Viewing the US-China Trade Conflict as Economic War

Economy Politics World Society- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

From a Trade War to an Economic War

Trade imbalances between the United States and China will not be solved by raising tariffs or through currency manipulation. To cite one example, China uses its high savings rate to invest and then exports the resulting products. Given its excessively high consumption rate, this naturally turns into a trade deficit for the United States.

While the Japanese media is calling US-China trade friction a trade war, from my perspective this has developed into an all-out economic war encompassing technology. Steve Bannon, the former White House chief strategist who was close to President Donald Trump, has stated, “It’s not a trade war, it’s an economic war.” We have not heard the term “economic war” since President Ronald Reagan used it against the former Soviet Union. At that time it led to the Soviet collapse.

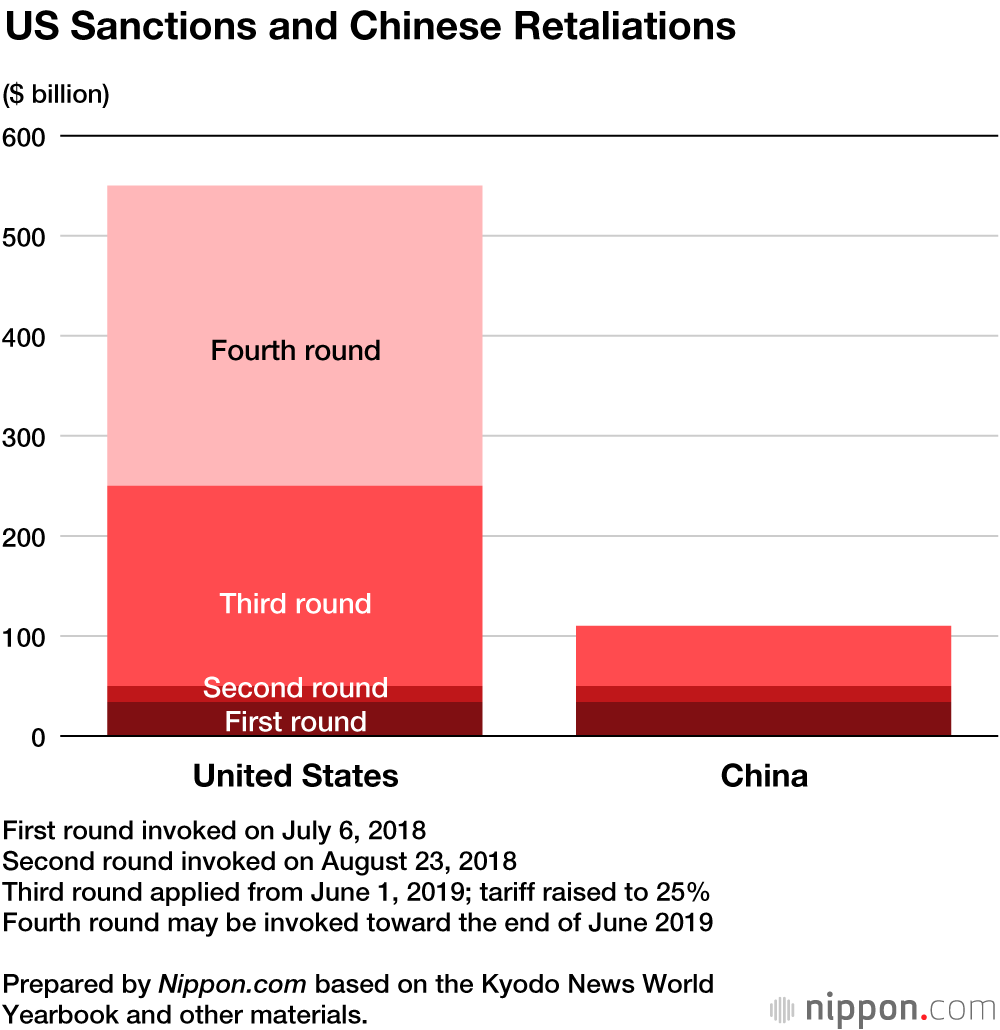

Stock prices rose up until Japan’s extended Golden Week holidays (April 27 to May 6) on sentiment that an agreement between the United States and China was near. These expectations were based on trade negotiations about to take place in Washington DC. However, on May 6, the final day of the extended holidays, President Trump suddenly tweeted that, as a third sanction measure, he would place a 25% tariff on $200 billion of Chinese imports, which brought negotiations to an end.

As the US negotiating team made clear, China wanted to renegotiate issues that it had already committed to, which the Trump administration viewed as China trying to buy time. President Trump’s move was based on concerns that, should trade disagreements worsen while China stalled, falling stock prices would work to his disadvantage in the 2020 presidential election. Therefore, to prevent China from stalling, the United States suddenly increased tariffs on $200 billion in goods.

After promising to end subsidies, to protect intellectual property, and not to steal or demand the transfer of technology, China retracted its promises and has sought to renegotiate since signing the trade agreement would be akin to economic suicide. For example, China’s state-run enterprises are not sustainable without subsidies. It is the same story for intellectual property and technology. If China agreed to US demands, the Communist Party administration itself might not be sustainable.

Where the Game of Chicken Is Heading

In its response, the United States began to prepare a fourth round of sanctions: tariffs of 25% on some $300 billion worth of Chinese goods. These sanctions will have more than a short-term impact. They will become pressure to change a global supply chain revolving around China as the production platform. Many companies are waiting to see whether this $300 billion measure will actually be implemented. If the United States does go forward, these companies will be forced to modify their production systems. Some observers believe that the United States will not make such a foolish move given the cost of relocating factories in China. As a result, Japanese companies are taking their time in deciding what to do. If President Trump is reelected next year, they will likely begin to act.

Should the United States implement a fourth round of sanctions on $300 billion of Chinese goods, China will not have effective ways to retaliate. Selling the US Treasuries it holds would be an act of self-destruction. This would create massive turmoil in international financial markets, and the United States could respond by suspending dollar settlements by China’s state-owned banks. In addition, China would not be able to weaken the yuan. Doing so would spark a huge wave of capital flight by wealthy Chinese, a development China could not withstand.

The key question is whether President Trump and Chinese President Xi Jinping will be able to reach some sort of agreement during the G20 Summit that will be held in Osaka from June 28.

China’s Choices

While the Trump administration wants China to become a free market economy, China has an entirely different economic structure. Should China sign a trade agreement with the United States and implement the agreement as signed, it would be exaggerating to say that the Chinese economy would self-destruct, but it would slow considerably. Depending on developments, the Communist Party administration might fall. There are reasons why the Xi administration cannot simply accept US demands.

However, should China not sign an agreement and stall for time, this would be like waiting in place for certain death. As seen in the Huawei affair, even China’s leading IT companies would be punished and shut out of international society. Huawei can no longer make its products since Google has prohibited the use of its software and since Japanese companies have stopped supplying it with chips. European, US, and Japanese mobile carriers have stopped selling Huawei smartphones, and its global market share has plunged from 15% to 5%.

China is not in a position to accept US demands. Instead, President Xi appears to be stalling for time and waiting for President Trump’s departure. In doing this, though, he is merely sitting on his hands while a killing blow approaches. Huawei’s lifeline has been severed. While the company may survive in China, its role as an international player is likely finished.

The Hegemony of a Data Economy

The historical record shows that wars were fought over territory up to the nineteenth century and over resources in the twentieth century. In the twenty-first century, the nations that control data will be the winners. Once it became evident that data was the most important resource, China plotted to develop companies like Huawei to dominate 5G, the fifth-generation communications standard, and thereby extend its control over everything. The United States, however, saw through China’s plan.

Japan is a manufacturing nation, but more and more people are coming to understand the importance of data. Companies like T-Point sell data. Value is created by analyzing what is selling. Simple manufacturing does not generate much added value. With data, it becomes possible to anticipate future demand. What distinguishes today from past periods is speed, and it is data that facilitates speed. It will not be possible to keep up by simply making things without understanding what data will produce. China looked 5 to 10 years into the future with a sense of urgency, but it was blocked by the United States. The United States also shares this sense of urgency.

Naturally, an economic war with China will be painful for the United States. For example, companies that sell Huawei smartphones and companies that supply Huawei with semiconductor components will be hurt. Such pain, however, will be short term. With the passage of time, changes will made to the global supply chain. This is what is most significant about the US-China trade war. The aim of the economic war declared by Bannon is more about eliminating high-tech companies like Huawei than correcting trade imbalances.

If Trump is not reelected, this dream will not be realized. There is, however, more than a small chance that he will retain his White House spot. In the medium and long term, new supply chains will form that exclude China. Companies with the potential of taking the place of Huawei will be Japanese, South Korean, and Taiwanese firms. Even if there is short-term pain, over longer run, companies that can see opportunities in crises will be the winners. Japanese companies have nothing to fear. They will need to rethink their global strategies and be ready to grasp the chances that appear.

(Originally published in Japanese on June 10, 2019. Translated from an interview by Mochida Jōji of Nippon.com.)