Getting Everyone Ready: Toward Foreign Participation in Disaster-Preparation Activities

Society Disaster- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

As more and more foreign nationals choose to stay for extended periods or reside permanently in Japan, and as the surge of foreign tourists visiting the country grows, an increasing number of these people are falling victim to the earthquakes, typhoons, floods, and other natural disasters that so frequently strike Japan. This drives the need for disaster-preparation measures that encourage the active participation of foreign residents and tourists. This article takes a look at disaster-mitigation measures that include foreign people at the community level and the problems that still need to be addressed.

The Need for Inclusiveness

There are two important reasons to include foreigners in community efforts to minimize the impact of natural disasters.

One is to assure foreigners—including tourists as well as long-term foreign residents—that Japan is a safe and secure country. Providing useful disaster information is a critical part of Japan’s welcome to the numerous foreign visitors who are expected to arrive for the various international events that will be taking place in Japan over the next few years. As the host country, Japan has a responsibility to provide a safe and secure environment for everyone, including tourists and those who come to work here, and ensuring that there are community-centered disaster prevention programs that include foreigners is part of this.

Second, when disaster strikes, everyone in the community—whether residents or people just passing through, whether Japanese or foreigner—must pitch in and cooperate to keep damage to a minimum. Working together and helping each other is how communities can best overcome any devastation that may ensue from a natural disaster. And for people to cooperate, they need to share information. Foreign nationals who may happen to be in the community at the time, whether long-term residents or tourists, are just as much victims of a disaster as anyone else in the community. They need to be treated as equal partners rather than guests when it comes to dealing with a disaster.

What factors need to be considered when involving foreigners in local disaster prevention efforts?

Suppose a Japanese tourist in a gift shop in the Middle East was suddenly warned, “A sandstorm is coming. Watch out!” The Japanese people are not familiar with sandstorms and have no idea how dangerous they might be. Will the storm pass in one hour or one week? What happens in a sandstorm? The Japanese tourist is not going to know how to “watch out,” even assuming he or she understands the language in which the warning was delivered.

The first step to involving foreigners in disaster prevention measures is to provide multilingual translations of helpful disaster-mitigation information. Language is obviously the very first barrier that must be overcome. It is not enough, though, t simply translate information crafted originally for domestic audiences. Not everyone will be familiar with typhoons or earthquakes. The nature of the disaster also needs to be explained, just as the Japanese tourist mentioned above needs to have explained what happens in a sandstorm.

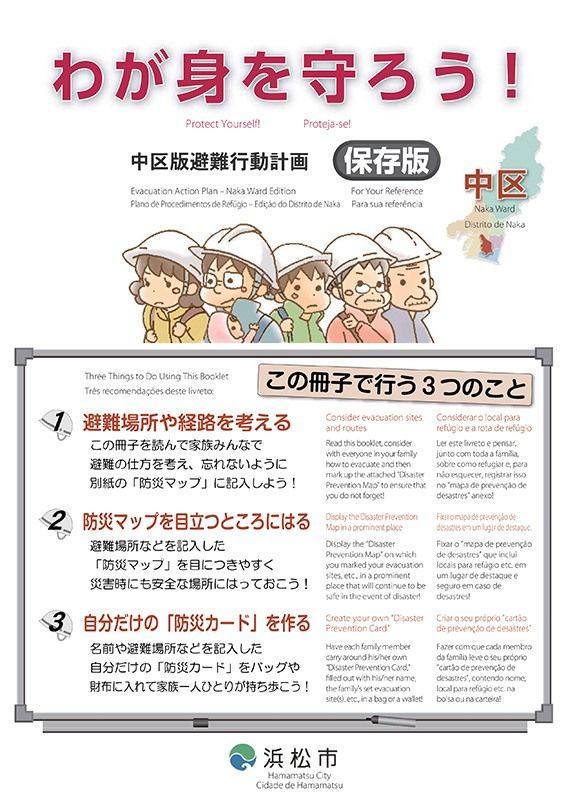

The cover of a disaster manual published by the city of Hamamatsu, Shizuoka, in Japanese, English, and Portuguese.

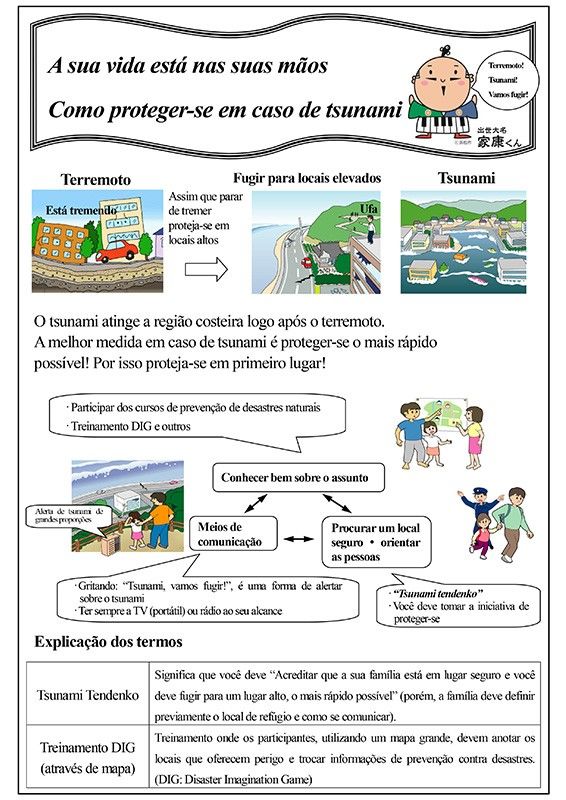

The Portuguese edition of the Hamamatsu manual is illustrated with simple pictures showing what can happen when a tsunami strikes.

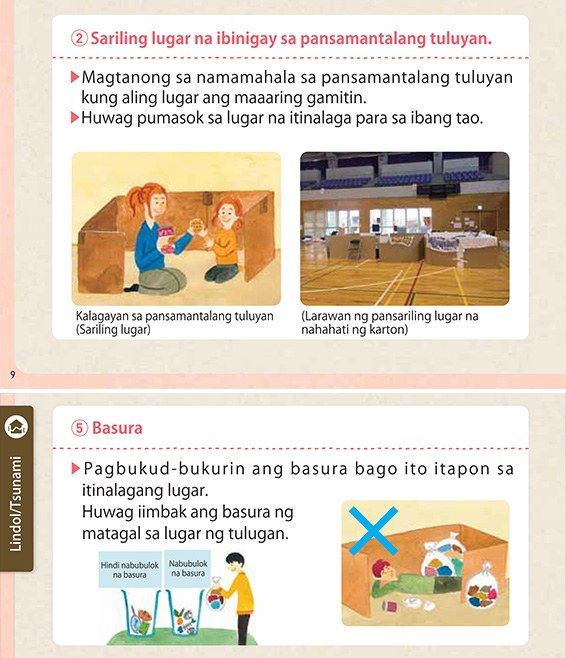

This Shizuoka Prefecture disaster manual published in Tagalog explains what life is like in an evacuation center with simple illustrations.

An increasing number of local governments are providing multilingual hazard maps to people in their communities, but here, too, special precautions are needed. In numerous countries, roads have names, and the houses and buildings along them are numbered consecutively so that it is easy to find them on a map.

In Japan, however, with the exception of a handful of places like Kyoto and Sapporo, houses and buildings are identified by block, district, and city subdivision numbers. Few roads have names, there are numerous alleyways with houses tucked in one behind another, and numbering is not consecutive. The hazard maps are intended to show evacuation routes, but they can be hard for foreigners to decipher.

Another problem to recognize is that providing information in diverse languages is of no help if that information does not reach its intended audience. Many foreign residents remain unfortunately unaware that their communities have multilingual hazards maps available.

It is not enough to translate disaster-related information. Effective means of disseminating the information is also essential. Some of the multilingual information currently being provided to resident foreigners could also be useful to the growing number of overseas tourists visiting Japan; the availability of this information needs to be advertised more broadly.

Another factor that must be addressed are the dietary restrictions imposed by different cultures and religions. This will be especially important when people are compelled to live at evacuation centers for an extended duration following a major disaster.

Local Communities Must Take the Lead

The conventional practice has been to designate foreigners as “disaster-challenged” persons requiring special assistance. Certainly, differences of language, culture, and experience do exist, but it seems premature to dismiss foreign residents as needing special help when with just a little effort they could be made active participants in the disaster-mitigation efforts of a community.

In a survey I conducted of foreign residents in the Tōkai region, a large number of respondents said that in the event of a major disaster, everyone in the community should act to help each other regardless of nationality. Some of the things foreign residents said they could help with included preparing and distributing food at evacuation centers, assisting with the care of children and the elderly, putting out fires, and pumping out flood waters.

Far from being “disaster challenged,” foreigners have the potential to be major participants in disaster-mitigation efforts. Japan’s declining and aging population means that in many communities, elderly Japanese residents are more likely to be the ones who are challenged when disaster strikes. The full participation of foreign residents will therefore be more important than ever. And to achieve this, Japanese residents need to be equally aware of the kinds of disaster information available to foreigners and how to access that information themselves.

This is just one very simplistic overview of how foreigners can be included in local disaster prevention activities throughout Japan. In our daily lives, we inevitably categorize people by their ethnic origins, language, and religion—categorizations that are sometimes necessary and effective. When disaster strikes, however, the first priority is how to save oneself and how to save others. Cultural and social categorizations become meaningless.

In any kind of disaster, the protagonists are the people who are there at that moment in time. The very first efforts at disaster mitigation are local and regional, and these efforts must be facilitated by measures that overcome the barriers of language and cultural differences. Who knows: As we work to develop ways of coping with disasters so that foreigners can play an active role, we may discover new ways to peaceful and proactive coexistence.

(Originally published in Japanese on December 20, 2018. Banner photo: Travelers stranded at Kansai International Airport on September 5, 2018, by Typhoon Jebi. © Jiji.)