Large-Scale Condominium Renovation: Collusion and High Costs

Architecture Society- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

A Sham Tender

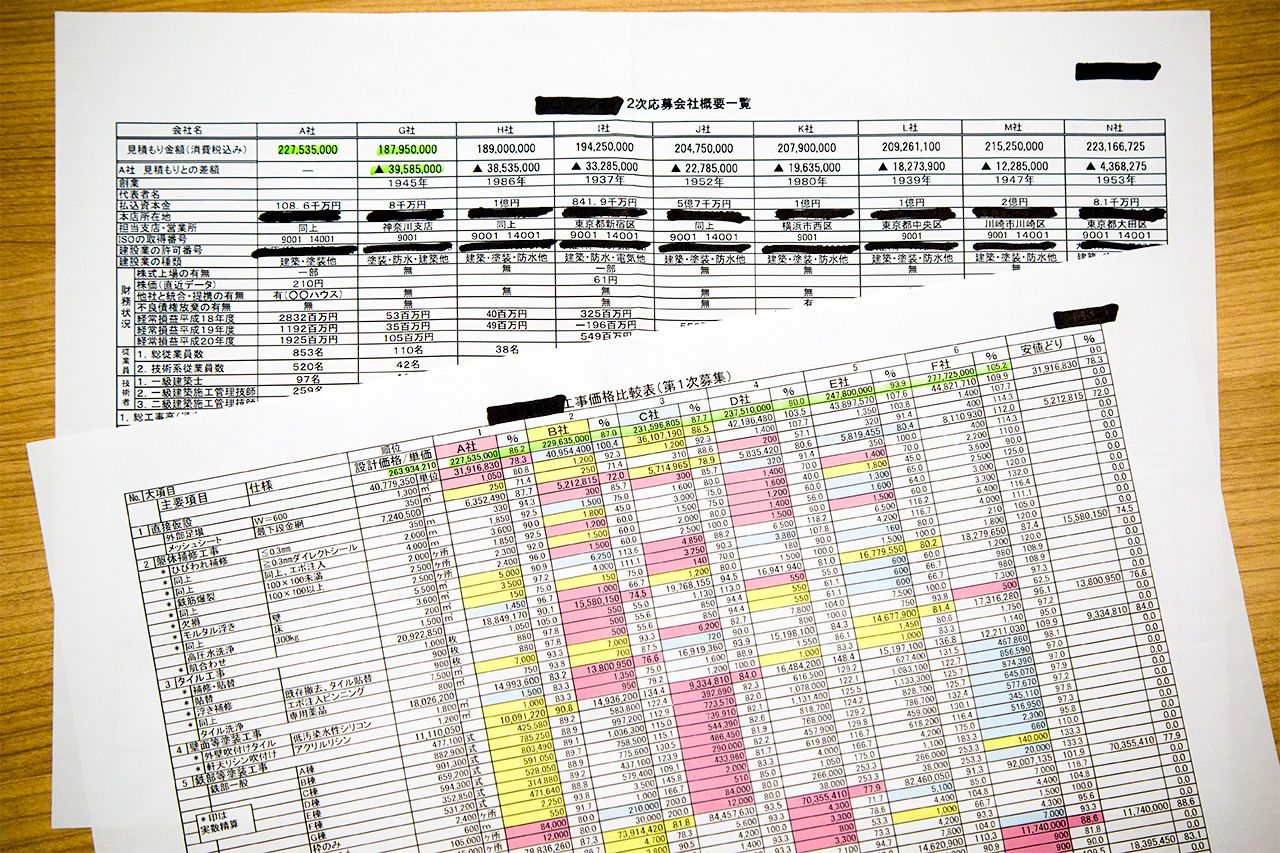

“Well, this is odd,” thought Shigematsu Hideshi as he stared at the one-page list of building contractors who had bid on a large-scale external and waterproofing project on his condominium building, in Kanagawa Prefecture, in 2013. An engineering firm contracted by the condominium management company had conducted the vendor selection process, which involved six building companies. Five submitted similar quotes, ranging from ¥227.5 million to ¥247.8 million. One company stood out due to its higher price of ¥277.7 million. The companies had submitted quotes in response to an advertisement placed in an industry newspaper by the engineering firm, with no apparent anomalies in competitive terms.

But Shigematsu—who holds a nationally recognized certification in condominium management and serves as an advisor to the management association representing residents—was better informed. Somewhat suspicious, he consulted with industry experts, discovering that the same engineering firm, and the same six contractors, often bid for the same projects. In industry terms, this hinted at collusion. He annulled the tender and sought new bids without the involvement of the engineering firm, gaining eight new quotes. The successful company’s bid was ¥188.0 million, almost ¥40 million less than the lowest bid in the initial, sham tender. Even after his remuneration was deducted, it still provided a significant saving for the residents.

Results of the initial tender for condominium renovations and the re-run.

One question remained unanswered. For the building companies to have colluded, they would have required certain data—the budget prepared by the engineering firm. According to those familiar with the process, it indicates a maximum bid price, allowing vendors to secure contracts with a high bid without attracting suspicion. It was obvious that the budget had been leaked to the builders by the engineering outfit.

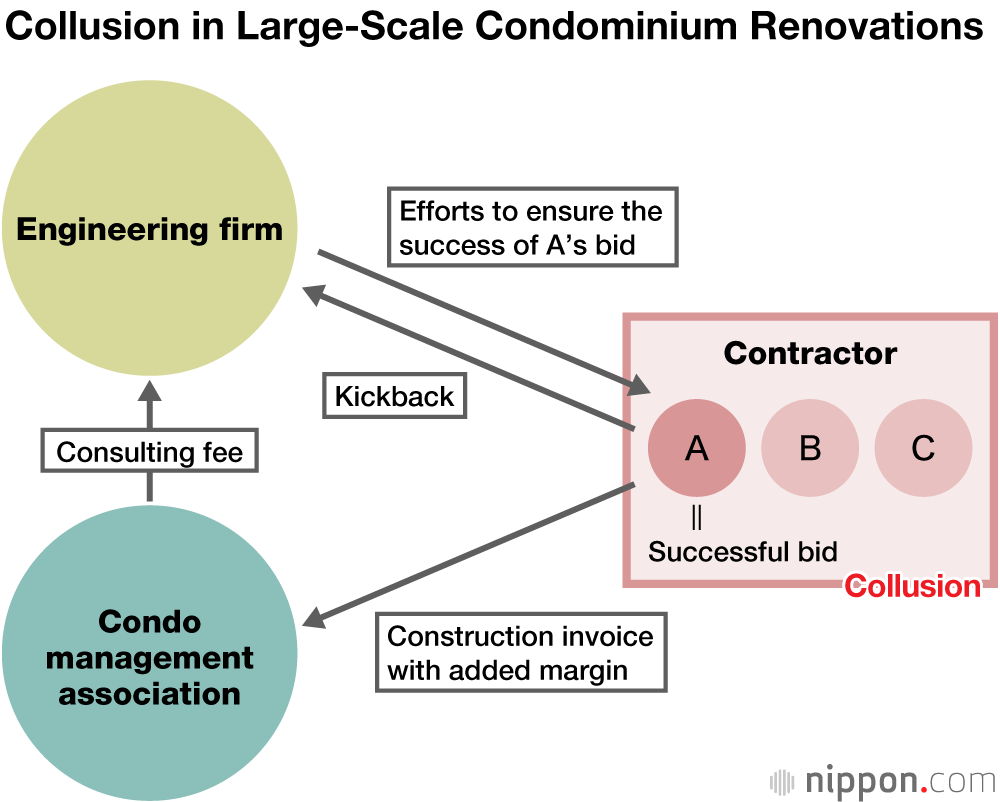

Kickbacks in a Crooked Environment

The normal role of an engineering firm is to supervise the building company on behalf of residents. What would motivate this company to betray the residents and side with the builders instead of encouraging competition among them? The answer became clearer in November 2016, when a member of the condominium’s association handling the rebuilding project lodged a report that certain consultants, hailing from engineering and management companies, were receiving kickbacks from contractors.

The accusation suggested that this raised construction costs, caused financial harm to management associations, and resulted in lax supervision of building companies who fed payments back to consultants, sometimes to the detriment of work quality.

Shibata Yukio, chairman of the Clean Consultant Union, a group of independent engineering firms seeking to clean up the industry, explained that building companies charged higher prices for their work to secure a margin for the engineering firms that required this. By paying a margin, these companies win contracts without spending on their sales activities. The system is fixed so that the builders return excess profit to the engineering firms that assign the work.

The Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport, and Tourism was shocked by the revelation, and held multiple hearings with industry representatives. On January 27, 2017, it released a statement recognizing the existence of consultancies whose interests conflicted with those of management associations. The ministry raised the alarm, citing examples of problematic conduct, including unscrupulous arrangements that enabled construction companies to secure contracts through kickbacks.

Excessive Competition

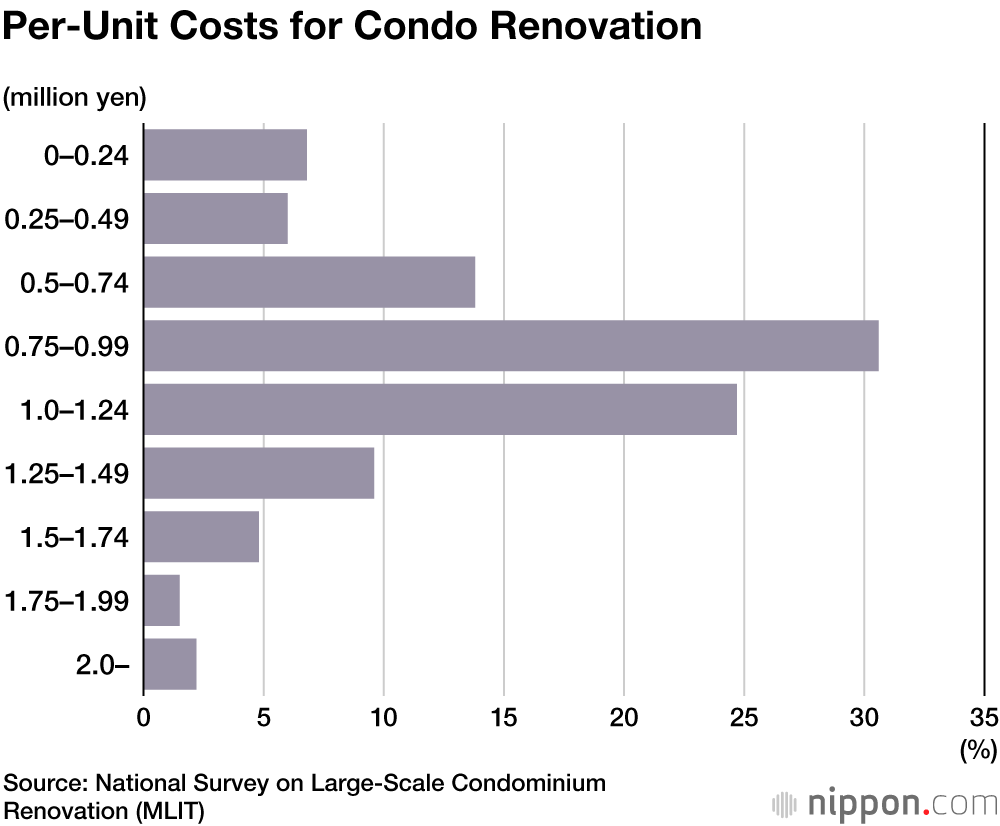

One root cause of the kickbacks is the fierce competition in the construction industry. Around the year 2000, there was a rush of high-rise condominium construction. These housing facilities are now due for their first round of large-scale renovations, which can run up to some ¥1 billion per building. The growth in this work has sparked fierce rivalries among engineering companies. Shibata explains that firms offer consultancy at extremely low fees, and some even resort to coercion to secure contracts. The low consultancy fees initially appeal to residents, but the engineering firms then expect building companies to reimburse them, leading to higher construction costs.

Those close to the industry suggest that kickbacks can amount to around 10% of construction costs. In the case of condominium tower contracts in the billion yen range, margins are up to ¥100 million, which jacks up costs.

Despite the specter of collusion between engineering and building firms in large-scale renovation contracting, the Japan Fair Trade Commission hasnot imposed sanctions or penalties upon any operators. Although collusion is considered a violation of the Antimonopoly Act (as unreasonable restraint of trade), Matsuda Hiromi, an attorney well-acquainted with issues relating to condominiums, notes that it is difficult to prove that meetings took place and who attended. Furthermore, he suggests that, with tax-funded public works, although the JFTC could exercise its investigative powers in an effort to establish collusion, investigations into the private sector are probably a low priority.

Three years have now passed since the alarm was first raised. Shibata says that the situation is actually worsening rather than improving, while the authorities stand by idly. Increasingly covert and organized means are being employed. There have been reports, for example, of firms operating dummy companies to provide an alternative route for handling money, making it harder to identify kickback payments.

Self-Protection Measures

Shūgō Jūtaku Center, a nonprofit organization that supports management associations, reports an increase in claims that these associations are proposing unreasonably steep, and in some cases illegal, hikes in the level of residents’ contributions for building repairs. Kawakami Yasuhisa, chairman of NJK, an NPO for condominium management associations, identifies the risk in associations readily entrusting large-scale renovation work to engineering and building companies simply because they have an existing relationship with them.

Although it can be beneficial to change vendors from time to time to safeguard against overpricing, it also takes a great deal of effort. Management associations, whose leaderships tend to rotate roughly every two years, tend to defer major decisions, and efforts to make fundamental changes to the way buildings are managed can attract opposition from residents. Shibata advises residents looking for change to form a group rather than attempting to act alone.

Given the complicated nature of the industry and lack of transparency, management associations, by nature composed of laypersons, face great difficulty in selecting a scrupulous engineering firm to handle periodic renovations. The attorney Matsuda suggests that selecting a firm based on low consulting fees can be a trap. Kawakami advises that residents need not waste precious time on selecting vendors, as his organization, NJK, can recommend reputable independent companies. NJK is an independent nonprofit that does not receive financial support from specific companies, and Kawakami himself was formerly a journalist at a city desk of a newspaper. He has acquaintances in many fields, providing him with abundant information sources.

In recent years, a growing number of condominium residents are aging and are living on their pensions. Expensive renovation contributions and management fees can place a heavy burden on such people just when they have repaid their mortgage and believe they have settled down for life. Elderly people who lack both money and information cannot afford to squander their money. Nor can they afford to lose their valuable savings in a scam. On this point, Kawakami is emphatic.

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: Condominium towers standing in Musashi Kosugi, Kawasaki, Kanagawa Prefecture. © Jiji.)