Why Are Japanese Youth Distancing Themselves from Social Activism?

Politics Society Lifestyle- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Low Awareness of Social Change

In recent years, youth-centered protest movements have made headlines globally, including the “Fridays For Future” global climate strike movement started by Greta Thunberg, and the “Black Lives Matter” movement that began in the United States in protest against systemic racism.

Japan is no exception: The Global Climate March attracted junior and senior high school students, and high school students converged upon the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology to protest the National Center Test for University Admissions. Japanese people also protested the Public Prosecutor’s Office Act, and participated in online activism including the #MeToo movement for women’s rights, and Japan’s #KuToo movement against workplaces that compel women to wear high-heeled shoes—named for a play on the words kutsu, meaning shoes, and kutsū, or pain.

Despite this, surveys all show that youth political participation, that is, interest or motivation in social movements, is lower in Japan than in other countries.

For example, only 20% of Japanese youth believe they can change their country or society, the lowest among countries surveyed in the Nippon Foundation’s Awareness Survey of 18-Year-Olds, conducted in nine countries, including Japan, China, South Korea, the United States, and Britain. According to the sociologist Hamada Kunisuke, the 2015 Comprehensive Survey of Social Inequality in Contemporary Japan saw ranked Japan’s youth lowest among the seven advanced nations surveyed regarding belief that their participation could influence social phenomena.

This perception is not limited to people in their teens or twenties. A survey by public broadcaster NHK showed faith that public action could influence national politics was highest among those born from 1949 to 1953, with the level dropping as the age of respondees fell. Essentially, Japanese disenchantment with politics and social movements is not limited to youth.

This trend among youth is not the result of their nature or moral fiber. Rather, there are structural and cultural factors that impact on their consciousness, pushing youth to distance themselves from politics. Based on various survey data, this essay examines youth impressions of social movements, and the reasons why youth avoid or are antipathetic towards activism.

Negativity Toward Protests Stronger Among the Young

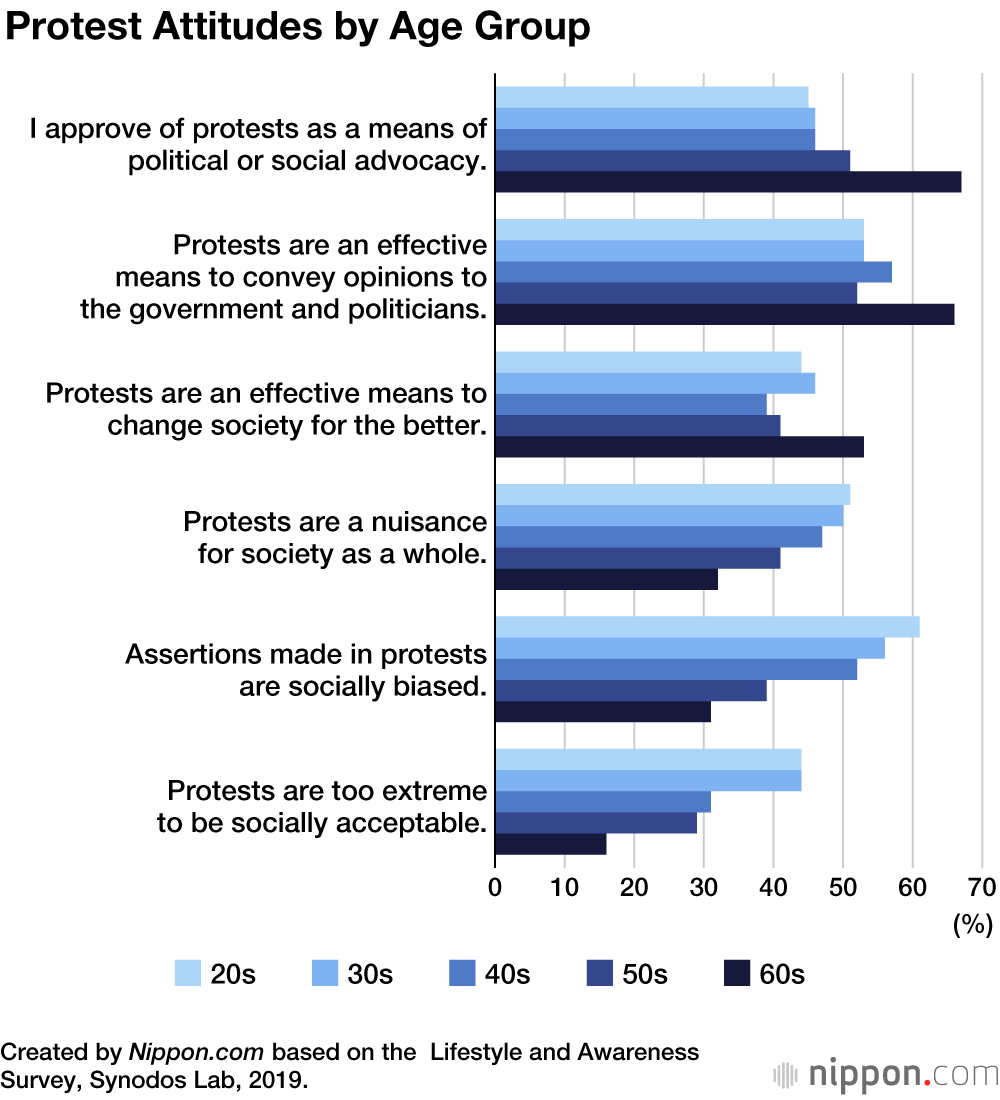

How are younger generations specifically distancing themselves from politics and forsaking social movements? In 2019, I was part of a team conducting a survey through Synodos Lab, a group that researches international social trends. The sociological survey asked people aged from 20 to 69 about their attitudes toward social movements.

The survey gave six positions towards activism, using protests as the example. The chart below reflects the level of agreement or disagreement with each question for the different age groups. The first three questions asked the degree of approval respondents had toward protests, while the latter three asked about negative attitudes.

Responses varied significantly between the age groups, but a key trend was the negative impression of protest among younger generations. In contrast, older generations expressed a comparatively positive impression of protest.

Economic Factors Inhibiting Political Development

Why do young people feel that protests are a nuisance, are socially biased, or are extreme? One factor is the reduced visibility of social movements in Japan since the 1970s. Labor unions are seeing a fall in membership rates, and the political scientist Kinoshita Chigaya notes that, at universities, student groups including councils and clubs are also in decline. Japan has also seen a drop in the number of protests held in cities since the 1970s, and labor and civil movements are therefore becoming less visible for ordinary people. In such circumstances, it is difficult for young people to perceive ways to criticize or oppose society. They could better comprehend them if they witnessed transformation brought about by social activism, but if these groups are not visible, it is difficult to commit to them. In today’s society, it is very understandable that they have trouble believing that their actions could change anything.

Socioeconomic conditions have also changed dramatically. University fees, for example, have risen steeply since the 1970s. Although not all youth attend university, even university students, a comparatively affluent stratum, are facing more severe time and monetary poverty compared with past generations. A survey conducted in 2016 by the Japan Student Services Organization indicated that reliance on student loans among daytime university students more than doubled in recent decades, from 22% in 1992 to 49% in 2016. Students face greater burdens in the form of fees and loans, which places more pressure upon them in job hunting. Consequently, it is not easy to advocate a political position or to take a stand against those in power.

Increasingly Fluid Employment and Social Status

In Minna no wagamama nyūmon (Introduction to Everybody’s Selfishness), I describe how, in addition to changes in social circumstances, increased individualism and fluidization (the increase of nonregular employment) are also driving youth away from politics. In his book Nihon shakai no shikumi (The Structure of Japanese Society), the historical sociologist Oguma Eiji argues that although Japan was not entirely homogeneous in the 1970s or 1980s, there were clear life “paths” that existed, according to distinct attributes or categories, such as youth, women, and workers. In contemporary society, though, he believes it is rarely possible to identify a category of homogeneous “youth” either in the classroom or the workplace. This creates uncertainty: It becomes hard to raise one’s voice to defend one’s interests when it is not clear how many others share those interests.

Meanwhile, the illusion that “we are all the same” is growing in schools, workplaces, and other settings. Consequently, people fear that openly voicing their opinions may invite unwanted consequences, making others see them as troublesome, or prejudiced, and causing fallouts with colleagues.

Fluidization of employment and social status also have an impact. Casual workers now make up nearly 40% of the workforce, and work styles are diversifying, which limits people from participating in sustained action, whether related to labor or social issues. Even if activism achieves a successful outcome, it is hard to know how long one could enjoy the benefits. Such transitory circumstances cause youth and others in fluid positions to psychologically distance themselves from efforts to change society.

The decline in youth political engagement is not just an issue for young people—it affects all of us. Adults need to take the initiative, raising their voices in protest against unacceptable policies and systems, to help reduce the distance between youth and politics. It is important to demonstrate that expressing objection to governments is respectable, and that we can change society through our own actions. We should not forget that, even with diversifying values, along with increased individualism and fluidity, we can help many other people if we are willing to stand up in support.

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: A February 21, 201,6 protest in Shibuya, Tokyo, coordinated by the high school student group T-nsSOWL against national security legislation. © Jiji.)