be construed as exclusionary to foreigners. Ōtsu Tsutomu—a newcomer candidate from the Sanseitō party, which takes a “Japanese first” line—won a seat representing Saitama Prefecture while taking nearly 42,000 votes in Kawaguchi, 16% of the total cast and the highest count in the city.

The Evening School’s Nogawa Yoshiaki expresses concern at this result, saying, “In the context of electioneering, hate speech toward foreigners has become normalized.”

Shibuya Jirō of the Kawaguchi Japanese Class for Children adds: “Due to the dwindling Japanese labor force, the country needs workers from abroad. The issues Japan faces are not so simple that they can be addressed with stricter measures regulating foreigners. In fact, the focus should be on ensuring that foreign workers’ children are educated in a manner that will help them prosper in our society.”

But even given concerns about hate speech, Japanese classes for non-Japanese steadily continue in Kawaguchi. The reality, after all, is that there are children who need support, and Japanese people ready to offer it. Further ways of attracting more participants, both Japanese and non-Japanese, are being explored.

Shibuya Jirō has been involved in teaching Japanese to children for over 10 years. (© Tanaka Keitarō)

Helping Kurdish Children Acquire Japanese

Among the foreign residents of Kawaguchi, news reports highlight the presence of a sizeable number of Kurds who fled the threat of ethnic violence in Turkey. They have been refused refugee status by the Japanese government, though, and many of them are on provisional release from immigration detention facilities on humanitarian grounds. There are an estimated 400 Kurd children living in the city. A Japanese class run by Komuro Keiko offers instruction to 50 of these children aged 6 to 18, where they pay ¥200 per lesson, and Komuro personally makes up the difference between income from the classes and expenses.

Komuro Keiko heads the Japanese language class for Kurds. (© Matsumoto Sōichi)

Lately, she has felt that citizens’ attitudes toward the rapid increase of foreign residents in their city are changing. She believes that about 10% of Kawaguchi’s Japanese residents feel they should get along with their foreign neighbors and 20% do not see foreigners in a positive light, while the bulk of the Japanese think that the issue doesn’t concern them.

Komuro herself has seen Kurd children become increasingly unruly. “Some of the children face double language limitations, being proficient in neither their first language nor Japanese. The older children, in junior and senior high school, lack sufficient vocabulary and find it difficult to express themselves well, so they become discouraged.”

Foreigners under provisional release have only limited opportunities to work and restricted access to social security benefits, leaving some in dire straits. Komuro offers support to children through her Japanese class. She says “I want to do something before the children start engaging in problematic behavior. These children did not arrive in Japan of their own free will, but I want them to live happy lives.”

Volunteers Need Support Too

Professor Tsuboya of Yokohama City University says: “Local Japanese classes started at the initiative of volunteers have gradually spread, and have notably helped foreign children to advance to higher levels of education. Meanwhile, the number of foreign children in Japan has grown at a rapid clip, and there are not enough volunteers now. To ensure that such Japanese classes can be sustained, the authorities should support volunteers by offering help in the form of funds and venues, and assist volunteer groups in forming nonprofits to buttress their credibility. Steps should also be taken to involve individuals with ties to other countries, students, and other actors to nurture the next generation taking on the task of grassroots Japanese language education.”

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: Posters promoting Japanese language classes on a bulletin board in a facility in Kawaguchi, Saitama Prefecture. © Matsumoto Sōichi.)