Hitler Reappears on a Tokyo Stage

Society- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

The Tokyo University of Foreign Studies holds an annual campus festival, Gaigosai, at which the main attractions include plays staged by students in the languages that they are majoring in. For the festival held in autumn 2018, TUFS’s German majors put on Er ist wieder da (He’s Back), a play based on the 2012 novel of the same title by Timur Vernes—a work that made its way to the silver screen in 2015 in addition to being translated into English as Look Who’s Back and into Japanese as Kaette kita Hitorā (The Returned Hitler). It was standing room only in the 500-seat auditorium where the play was staged on November 25; some interested viewers had to be turned away at the doors.

As the original story goes, when Adolf Hitler suddenly reappears in Berlin in 2012, everybody assumes that he is an impersonator, and he ends up becoming popular as a satirical comedian. The villain inside him remains concealed to the end. The version performed by the TUFS students turns the black humor of the original into something more serious: Hitler, after establishing his presence by appearing on television and using online media, moves on to the world of politics. And at the end of the play, the narrator observes, “At first we thought we were laughing at him, but now we realize that we’re laughing with him.” The message is that today’s world has become a place where a revived Hitler could find acceptance and support.

After Germany was defeated in World War I (1914–18), the victorious powers imposed crushing reparations on it. From the end of the 1920s into the 1930s the country was hit by the global Great Depression. This pair of blows caused inflation to rage out of control, reducing the mark to a trillionth of its former value. It also resulted in massive unemployment, leaving crowds of jobless people out on the streets. This was the environment in which Hitler achieved his rise to power.

Does today’s world have anything in common with Germany in the post–World War I period? In response to this question Satō Hajime, the third-year TUFS undergraduate who played the lead role in the play, replied, “I believe that there was tremendous dissatisfaction and anxiety among the German people in those days. And though the issues have changed, I can see considerable similarity in the great dissatisfaction that people today feel regarding problems like the influx of refugees into Europe.”

The original work was set in the Germany of 2012, the year the novel was published, but for the 2018 Gaigosai drama the students at TUFS moved the story forward to the current year. Over the six intervening years, the wheel of world history had taken a major turn: The United States had elected President Donald Trump with his America First agenda. Britain had decided to pull out of the European Union. And xenophobic and far-right forces had been on the rise in countries throughout Europe. These are just some major examples of the shift toward insularity that has been progressing on a global scale. The factors underlying this development have included the widening of income and wealth inequalities, massive inflows of immigrants and refugees, and the rise of unemployment, all of which have had a destabilizing effect on national societies.

When it comes to feeling dissatisfaction and anxiety, people in Japan are no exception to the global trend. As Satō sees it, the growing inequalities within society are a key characteristic of today’s Japan. “While some people enjoy extremely privileged lives, others find it hard even to provide themselves with the basics. Overall, the share of the population that is dissatisfied has been expanding.”

The Appeal of Populism

The play opens with the words of old woman who remembers Hitler and his Nazi dictatorship. “He was an awful one. Seventy-three years have passed since the world war ended. Are we any wiser now?” The setting is Germany in 2018. Hitler suddenly shows up, wearing his military uniform and a swastika armband. People assume he is a look-alike impersonating the long-dead dictator. The word of this impersonator makes its way to a television director, who sees him as a perfect ticket to higher ratings.

If Hitler were alive today, what would he say on TV? The students imagined him appearing on a popular program featuring new comedians, where he declares: “I promise the German people unprecedented prosperity and lives of satisfaction.” He notes that in order to achieve prosperity, it will be essential to look after the younger generation—the people upon whose shoulders the country’s future will rest. “I will cut tuition and improve the scholarship system,” he says. “And I will double the number of childcare facilities in five years, eliminating the waiting lists for admission.” He also notes, “The government is wasting our taxes by using them not for the German people but for slothful foreign nations.”

People watching this mysterious man on TV admire him as someone who is not just a comedian but who gives voice to their sentiments. Endō Masataka, the third-year undergraduate who wrote the script, explains his thinking: If the real Hitler made a comeback, he would not start out by loudly setting forth his far-right ideology. Rather, he would win people’s hearts by presenting more readily acceptable populist notions.

The waste of taxpayers’ money to which Hitler refers in the play would have resonated in the ears of today’s Germans, who feel that their country is being forced to pay large amounts to support the rest of the EU. As Endō notes, though, “Germany’s contributions to the EU budget are about the same share of its gross domestic product as those of other member countries. But people look at the amounts and think that Germany alone is bearing a heavy load. What’s scary about populism is that it presents easy answers based on simplistic thinking—and that people are quick to accept these conclusions.”

A Soft-Spoken Leading Actor

The TUFS students majoring in German began working on the play in the spring of 2018. Eight works had been proposed, including Schindler’s List and The Reader, but a majority of the students voted for Look Who’s Back.

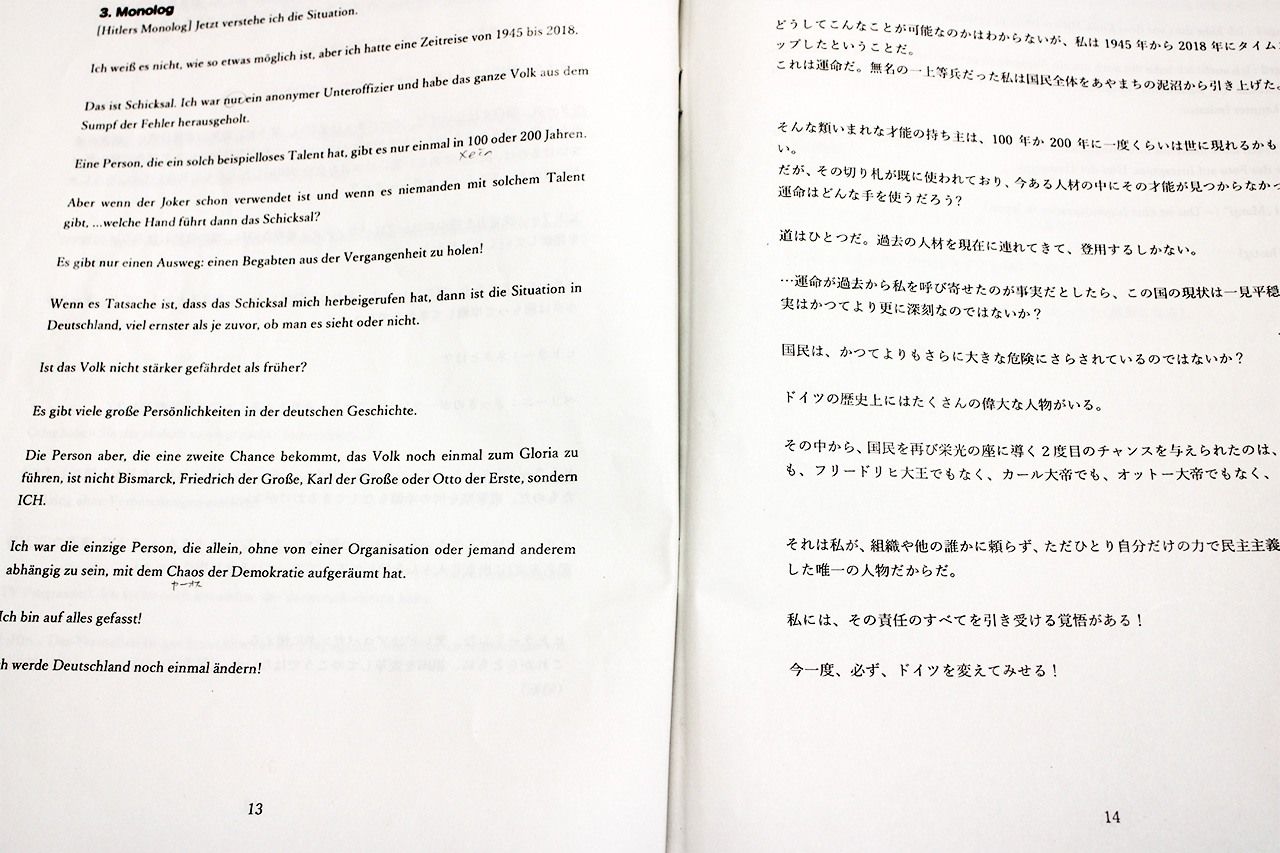

A spread from the script of the play accompanied by a Japanese translation.

Satō says that ever since he started studying at TUFS he had been eager to play the lead in the Gaigosai German drama, whatever it might be. But he was dumbstruck when he learned that the lead character was going to be Hitler. In the play, Hitler delivers a long speech in two parts that together take almost 30 minutes. Satō could not declaim his lines loudly in his residence, so he learned his part by finding empty classrooms at the university and practicing there. And he watched clips of Hitler’s actual speeches to master his delivery of the Nazi salute and other gestures. He is a pleasant, soft-spoken young man in real life, but on the stage he transformed himself into an entirely different character—a screaming, gasping tyrant.

The mothers and children who appeared in the play also performed key roles in showing how ordinary people could gradually become attracted to Hitler. Satō explains, “The purpose was to get the audience to realize that they might have the same reaction.”

Endō, who was responsible for the contents of Hitler’s speech in the play, had an unforgettable shock when he spent a short period studying in a program at the Paris Institute of Political Studies. He knew about “Brexit,” the coinage referring to Britain’s prospective exit from the EU, but in France he encountered the term “Frexit,” the French equivalent. The fact that even in France the idea of breaking away from the EU was being raised gave him the sense of the centrifugal force tugging at Europe as a whole.

Unwillingness to Accept Discomfort

Endō comments on how the Nazis operated. They set forth positions that sounded correct to many people and gained wide acceptance. Then, once they had won power in a democratic election, they used this mandate as the basis for implementing all sorts of measures on their own agenda. In the play, Hitler similarly gains wide acceptance for the positions he propagates on TV and via social media, and this leads him to think of entering politics. When he does, his campaign speech is clearly different from what he had been saying as a comedian on TV; he spouts a more extreme line.

During the decades of the US-Soviet Cold War that followed World War II, Germany was split between east and west, and its voice in the international community was small by comparison with its contributions to the United Nations. In this and other ways, the country was forced to atone for its Nazi past and could not do as it wished. The returned Hitler reveals his rage at this and concludes his speech with this call: “We just have to use the German people’s money for the German people! We’ll leave the EU, bring back the strong mark as our currency, limit immigration, and restore jobs for Germans! We’ll also drop out of NATO and defend ourselves!”

On the stage, Hitler’s receptive listeners are aroused and respond to his speech with a frenzied call of “Heil Hitler!” At this, the audience turned completely silent, and the auditorium was filled with palpable tension. A child started crying, perhaps out of fear. We can assume that the contemporary Japanese watching the play did not know how to respond to Hitler’s return and were trying to keep their distance from what was happening on the stage.

Germany serves as the linchpin of the EU, but sentiment has emerged in favor of abandoning this role. The nation, after earning the trust of its European neighbors through decades of collaboration, has tired of bailing out countries like Greece and taking in refugees from places like Syria. Symptomatic of Germany’s EU fatigue is the erosion of support for Angela Merkel, the long-serving chancellor who has been seen as the EU’s guardian angel; though she still heads the government, she has given up the leadership of her party, the Christian Democratic Union.

Meanwhile, the Trump administration in the United States is conducting a fierce trade war with China, slapping punitive tariffs on imports from that country in order, it claims, to protect the American economy.

Satō declares that there are many matters in the world that require people to accept discomfort, such as the admission of refugees and the maintenance of free trade. “By sharing burdens and being prepared to make some concessions, we ought to be able to build a world of greater overall equality,” he says. “But now, seventy years after World War II, this capacity has been lost, and we seem to be heading almost backwards, as seen in people’s unrestrained expression of their complaints and dissatisfactions.”

The Internet allows ideas to spread like wildfire. If a tyrant insidiously tries to pull the nation in a vile direction, will we be able to put on the brakes at some point? Endō notes, “A frog that jumps into hot water will immediately jump out, but if the water is tepid at first and the temperature rises gradually, it will stay and get overheated.” He is pointing out the danger that we could find ourselves once again on the wrong path before we even notice.

(Originally published in Japanese on May 6, 2019. Reporting and text by Mochida Jōji of Nippon.com.Banner photo: TUFS students perform in their production of Look Who’s Back in autumn 2018.)