Lessons from Yūbari’s Medical System for the COVID Era

Economy Society Health- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

A Breakthrough Shift to Primary Care

The current COVID-19 pandemic has raised fears of a collapse of the medical system, an issue frequently discussed in the media. I was researching the topic long before the current crisis, since my time as director of the Yūbari City Clinic shortly after the Hokkaidō municipality’s financial collapse, when the media was awash with such stories.

There are significant differences between the present pandemic threat and the collapse of Yūbari’s medical system. What I learned from listening to patients in Yūbari and from reviewing data from Japan and other countries suggests that the current debate ignores significant cultural elements, including differing views on life and death and independent life choices.

Yūbari’s medical system changed radically as a result of the bankruptcy. The city could no longer afford to maintain its 171-bed municipal general hospital, the only such facility, which was forced to downsize to a 19-bed clinic. Yūbari had Japan’s oldest average population, yet it took the extraordinary move of a 90% reduction in terms of bed numbers alone. The clinic’s first director, and my mentor, Murakami Tomohiko, addressed the fiscal squeeze through a shift in focus to primary care, which had not been a medical focus previously in the city. Primary care offers initial consultation and diagnosis for patients, only referring them to specialized medical facilities if required. The approach is similar to a family doctor who keeps watch over people’s health, including by offering lifestyle and illness-prevention advice.

Patients requiring surgery or specialized treatment were quickly transferred to hospitals farther away. The majority of elderly patients, meanwhile, who suffered from chronic illnesses or general conditions related to aging, saw the introduction of home care, nurse visitations, and other services to provide care outside of the hospital system. It was certainly not an abandonment of high-level care. Nor was it simply forcing home treatment upon patients who could not secure one of the clinic’s 19 beds. During my time at the clinic, there was not a single occasion when all 19 beds were full.

A Peaceful Death Surrounded by Alcohol

Elderly people typically develop weaker legs and backs. Some of them develop memory loss, while others lose the strength to swallow effectively, a condition that can lead to repeated bouts of pneumonia. Unfortunately, for many such elderly patients, their chronic conditions cannot be treated medically. The bigger question is how such people would like to spend the last years of their lives. Would they prefer to stay placidly in a hospital receiving care, or to live as they please in the privacy of their own homes? An individual should be free to make such decisions, and medical practitioners should not make judgments based simply on a so-called medically correct approach.

I recall an alcoholic patient in his nineties in Yūbari. His liver and lungs were a mess, and his health was extremely poor, yet he drank heavily at home all day. Previously, he attended outpatient services, putting on a respectable front in the examining room.

But after we switched to home care, I visited his home and saw for myself his room strewn with shōchū bottles. From a medical perspective, of course, this is unacceptable. Prior to Yūbari’s financial and medical collapse, any doctor would have insisted that the man quit drinking and be immediately admitted for treatment. A polite patient would acquiesce to their doctor’s orders. He would be hospitalized and quit drinking. This is the “medically correct” solution—but it overlooks personal lifestyle choices and the question of trust between the doctor and patient.

This old man was adamant: “Why on earth should I quit drinking? I’m over ninety—of course a check-up will uncover something. I don’t want my blood taken. I won’t go into hospital. Do you think if I quit drinking, got tested, and went to the hospital I’d be right as rain? Run the 100-meter dash? If this were the case, I’d be there! But I won’t quit and I’m not going anywhere. I’m staying here until I die.”

He stayed in his home, kept drinking, and died in peace.

He was not the only one. When I sat together with patients and we talked frankly, many of them told me that they would prefer to spend their final days unrestrained at home than under the authority of a hospital. In such cases, all that is required is proper implementation of home care, nurse visitations, and in-home nursing care. And this became the focus of our efforts after shifting to a primary-care model.

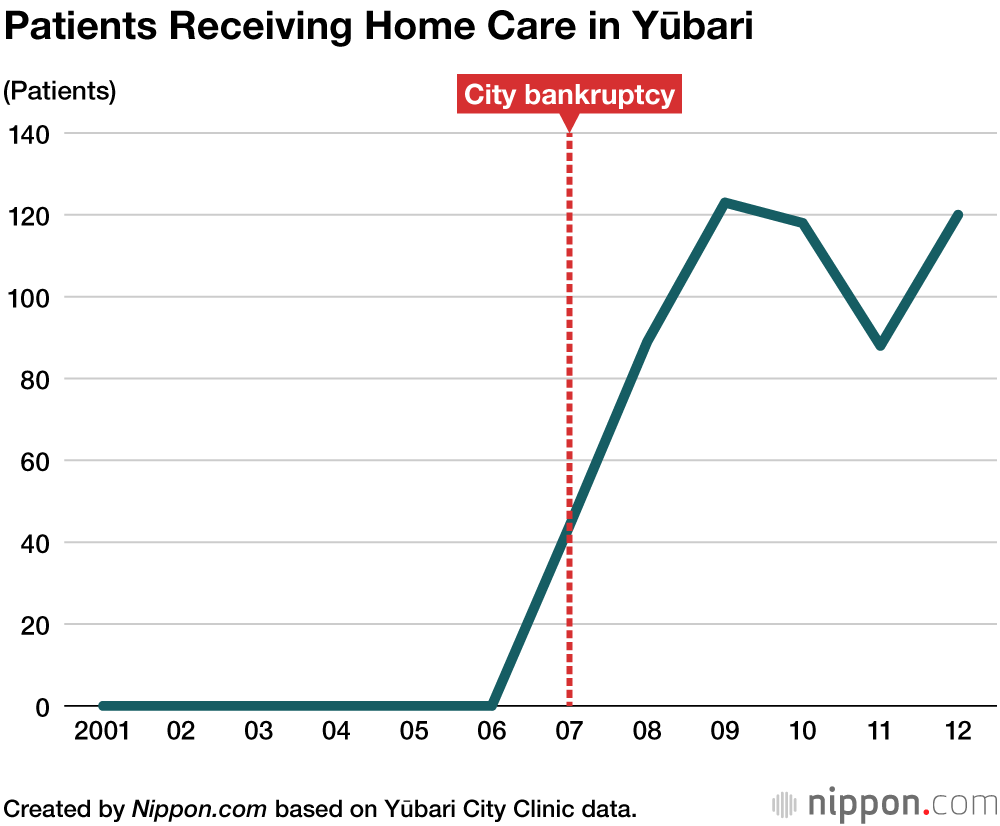

The transformation of the medical system had a tremendous impact. The number of patients receiving home care rose to over 100 and the highest level recorded. As the population ages across Japan, ambulance demand is ever-growing, yet Yūbari saw a surprising opposite. One reason was that patients were able to make their own life choices, such as the 90-year-old man described above. In the end, he chose not to call an ambulance, and his next of kin and the medical staff involved were willing to prioritize his wishes. Of course, annual costs also decreased with this change to medical care.

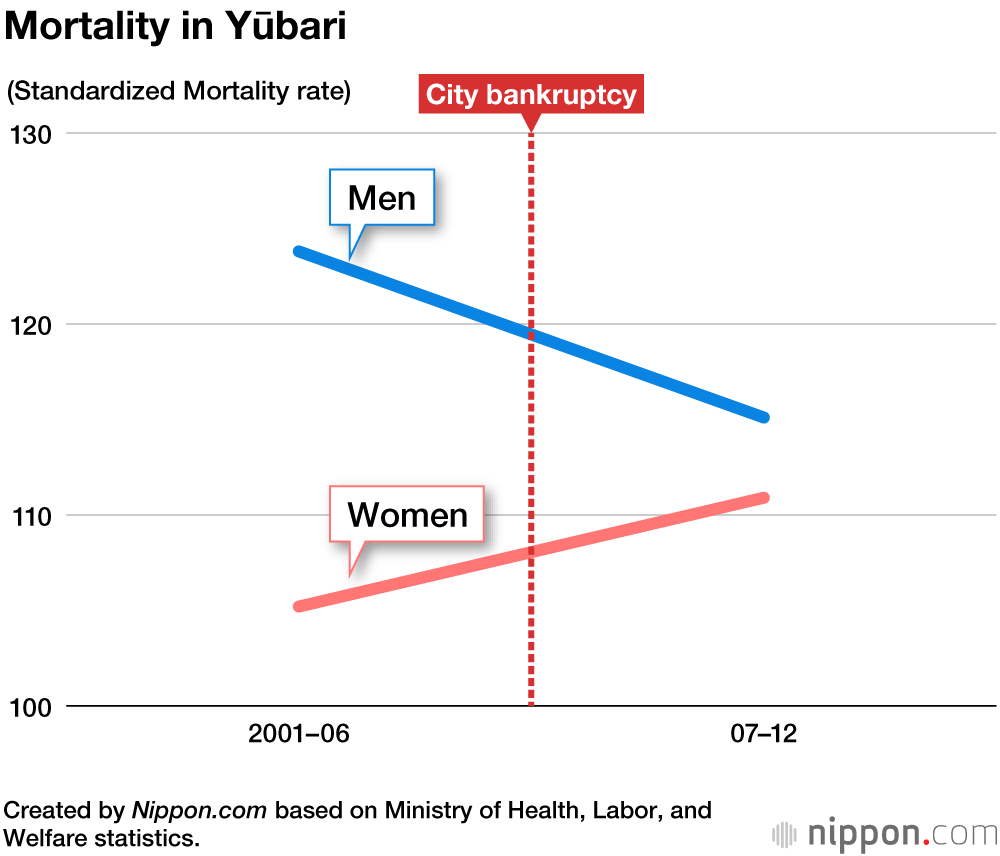

Furthermore, despite being unable to provide specialized care due to decreased bed numbers, the standardized mortality rate across the population did not drastically worsen. Even those of us working in the medical field were very surprised at these outcomes. It suggests that specialized medical care for elderly people does not necessarily improve their health.

Reassessing Aged Care in the Pandemic Era

Now, let us consider the threat of collapse of the medical system in the COVID-19 pandemic. Japan has the world’s highest number of hospital beds per capita: five times more than Western countries. It has also seen COVID-19 infection and mortality rates just one-tenth of those nations. Despite this, Japan’s medical system is said to be on the verge of collapse. This betrays serious problems in the Japanese healthcare system.

Elderly people have accounted for most severe COVID-19 cases and related deaths. There have been no deaths among minors. I wonder whether all of Japan’s elderly COVID-19 patients have received hospital treatment regardless of their wishes. Have they been given the freedom of choice offered to the elderly in Yūbari? Or has priority been placed on a “medically correct” approach, based on their doctor’s decision?

In our crusade for safety and security, elderly people can become trapped like caged birds. This was an issue even before COVID-19, but it has become accentuated during this pandemic. Currently, many elderly patients are under virtual house-arrest: forbidden from stepping outside of their care facility or hospital, or from receiving visitors, in the name of preventing infection.

Of course, we cannot make unequivocal comparisons between a 90-year-old man who dies drinking in his home and elderly patients hospitalized with COVID-19. The latter pose an infection risk, and if they live with family, no doubt need to be treated in hospitals. But if we look at medical care provided for the elderly, there are some common themes.

The medical situation faced in Yūbari saw successful outcomes, including a halving of ambulance calls. The cut in bed numbers from the financial failure was the impetus for providing patients with the opportunity to make their own choices, often leading to them choosing to live their final years in greater contentment, and reducing emergency calls. I earnestly hope that the rare opportunity created by this pandemic stimulates greater momentum to reconsider how we provide medical care for elderly people in the future.

(Originally written in Japanese. Banner photo: Yūbari City Clinic, Hokkaidō, which was downsized from a municipal general hospital following the city’s financial collapse. Photographed May 13, 2007. © Jiji.)

Hokkaidō financial crisis medical senior citizens coronavirus COVID-19